Are you old enough?

If recreational cannabis becomes legal in New Zealand, one thorny problem we’ll need to deal with is the legal purchasing age. How do we settle on an age that will reduce harm for the most young people and what are other countries doing? Rob Zorn explores a few of the issues and makes a tentative case for 18.

At or by the time of the next election, New Zealanders will vote on whether to legalise cannabis for recreational use. If we do legalise (or if we start by decriminalising), we’ll be joining a good number of other developed countries. So far, at least 23 jurisdictions have adopted some form of legalisation or decriminalisation. The last was Vermont. The next will probably be Canada.

Legalisation or decriminalisation in a progressive country like New Zealand almost looks inevitable – if not as a result of this referendum then soon. Governments and Ministers appear to be catching on that prohibition and the War on Drugs have failed and that the sky hasn’t fallen where cannabis laws have been relaxed.

The fact is, most New Zealanders now seem to accept that prohibition has not only failed to stop cannabis use but has also fared poorly at protecting both individuals and communities from the harms cannabis can cause. An August 2017 Drug Foundation poll revealed 65 percent of us favour either legalisation or decriminalisation.

If we took the legalisation route, moving from a prohibitionist model to a regulated market would not be without its challenges, and one issue we would need to tackle is the legal purchase age. Just when is a person old enough to responsibly decide to buy and use a psychoactive substance?

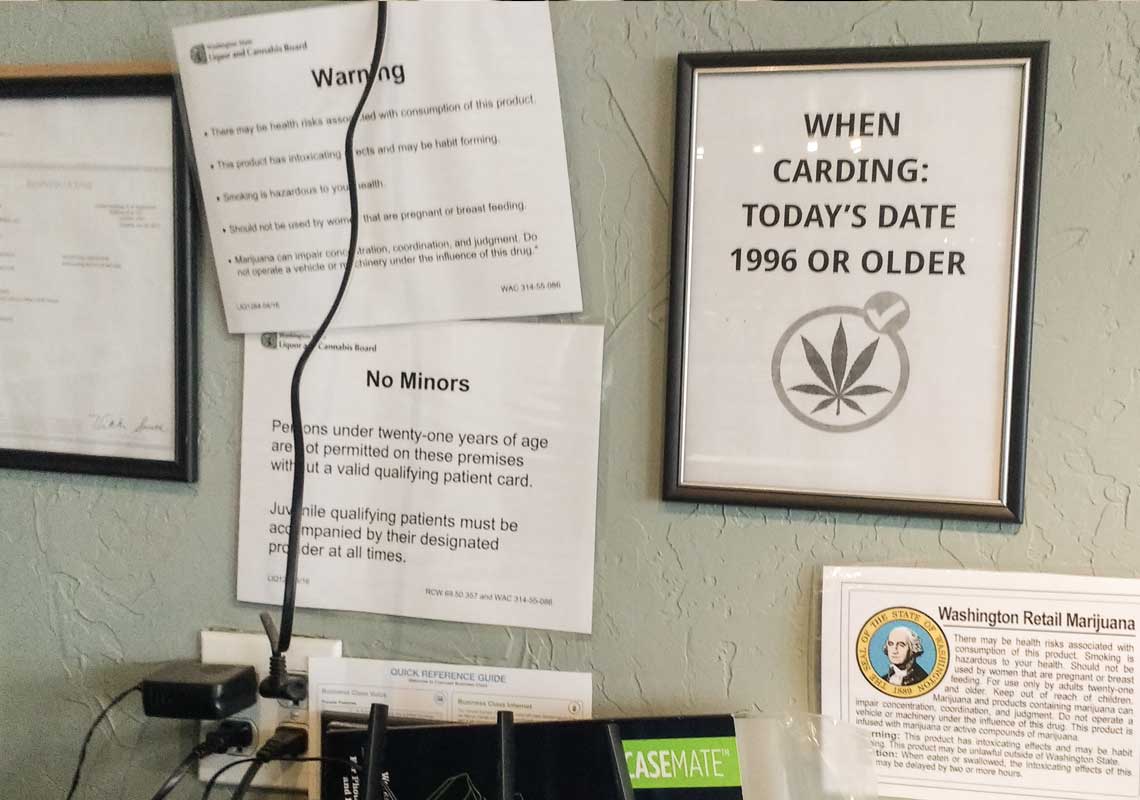

Cannabis legal age signage

What about 18?

In Whakawātea te Huarahi – A model drug law to 2020 and beyond, the Drug Foundation proposes a legal purchase age of 18. Its reasoning is that 18–25-year olds are already the largest cannabis-consuming group in New Zealand. According to the last New Zealand Health Survey (2012/13), 24 percent of young people aged 15–24 used cannabis in the last year, and 7 percent used it at least weekly. It would be far preferable that these young people use the drug in a legal, controlled and harm reductionist environment.

It’s a significant part of the Drug Foundation’s proposed model that all cannabis sales are accompanied by evidence-based harm reduction messages. For young people, this could include information about the damage cannabis does to developing adolescent brains, the potential for addiction and where to go for help when use becomes problematic. Controls on potency could also mean that young people who purchase cannabis legally would have reduced risk of harming their brains or mental health.

Another compelling argument for setting the legal purchase age as low as 18 is the impact it should have on the black market cannabis industry – often controlled by gangs. People who buy black market cannabis are participating in an illegal activity where there are no controls over potency and contaminants and, probably, little regard for customer health and wellbeing. A lot of harms can result from all these things, not least of which is the access that purchasers may gain to more dangerous drugs through contact with dealers.

We can be fairly certain that many young people, whatever age we set, will continue to use the black market if they can’t purchase cannabis legally. So, the argument goes, the higher we set the purchase age, the more potential customers we leave in the hands of gangs and outlaws. The lower we set it, the more ‘adults’ will turn to legitimate and legal sources. With a diminished market and reduced profitability, there is less incentive, and the hope is black marketeers will close their nefarious businesses and go out and get real jobs.

Lastly, there’s the human rights issue. At 18, you can go to war, vote in elections and, importantly, purchase alcohol. It doesn’t seem right then that cannabis – on the face of it a less-harmful drug than alcohol – remains off limits. And 18 does seem to be the default age of majority in New Zealand. Legally, it’s actually 20, but the only things a person under 20 can’t lawfully do are enter a casino or drive with any alcohol in their system.

But is 18 really a sensible choice from a health perspective given the emerging and burgeoning evidence about the effects of cannabis on the adolescent brain? Studies suggest regular cannabis use can disrupt the development of the brain’s neurochemistry and that this brain development doesn’t stop until a person is in their mid-20s. Resulting cognitive impairments can include diminished attention spans, memory and verbal learning skills. A 2008 New Zealand study published in Addiction has further linked higher cannabis use in people aged 14–25 with lower educational attainment, income and employment.

... the higher we set the purchase age, the more potential customers we leave in the hands of gangs and outlaws.

Research has also linked adolescent cannabis use with psychosis onset, where a pre-existing vulnerability exists, and a 2014 New Zealand and Australian longitudinal study published in The Lancet Psychology reported high rates of suicide attempts later in life for those who used cannabis daily before 17 years.

Concerns around these health effects on young people have led the Canadian Medical Association (CMA) to firmly oppose a legal age of 18. They advocate for 21 as a practical minimum, though ideally, they’d like the age set even higher.

“In a perfect world what we would recommend based solely on the scientific evidence is an age of legalisation of 25,” CMA Vice President of Medical Professionalism told the Canadian Medical Association Journal last year.

It’s not hard to find similar concerns closer to home, even amongst those supporting legalisation as a public health good. In the Summer 2017 edition of Addiction Standard, National Addiction Sector Director Doug Sellman called nonsense on the argument that if you’re old enough to vote and fight for your country, you’re old enough to buy a beer “and a bong”.

“[Our 18-year-old soldiers and voters] don’t fight or vote independently, but rather are exposed to a considerable amount of adult influence and guidance in their killing and voting,” he wrote.

He argues that lowering the drinking age has encouraged a youth drinking culture to thrive and that this would also be the case with cannabis under a legal, regulated market. He points out there is “substantial literature” showing the damage to young people from reducing the drinking age from 20 to 18 years.

And there is. For example, in its 2010 report Alcohol in Our Lives: Curbing the harm, the Law Commission cited a number of studies to back its recommendation to return the legal age for purchasing alcohol to 20. It said lowering the purchase age to 18 saw an increase in drink driving, car crashes, injuries and deaths and other health and social harms among young people.

But I am not so sure we can extrapolate so neatly and assume that what happened with the alcohol purchase age is exactly what will happen with cannabis. Alcohol is used at a vastly higher rate and is much more widely available than any other drug. It’s also already part of mainstream culture, has always been legal to purchase and is heavily advertised. Cannabis use is much less widespread, and cannabis would be moving from an illegal to legal status. The cultures and behaviours around the use of these two substances are also significantly different, and all this could lead to quite different and perhaps unexpected outcomes.

It could also be pointed out that, since legalisation, according to studies and news reports, cannabis use by adolescents in Colorado, including high school students, has declined by at least four percentage points to its lowest level in more than a decade.

Cannabis use by high school students in Washington has remained stable or declined slightly since legalisation depending on the county, according to a recent report by the Washington State Institute for Public Policy. However, the report also concedes that there is no evidence that legalisation has directly caused any decline. It’s just too early to tell.

“Without more data we don’t know if the decline would be greater if marijuana remained illegal,” said report author Adam Darnell.

And it’s hard to tell whether the same declines occurring in Washington and Colorado would occur in New Zealand. Our situations are quite different in that the cannabis markets in these states are a little less regulated than we would probably like to see, and the legal purchase age in both states is 21 not 18.

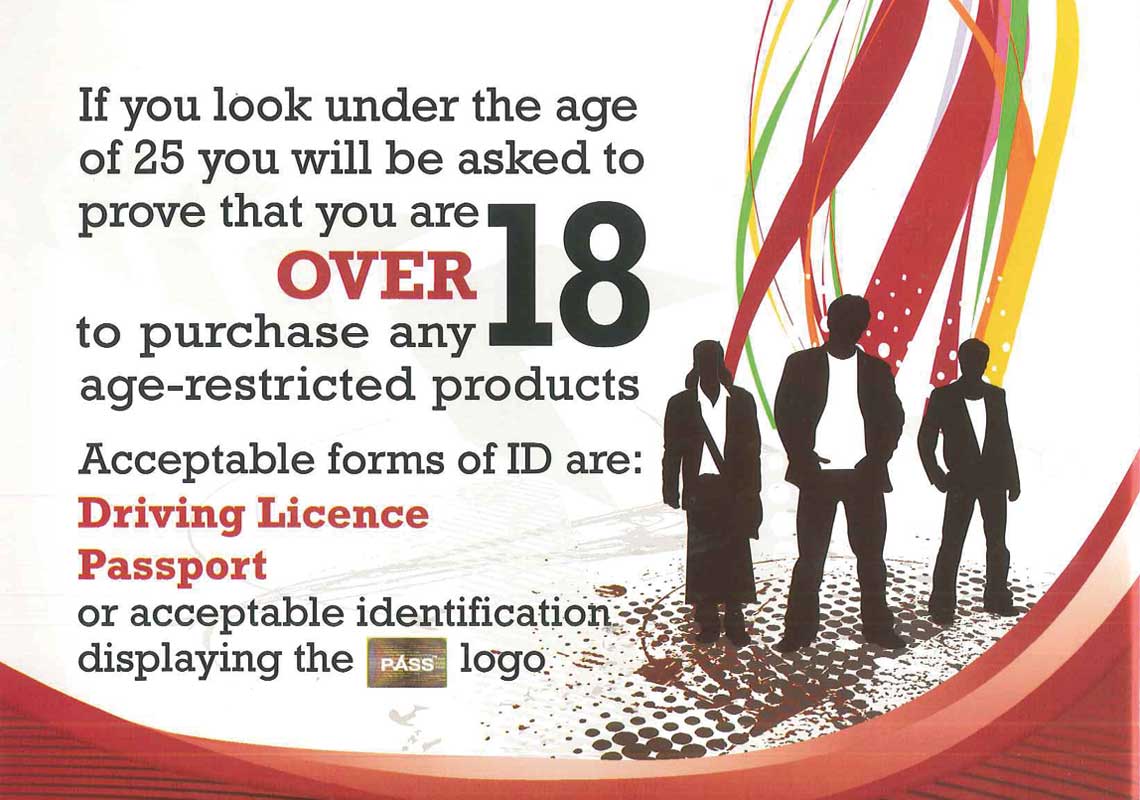

cannabis legal age signage: if you look under 25, you will be asked to prove you are over 18

Canada and other jurisdictions

What is noticeable is that just about every jurisdiction that has legalised recreational cannabis use has tied the legal age of purchase to the age for purchasing alcohol and tobacco – no doubt for the same human rights and consistency reasons we touched on earlier.

The next country to tie the two will be Canada, which is on track to fully legalise recreational cannabis by July this year. This will make it just the second country to allow the drug nationwide after Uruguay.

Canada’s cannabis usage is similar to New Zealand’s. There, 8 percent of adults over the age of 25 reported past-year use in 2013, whereas 25 percent of youth aged 15–24 reported past-year use.

Canada will be a country to watch as it seeks to set up a regulated cannabis supply system that will be similar in many ways to the model proposed for New Zealand by the Drug Foundation. In November 2016, Canada’s Task Force on Cannabis Legalization and Regulation published its report, A framework for the legalization and regulation of cannabis in Canada, which the Canadian Federal Government considered while developing its legalisation legislation.

The Task Force recommended the Federal Government set a national minimum purchase age at 18 and suggested provinces and territories should be free to raise (but not lower) it to harmonise it with their minimum age for alcohol purchase. This was despite advice from some public health sources that this could lead to “border shopping” by young people seeking to purchase cannabis in a neighbouring province or territory where the age is lower – which currently happens with alcohol.

It should be noted, however, that a primary reason for the suggested age of 18 was that “setting the bar for legal access too high could result in a range of unintended consequences, such as leading those consumers to continue to purchase cannabis on the illicit market”.

Other details such as who can sell cannabis will also be largely left up to the country’s provinces. So far, five of Canada’s 10 provinces have come forward with frameworks for retail sale. In Ontario, Quebec and New Brunswick, sales will be run by provincial government-owned entities. The western provinces of Manitoba and Alberta have said they will license private retailers. In most provinces, the legal purchase age will be set at 18. In Ontario, Canada’s most populous province, it will be 19. The Federal Government’s proposed legislation will also permit adults to grow up to four cannabis plants at home, although Quebec has announced it will allow no such thing.

A number of things in the Task Force’s report will ring some bells for those who have read Whakawātea te Huarahi.

The Task Force acknowledged that age restrictions on their own would not dissuade use by young people. Other actions including prevention, education, treatment and advertising restrictions will be required to achieve this objective.

It also said the young people it consulted did not believe setting a minimum age alone would prevent their peers from using cannabis. However, the report said there was a general recognition that a minimum age would have value as a “societal marker”, establishing cannabis use as an activity for adults only – at an age at which responsible and individual decision making is expected and respected. It also suggested 18 was a well-established milestone in Canadian society marking adulthood.

The same could be said for New Zealand, and we should be doing what we can to empower our young people to make decisions about and for themselves. They are generally competent enough, and reported worldwide declines in risky behaviours by youth suggest they are listening to health and harm reduction messages.

Bringing it all back home

Whether we like it or not, it seems we are stuck with 18 as the legal purchase age for alcohol into the foreseeable future. In the past, the Drug Foundation has backed the Law Commission’s call for this age to be returned to 20, but that ship has well and truly sailed for now.

Given this, it just doesn’t seem sensible to tell our young people it’s fine for them to purchase and drink alcohol at 18 but that buying cannabis is illegal for them until they’re 20. That would inherently suggest alcohol is safer than cannabis, and do we really want to be saying that at a time when honesty and credibility from those leading the legalisation debate will be needed more than ever?

In How to regulate cannabis: a practical guide, the Transform Drug Policy Foundation says, “Where [the age] threshold should lie for a given drug product will depend on a range of pragmatic choices … informed by objective risk assessments … balanced in accordance with priorities …”.

Pragmatically, 18 seems the most sensible choice as we balance the risk of under-the-radar black market use against the priorities of consistency, safer use and harm reduction opportunities. It’s not a perfect solution because there isn’t one. It’s not about encouraging young people to use cannabis. It’s about finding a balance that will result in the least harm to the greatest number.

Granted, our young people are not a homogeneous group, and if we don’t get the regulatory framework right, there are some who will more likely bear the brunt of that failure, such as Māori who are disproportionately targeted under current law. But bringing young people’s use out into the open where we can monitor it and provide help where needed will reduce harm generally and be a great leap forward. We may not know exactly what will happen, but anything would be better than the prohibitionist approach we’re taking now.

Recent news

Beyond the bottle: Paddy, Guyon, and Lotta on life after alcohol

Well-known NZers share what it's like to live without alcohol in a culture that celebrates it at every turn

Funding boost and significant shift needed for health-based approach to drugs

A new paper sets out the Drug Foundation's vision for a health-based approach to drug harm

Expert Pharmac committee recommends funding for overdose reversal nasal spray

The expert committee has said funding for naloxone in the community should be a high priority