Needle exchange comes of age

The New Zealand National Needle Exchange Programme was the first of its kind in the world, and this year, it turns 21. Kim Thomas looks at the history of this quiet achiever and talks to some of those who have helped form its development over the years.

Canterbury-based injecting morphine user Neil reckons he’d probably be dead if it wasn’t for New Zealand’s National Needle Exchange Programme (NEP).

“Over the years, the needle exchange has quite literally saved my life. I spent every dollar on the score and didn’t have money for expensive equipment. If the exchange hadn’t been around, I would have just reused old needles or shared with people and probably got AIDS.

“It’s not only saved my life, but it’s probably saved the lives of lots of ordinary people, like kids who find dirty, used gear dumped around the streets.”

Neil, now 41, has been an injecting drug user (IDU) for more than 20 years but has managed to avoid catching HIV and, until recently, hepatitis C (hep C).

As a curious young man, Neil tried heroin while living in Australia and became hooked. With the exception of three or four years when he was clean, Neil has shot up for the past two decades.

Every time, with the exception of a couple of instances in which he believes he contracted hep C, Neil has used equipment he bought from the needle exchange.

“I kick myself about that (not using clean equipment) every day. I know exactly when I would have caught hep C because I was lazy and didn’t have my clean needles.”

Neil is one of thousands of Kiwis whose lives have been affected by our world’s first National Needle Exchange Programme.

From a small Auckland exchange, staffed mostly by volunteers, and a handful of pharmacies around the country, the NEP has grown into a network of 18 dedicated exchanges, more than 175 pharmacies and scores of other outlets including sexual health centres, Prostitutes Collective offices and a mobile van on the West Coast of the South Island.

This year, the NEP celebrates 21 years in operation.

In August 1987, the then Labour government passed a law allowing pharmacies and exchanges to sell needles and syringes.

By August 1988, there were five dedicated exchanges, in Auckland, Christchurch, Palmerston North, Wellington and Dunedin.

In its first years, the NEP sold about 100,000 needles nationwide and now provides IDUs with about 2 million sterile needles and syringes every year.

In 2004, the exchange’s set-up changed slightly so users could get a free needle and syringe in exchange for a used one. Previously, injection equipment was provided on a user-pays basis.

Health experts say the programme is why New Zealand has one of the lowest rates of HIV among IDUs in the world. They say it has helped limit the spread of the virus within drug injecting communities.

Exchanges have also become focal points for providing health and education to the IDU community.

So how did New Zealand become the first country to have a national network of exchanges?

It seems we can thank the fear of AIDS, open-minded politicians and brave people in communities around New Zealand who believed we would all be better off if IDUs had ready access to clean injecting equipment.

In the mid 80s, Auckland-based health and rehabilitation worker Robert Kemp was asked by the Department of Health (now the Ministry of Health) to join a group looking at how to minimise the spread of AIDS.

“At the time, HIV was a big, unknown, scary disease for the population and politicians. There was a sense of crisis and panic; real Armageddon-type projections that AIDS was going to take over the world and millions of people were going to die and contribute to the collapse of civilisation,” Kemp says.

This fear among the general population gave politicians the confidence to do things they would never otherwise have done, such as establishing needle exchanges for drug users, who were seen as ‘dirty’ by many, he says.

New Zealand’s participation in the Ottawa Charter, a multination agreement that promised to improve health in certain quarters of society, particularly among marginalised groups such as homosexuals and drug users, also put momentum behind suggestions for a scheme to sell clean injecting equipment.

Kemp was asked to help set up the first needle exchange in cramped conditions in an office space on Auckland’s Symonds Street in 1988.

It was a chaotic but heady time when Kemp and a largely volunteer workforce felt they were involved in the start of something really special.

“We had no idea what to expect; just that it was very, very important to have needle exchanges in this country. We knew they were unusual times and, in the back of our minds, we knew we were involved in ground-breaking stuff, but mostly we just got on trying to make a go of it.

“We got money from the government for the premises and a little bit more. We were running on the smell of an oily rag and relied heavily on volunteers, but it was a wonderful time, really special. We got fantastic support from some pretty important people in the Auckland community who joined our board.”

Kemp says there was a slow trickle of users in the first six months or so, but word soon spread, and users started streaming though the doors.

Michael Baker, now a seasoned public health researcher at the University of Otago, was a somewhat naive, young doctor in the late 80s.

Baker joined the Ministry of Health just as the idea of needle exchanges were being mooted and ended up shepherding legislation through Parliament to enable the sale of needles and syringes.

“It was a real eye opener for me entering the world of politics. The machines of government are so powerful and mysterious.”

Baker says the establishment of the Needle Exchange Programme owes a lot to a brave new political environment in the mid to late 80s.

“A new, quite progressive Labour government had been voted in at the time, after years of a National government. There was a very talented bunch of new politicians, and there was a sense that anything was possible.

“Michael Bassett was Health Minister at the time, and I believe he can take credit for a lot of really innovative schemes including the NEP. He encouraged staff to look for innovative ways to address the problem of AIDS and gave us a really long leash to explore different interventions.

“It [championing the establishment of exchanges] was a bold political move and a real leap of faith because there was a lot of fear but not a lot of firm evidence or epidemiological information about AIDS at the time.”

In the year before the Auckland needle exchange was established, the AIDS Advisory Committee, a group of politicians and advisors, met to work out how such a scheme could work.

Baker says the idea of supplying free drug injecting equipment to addicts was unacceptable to many on the committee, and some were not convinced of the idea of an exchange at all.

However, Baker says, after months of debate, “We were lucky logic prevailed and politicians came together to pass the legislation.”

Making the NEP user pays was central to it being voted through Parliament, so the general population would not object to the ‘unseemly’ group of drug users being given free equipment on the taxpayers’ purse.

In 1987, Christchurch pharmacist Dave Pollard, then in his 60s, was selling needles to intravenous drug users visiting his inner-city store. For his trouble, Pollard was dragged before his professional body who gave him a $3,000 fine and a written warning. But neither this, nor being under the watchful eye of Police, deterred him.

“We read a bit about AIDS and had addicts coming in all the time desperate for clean equipment. We realised if we could give them clean needles, it would be good for the community,” Pollard says.

“It was never to make money. It was to help the health of these people. I stood by my decision despite pressure and would have continued to stand by it even if it meant being closed down.

“The authorities warned there would be trouble with addicts coming in for needles, but we had none because we treated them as customers and with respect instead of putting them down.”

Pollard, now retired but still a strident supporter of the NEP, later received a Canterbury Civic Award for his work.

At the time of his disciplinary appearance before the pharmacists’ professional body, scores of Canterbury IDUs offered to help Pollard pay what would have been a hefty fine back then, because they recognised how vital his work was to their health and safety.

Almost everyone Matters of Substance spoke to about how the NEP was established says it would not have happened without the dedication of champions such as Pollard and caring souls who acted as go-betweens for officialdom and the injecting drug taking community.

Other everyday champions whose names came up over and over again during interviews were Gary McGrath and Rodger Wright (who, people say, were both instrumental in getting the exchanges working and have since died of HIV) and pharmacist Maree Jensen (who provided clean equipment to IDUs before it was legal).

NEP National Manager Charles Henderson says pharmacists such as Pollard and Jensen were groundbreaking and enabled politicians to see the scheme had merit.

“These people were able to exemplify how the sky wouldn’t fall in if you made safe injecting equipment available.

“Before the legislation was passed, there were pharmacists willing to stick their necks out and provide needles and syringes. They did it even though it was a criminal act and police kept an eye on them. They were before their time in realising that providing clean needles was a health issue and would help stop the spread of HIV.”

Sociologist Steve Luke spent his last years researching and writing a doctoral thesis on the development of New Zealand’s NEP.

Luke tragically died from injuries sustained in a car accident in late 2008, but his work lives on as some of the best commentary about how New Zealand became the first country in the world to have a national NEP.

Luke himself experimented with injecting drugs and had strong friendships with those in the IDU community.

His master’s thesis was so impressive he was given the opportunity to upgrade it to a doctorate – a rare honour in the academic world reserved for exceptional work.

Like Henderson, Luke’s thesis says the network would not have been possible without people willing to stick their necks out. He particularly credits the involvement of ‘peer professionals’ – such as former or current injecting drug users who acted as buffers between the nervous IDU community and government bodies – with making the programme a success.

One of Luke’s academic supervisors was Canterbury University Sociology Associate Professor Rosemary Du Plessis.

She says Luke’s research found the success of needle exchanges relied on people with relationships in the drug injecting community making the exchange an accessible and friendly place to come to.

This included staffing the exchanges with people who were known to drug users, engendering trust in a population involved in an illegal activity.

While pharmacies were and remain an important part of the NEP, for many drug users, they were not friendly places to visit, Du Plessis says.

“Some pharmacies didn’t like drug users coming into their pharmacies because users are on the margins of society and are often looked down upon by the general public. The presence of users in suburban pharmacies was therefore not ‘a good look’ to the normal clientele.”

Du Plessis says Luke’s thesis highlights the importance of work done by the AIDS Foundation and the IV League, a group focused on empowering IDUs.

“The AIDS Foundation was an incredibly good model for how community networks could work with government to achieve a goal, such as minimising the spread of HIV,” she says.

“Before community-based needle exchanges were set up, the gay community had worked really effectively with government to develop strategies for promoting safe sex and condoms. This groundwork was invaluable to the establishment of needle exchanges, which depended on connections between the IDU community and government to get clean needles and syringes to injecting drug users.”

The establishment and running of the NEP has not been without its hurdles. Henderson, who worked his way up over about a decade from manning the front desk of an exchange to becoming National Manager, says exchanges have always struggled with the ‘not in my back yard’ (NIMBY) factor.

“There’s always been a lot of NIMBY, for sure. Neighbours have petitioned landlords and local councils to have exchanges thrown out and threatened legal action, but it never went anywhere. The exchanges try to keep under the radar, and most people would not even know they were there.”

There have also been successful criminal prosecutions of drug users found with injecting equipment.

Henderson says one of the biggest challenges for the future lies in getting the programme into prisons, where there are high rates of IDUs but no access to clean equipment.

“They are forced to share smuggled equipment. It’s a dire situation. Thank goodness HIV is low, but this is not the case for hep C.”

Addressing the disturbingly high levels of hep C among IDUs is another big challenge, Henderson says, because it affects so many more people than AIDS.

Canterbury Medical Officer of Health and long-time NEP supporter Dr Cheryl Brunton says the spread of hep C has been difficult to control because it was already circulating widely, unbeknownst to health authorities, before the NEP was established.

“The hep C epidemic wasn’t identified until the late 80s. Trying to slow the spread of something that is already widespread is pretty hard.”

Despite high numbers of IDUs getting clean equipment from the exchange, the odds are that sharing the occasional unclean needle will transmit hep C, she says.

“In the early 90s, a survey showed about 60 to 70 percent of IDUs who used the needle exchanges had hep C.

“That means, if you share a needle with someone, you are highly likely to catch it. You are far less likely to get HIV from sharing a needle because only a very small number of people are affected.”

New data is due out soon, and the hope is that numbers have dropped, Brunton says.

If Henderson and his NEP colleagues have anything to do with it, young users will be protected from the threat of disease such as HIV and hep C for many years to come.

“We are happy to take our place in the health sector, and we think we do a lot of good, but we don’t tend to blow our own trumpet. There are lots of organisations out there, such as the Drug Foundation, who lobby well, but we see our priority as providing the best service we can to IDUs. That’s really what we are here for,” he says.

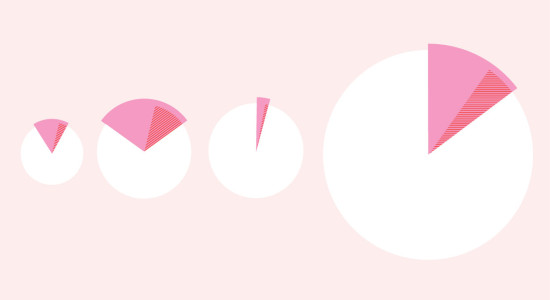

1%

At less than 1%, New Zealand’s HIV prevalence among IDUs is extremely low by world standards. Needle Exchange New Zealand deals with the tough issues of contracting hep C with a widely successful health promotion campaign.78%

Ethnic breakdown of service users: 78% European, 13% Māori, 9% Asian and others.18

There are 18 dedicated peer-based needle exchanges and over 180 pharmacies; 75% of all equipment is distributed through the dedicated exchanges.18

There are 18 dedicated peer-based needle exchanges and over 180 pharmacies; 75% of all equipment is distributed through the dedicated exchanges.2

Million. During 2006, two million ‘sharps’ were distributed under 1-for-1, up from one million during 2002/2003.64%

In 2002, 64% of users had ‘reused a needle’ in the last month, while in 2008, this dropped to 42%.4.1%

In 2002, the reported ‘use of someone else’s needle’ was 6.6%, while in 2008, this had dropped to 4.1%.| Drug | 2002 survey | 2008 survey |

|---|---|---|

| Methadone | 32.3 | 55.1 |

| Morphine/MST | 57.6 | 43.7 |

| Ritalin | 12.3 | 34.6 |

| Speed | 25.6 | 16.3 |

| Methamphetamine | - | 15.7 |

| Homebake | 10.8 | 6.0 |

* Percentages do not add to 100 because many respondents selected more than one answer.

Note that methadone has replaced morphine/MST as the dominant drug injected. This may reflect the ageing of the respondent group and the higher likelihood of them being in methadone treatment and thus with relatively greater access to the drug. The rise of methamphetamine is clear, although it seems to have simply displaced much of what was described as ‘speed’ in 2002. Ritalin injecting, in contrast, appears to have become significantly more common.

Recent news

Reflections from the 2024 UN Commission on Narcotic Drugs

Executive Director Sarah Helm reflects on this year's global drug conference

What can we learn from Australia’s free naloxone scheme?

As harm reduction advocates in Aotearoa push for better naloxone access, we look for lessons across the ditch.

A new approach to reporting on drug data

We've launched a new tool to help you find the latest drug data and changed how we report throughout the year.