Q&A: Costing drug policy options

Economist Shamubeel Eaqub of Sense Partners spoke to Emma Espiner about a new report that makes the case for a health-based approach to drug policy as not only the most compassionate but the best economic choice for Aotearoa.

Q What did you set out to achieve with this report?

A The War on Drugs hasn’t worked. We can see the cost of getting it wrong everywhere in our society. We wanted to know what is the alternative? Is there a different way of doing it, and would we be better off? We wanted to know the impact on governments who foot the bill and the impact on society because, ultimately, the cost is borne by all of us.

We have been waging this war for decades. We’re sending people to prison, shutting people out of labour markets, limiting the future potential of our young people. These are things we know – the cumulative effects of this futile war. Yet when a new problem arises, like what we’re seeing with synthetic cannabis right now, the first response is criminalise it and punish people even harder.

In this report, we lay out what we’re spending on policing, enforcement and punishing people and we ask what if we did it differently? What if we imagined a different future where things could be better?

Q You looked at both the decriminalisation of all drugs and the legalisation of cannabis in this report. Why did you separate the two?

A We based our report on Whakawātea te Huarahi, the New Zealand Drug Foundation’s model drug policy. This model proposes that the use and possession of all illicit drugs is decriminalised but that supply will remain illegal. It also proposes the legalisation of the use and supply of cannabis and a significant investment in harm reduction, treatment services and drug education. You will see from the report that our final recommendation is a combination of all three elements.

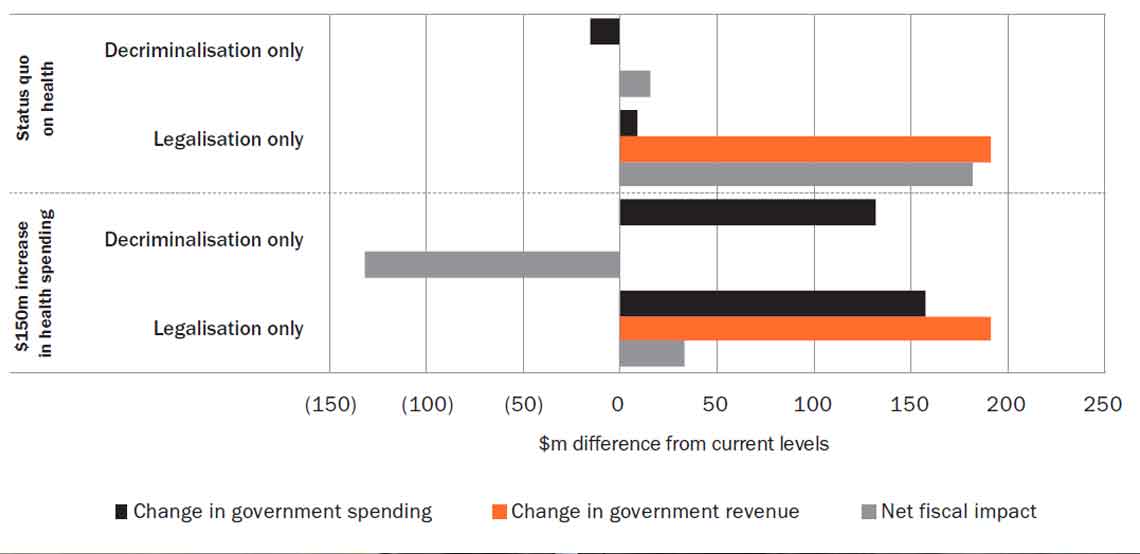

We found that both approaches would be beneficial from both a fiscal and a social perspective. Decriminalisation alone would make society better off by around $34–83 million a year, primarily through reduced criminal justice costs ($27–46 million a year).

Unfortunately, decriminalisation alone won’t pay for the increased costs associated with the boost to drug and alcohol harm-reduction services and drug education, which we have estimated at $150 million and $9 million respectively. We know that at least 50,000 additional people would access health services for drug use if they were available right now. That’s going to cost a lot.

This is where the legalisation of cannabis comes in. Our report suggests that approximately $190–250 million a year would be delivered to the government through the legalisation of cannabis and the establishment of a regulated market. It’s worth noting that our findings align with those of Treasury in 2016, and in fact, we’ve been slightly more conservative than that in our estimates. Not only that, but the investment in health services we’ve proposed is needed to keep up with current demand – regardless of what we do with drug law reform.

Q Did you experience any challenges in collecting data on the impacts you consider under social costs?

A It is difficult. We’re trying to quantify the benefit of reduced harm to people who, through this pointless criminal justice approach to drug policy, have seen their opportunities to thrive reduced. There are existing estimates of the social costs. For instance, the Ministry of Health puts the cost of drug harm and interventions at $1.8 billion, $890 million of which was community harm – estimated from indicators such as people’s willingness to pay for harm-reduction services, acquisitive crimes and estimates of investments in organised crime. But it doesn’t adequately capture the loss of opportunities over the life course for those penalised for drug use. This is a notoriously difficult area, and I think you’ll find that the social impact costs we’ve estimated would be very conservative.

Q Were you personally convinced by this argument for reform?

A Yes. Decriminalisation with legalisation of cannabis must be the way we do it. There are two reasons. The compelling evidence from Portugal is that decriminalisation works – but only if you put comprehensive supports around it. This isn’t confined to drug and alcohol harm-reduction services, it’s everything – supporting people into housing, job-seeker support, educational opportunities. But I’m a pragmatist and I appreciate that there’s no way we’re going to get funding for the support services we need unless we present our government with a way to pay for it.

You mention evidence, and unfortunately, drug policy has been an evidence-free space. It’s much easier politically to be seen to be ‘tough on crime’ than to do the evidence-based thing. It’s not like we don’t know the science or the history. If you’re so unconvinced, just get on a plane and go to Portugal. Just go and have a look!

Q So you don’t have any sympathy for the Minister of Health signalling that he wants to put synthetics into the drug schedule as a Class A?

A No. It’s inconsistent with the supposed health-based philosophy around these issues. The schedule is not linked to harm in any way. This is the whole ad hoc approach that’s gotten us to where we are now. If you’re going to put synthetics into the schedule and expect it to somehow reduce harm, why not chuck alcohol in there as well? Alcohol causes immense health and social harm.

When I think about synthetics, I think it’s a lesson to us in how we manage any new drug policy. The synthetics problem has come out of bad legislation and a regime that became so difficult that we drove everything underground. It’s a good warning about why it’s so important that we get this right.

Q Establishing a market for cannabis makes sense from a cost perspective, but what about the argument that this would be a new and tacit endorsement of a drug? Not only that, but it could become subject to the same sorts of marketing and inducements for use that we’ve seen in tobacco and alcohol.

A You’re not wrong, but I suggest you think about relative harms. We shouldn’t pretend that any drug does not have the potential to cause harm, but we should think about the scale of the harm and whether the alternative – what we have right now – is any better. What we’ve got right now is an unregulated market worth more than $500 million a year, entirely oriented around the criminal underground. And despite this, most New Zealanders have tried cannabis, so it’s not even as if the criminal association makes it difficult for people to access cannabis. It just makes it more dangerous for people to get it.

If we bring cannabis into a regulated marketplace, we can control price, quality and potency and we can tax the activity, returning approximately $190–250 million to the government every year.

Q How much do we move the dial with this activity for those most hurt by our current policy settings? I can see that a regulated cannabis market might improve the lifestyle of someone sitting in Grey Lynn who can go out for a coffee and a joint and have a nice time, but what does this do for whānau in areas where the harms are a lot more significant? How do you put equity into the equation?

A The big part of removing the harm from those communities is by taking the criminal element away. I agree – having access to a regulated, legal cannabis market probably isn’t going to make much of a difference to those families. But they will notice a difference when the criminal elements are taken away.

Q In your report, you’ve noted the steady decline in convictions for drug use over time. This is consistent with a recent analysis that suggests Police have been quietly liberalising their approach to drug use and possession. Some might say this is enough of a change, but I look at that approach and the evidence of racism in the criminal justice system and I’m less confident that asking the Police to exercise their discretion in an equitable manner for all people who use drugs irrespective of their skin colour is going to be enough.

A Absolutely. This is why we need to legislate. There needs to be clarity about this sort of thing or else unconscious bias or whatever you want to call it will persist.

There also still needs to be a strong social safety net for everyone. This policy isn’t going to fix entrenched intergenerational poverty, a lack of secure employment options or educational pathways. But we do know that the existing approach is making things worse, and we can’t in good conscience allow that to continue.

Note: Sense Partners’ report Estimating the impact of drug policy options was commissioned by the New Zealand Drug Foundation , the NZ Needle Exchange Programme and Matua Raki.

Conservative estimates of the impact of drug policies on government finances

Bar graph showing the impact on govt finances, comparing the status quo with a proposed $150m increase in health spending - Notes: Decriminalisation and legalisation both improve the government fiscal position, because the criminal-justice-based system is more expensive than a health-based approach. The savings would not be enough to fund a necessary increase in prevention, education and addiction treatment services. Legalisation of cannabis would provide the necessary increase in revenue.

Recent news

Beyond the bottle: Paddy, Guyon, and Lotta on life after alcohol

Well-known NZers share what it's like to live without alcohol in a culture that celebrates it at every turn

Funding boost and significant shift needed for health-based approach to drugs

A new paper sets out the Drug Foundation's vision for a health-based approach to drug harm

Expert Pharmac committee recommends funding for overdose reversal nasal spray

The expert committee has said funding for naloxone in the community should be a high priority