About a drug: Heroin

Heroin is probably the most infamous member of the opioid family. Opioids are depressants, not because they make you sad, but because they slow down the activity of the central nervous system and messages sent between the brain and the body. Alcohol, benzodiazepines, GHB and cannabis are also depressant drugs.

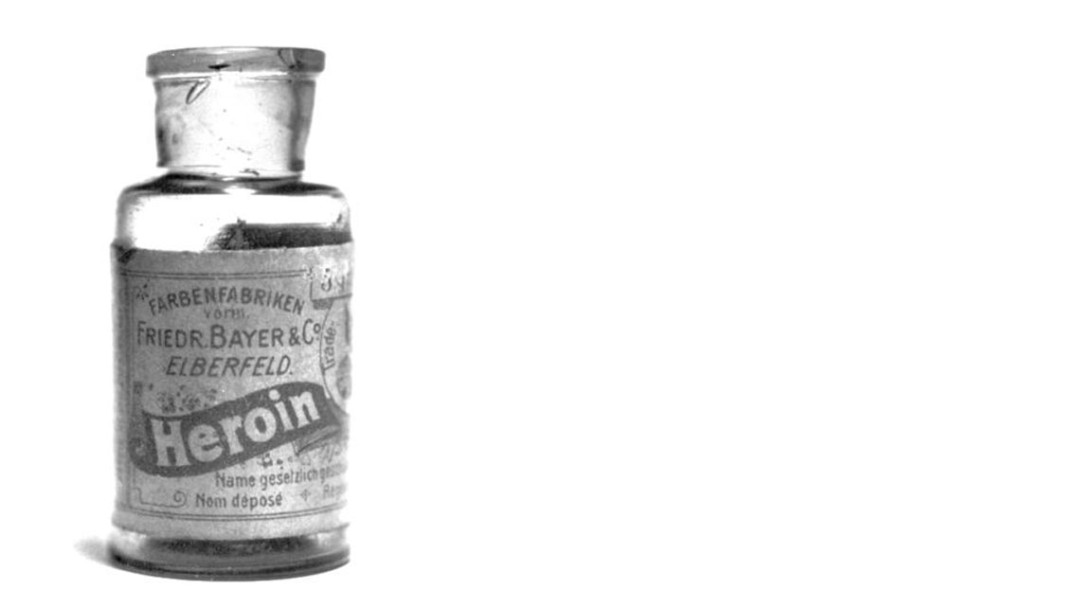

Heroin was first synthesised in 1874 by English chemist C R Alder Wright, was independently re-synthesised 23 years later by German chemist Felix Hoffmann. Hoffmann was trying to produce what we now know as codeine – a substance similar to morphine but less potent and addictive. Instead, he produced a form of morphine that was almost twice as potent.

Bayer was quick to market the new ‘diamorphine’ as a cough suppressant and cure for morphine addiction under the trade name heroin. The discovery that it was, in essence, a quicker-acting form of morphine was embarrassing for Bayer and has gone down in history as one of the company’s biggest blunders.

In 1914, the US passed the Harrison Narcotics Tax Act to control the sale and distribution of heroin and other opioids, restricting its use to medicinal purposes only. It is now a Schedule 1 substance, which makes it illegal for non-medicinal use in signatory nations to the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs treaty.

Today, Afghanistan remains the world’s largest producer of heroin. In 2004, it was producing 87 percent of the world’s supply. However, production in Mexico rose 600 percent between 2007 and 2011, changing that percentage and making Mexico the second-largest producer in the world.

In New Zealand, heroin is classified as a Class A drug under the Misuse of Drugs Act 1975, attracting a maximum term of life imprisonment for importing, manufacturing and/or supplying. Possession carries a six-month imprisonment term and/or $1,000 fine.

Heroin is always referred to as diamorphine when used in medicine, and it is almost always indicated to treat chronic pain. It is supplied in either tablet or injectable form, often in preference to morphine because it has less severe side effects.

While non-medicinal use is almost universally illegal, a number of countries have been experimenting with diamorphine maintenance programmes to treat users who have failed at other withdrawal programmes.

In 1994, Switzerland began such a trial in which it proved superior to other forms of treatment in improving the social and health situation for illicit heroin users. It was also found to save money, despite high treatment expenses, by significantly reducing costs incurred by trials, incarceration, health interventions and crime.

The success of the Swiss trials led Germany, Holland, Denmark and Canada to try out similar programmes.

Some Australian cities (such as Sydney) now have legal, supervised injecting centres, in line with other wider harm minimisation initiatives.

In non-medicinal settings, heroin is used as a recreational drug for the rapid onset of transcendent relaxation and intense euphoria it induces. In the 1996 film Trainspotting, lead character Mark Renton describes its effects as follows: “Take the best orgasm you’ve ever had... multiply it by a thousand, and you’re still nowhere near it.”

The onset of heroin’s effects depends upon how it is administered. Intravenous injection is the fastest route of administration, causing blood concentrations to rise the most quickly, followed by smoking, suppository insertion (anal or vaginal), snorting and ingestion.

Effects can last from five to eight hours, typically peaking at around two or three hours after administration. Heroin’s relatively low half-life means dependent users may need to take the drug two or more times per day.

As with most opioids, unadulterated heroin does not cause many long-term complications other than dependence and constipation. It can suppress the immune system, and this may lead to opportunistic infections, which carry their own lasting effects.

However, heroin is usually far from unadulterated by the time it reaches the end user. Figures from the UK, for example, indicate the average purity of street heroin varies between 30 and 50 percent. Heroin seized at the border has purity levels of between 40 and 60 percent.

This variation can increase the likelihood of overdoses. Each set of hands the drug passes through would normally add further adulterants, reducing the strength of the drug. If steps in the distribution process are missed, the purity of the drug reaching the end user may be higher than they are used to, and they may not be able to tolerate the increase.

Also, tolerance typically decreases after a period of abstinence. If this occurs and the user takes a dose comparable to their previous use, they may experience effects that are much greater than expected, resulting in an overdose. Death from overdose can take anywhere from several minutes to several hours. It usually happens because the breathing reflex becomes suppressed, resulting in depletion of blood-oxygen levels (anoxia). However, because heroin can cause severe nausea, a significant number of deaths attributed to heroin overdose are actually caused by the unconscious victim choking on their own vomit.

Intravenous use of heroin with non-sterile needles and syringes may lead to contracting blood-borne diseases (e.g. HIV and hepatitis) poisoning from contaminants used to ‘cut’ the heroin and decreased kidney function, though this may be caused by contaminants or infectious disease rather than by heroin itself.

A range of treatments including behavioural therapies and medications can help addicted people stop using heroin and return to stable lives.

Medications include buprenorphine and methadone, both of which work by binding to the same cell receptors as heroin but more weakly, helping a person wean off the drug by reducing cravings. Users can also be prescribed naltrexone, which blocks opioid receptors and prevents the drug from having an effect. A more recent, longer-lasting version of naltrexone, administered by injection in a doctor’s surgery, can be used with patients who have trouble complying with naltrexone treatment in tablet form.

Heroin overdose is usually treated with an opioid antagonist, such as naloxone, which acts on the brain’s opioid receptors to reverse the effects. However, it may also precipitate immediate withdrawal symptoms.

It is difficult to think about heroin use in New Zealand without associating it with the Mr Asia Syndicate, which began with Marty Johnstone (Mr Asia) importing 450,000 ‘Buddha sticks’ (cannabis) into New Zealand in 1975. The Buddha sticks had been purchased for 10 cents each in Thailand and made Johnstone (Mr Asia) and his associate Terry Clarke (Mr Big) around NZ$3 million. They used the money to expand into importing heroin into New Zealand and Australia via Singapore.

In 1978, the import bill for heroin into Auckland alone was around NZ$34 million, which the syndicate onsold at 400 percent profit. The syndicate fell apart in 1979, however, when Clarke was convicted for arranging Johnstone’s murder and sentenced to life in prison.

Since the 1970s, heroin use in New Zealand has declined steadily, and nowadays it is not commonplace. There are a number of reasons for this. The main one is that demand for heroin is low because New Zealand’s injecting drug community is well enough served by pharmaceutical diversion – prescription medications and methadone sold illegally on the black market.

Other reasons include effective border controls and the fact that New Zealand does not really have cities big enough to allow for the large but clandestine networks needed to make its distribution profitable.

Exact figures for how many New Zealanders use heroin are hard to come by, but according to the 2007/08 Alcohol and Drug Use Survey, around 3.6 percent of New Zealanders aged 16–64 years had used an opiate (including heroin) for recreational purposes at some point in their lifetime. This equates to about 94,000 people.

Recent news

Beyond the bottle: Paddy, Guyon, and Lotta on life after alcohol

Well-known NZers share what it's like to live without alcohol in a culture that celebrates it at every turn

Funding boost and significant shift needed for health-based approach to drugs

A new paper sets out the Drug Foundation's vision for a health-based approach to drug harm

Expert Pharmac committee recommends funding for overdose reversal nasal spray

The expert committee has said funding for naloxone in the community should be a high priority