Getting the measure of meth

With a host of agencies diligently working together to tackle New Zealand’s meth problem over the last six years, it’s timely to ask how things are going. Matt Black looks beyond the official statistics, to provide this up-to-the minute report.

In 2009, the New Zealand Government launched the Methamphetamine Action Plan – a response to the reportedly large numbers of people using meth at that time. The Ministry of Health Household Survey had put the numbers at around 2.2 percent of the general population, or approximately 80,000 people – disproportionately high compared to comparable western societies. The plan would be run out of the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (so seriously did the National Government of 2008 take the issue) rather than domiciled in the more normal home of the Police or Ministry of Health.

The principal rationale for making the policy resident at the ninth floor of the Beehive was that it would encourage a cross-agency approach, with co-operative success – or failure – being reported directly to a very determined and incredibly popular Prime Minister John Key. Four years later, in 2013, the same survey put the number of meth users at around 1 percent, or 40,000 people in the general population – on the face of it, quite a remarkable achievement.

But has meth use in New Zealand really halved? Not everyone close to the issue is convinced about the numbers, or even the survey itself. Given the propensity of governments everywhere to spin the positive findings of reports and minimise the negative ones, the question is worth asking.

The numbers are right, Key reassures me down the phone. One of his senior press secretaries has very kindly set up the interview in a spare 10 minutes from the back seat of his Crown limousine. I mention how ironic it is that the subject of meth might be welcome, given the dominant media discourse on Auckland’s property prices. From his presumably rarefied environment of leather and walnut, he laughs affably and tells me he has to be ready to discuss any topic, including the presently running series of The Bachelor, and that he’s convinced that meth use in New Zealand really is down.

“When I first became Prime Minister, we went away and set about doing a whole-of-government response. We thought, while it’s easy for politicians to get up and make claims about drugs, everybody knows how challenging this whole environment is, how difficult it is for people who are addicted to some form of substance abuse. One of the conclusions we came to was that we didn’t want something that met the 6 o’clock news test but then didn’t solve the problem. So we went across a variety of agencies from Customs to Health to the Police,” Key explained.

“One of the reasons I’m convinced the numbers are right, that’s there’s been a reduction from 2.2 to 1 percent, is that there’s been such a comprehensive response. The second thing is that the samples we use are very large, and it’s working through the Health Survey, which we generally think is robust. And given the anecdotal evidence we get from Police and others, we think that’s about right.”

Later that afternoon, the Police announce that, in two seizures run closely together, Operation Wand and Operation Sorrento, they have seized 123kg of meth with a street value they place at $123 million. Even given the authorities’ creative accounting around the nature of wholesale economics, it’s a simply enormous amount of meth to seize – 18kg more than all the meth seized in 2014. Laid out on tables for the press to photograph, it looks like a giant collection of crystallised rain that might have fallen on the Prime Minister’s good news parade – only five hours after we talked.

I think ultimately our success is measured in the crime we prevent, and if we can adopt a different resolution that leads to prevention of future offending, then we’ve got a better outcome.

Detective inspector Bruce Good

One of the Prime Minister’s major allies (and instruments) in the war on meth is Assistant Commissioner Malcolm Burgess. He was skeptical of the downward trend in the statistics the last time I interviewed him in 2014, and eight months on, in light of these two enormous busts, he shows no sign of changing his mind.

“I think we’re probably getting mixed messages around that,” he says into the phone, the wryness in his delivery as reliable as ever.

“Some of the survey data, and Chris Wilkins’ data out of Massey, suggests that the numbers are stable or potentially diminishing. But balanced against that, we’re seeing pretty significant amounts of drugs either being manufactured or imported.”

He doesn’t distinguish between homemade or imported product.

“We’ve still got both. We’re dealing with people who are in this for business. They’re buying cheap and selling high, and that’s the case whether it’s precursor or the finished product. The very large amounts that came into New Zealand, had they not been apprehended, I suspect probably would have flooded the market. We don’t generally see seizures of that size.” His colleague Detective Inspector Bruce Good was straightforward in the press release.

“To find 20 kilograms ready or being prepared for market at one clandestine (clan) lab shows the scale of organised criminal operation we have infiltrated during Operation Wand. Unfortunately, it also suggests that the market for meth remains strong in New Zealand.”

Good also said Police were not aware of any links between the organised criminal groups involved in each operation, meaning the protagonists were operating independently of each other.

Denis O'Reilly - Denis O'Reilly

If a country as small as New Zealand has the criminal distribution network to move 123kg of meth, this might suggest the problem is alive and well. Has there been an undercounting of some kind, some anomaly in the statistics? One suggested possibility is the way users are processed under the new policy of Policing Excellence in Future, which is about “alternative resolutions”, according to Burgess. But he is dismissive of the suggestion that the policy is affecting the statistics.

“Regardless of the crime type, at a lower level – and drug use might be one of those – there is the potential for a pre-charge warning to be issued. There are quite a few guidelines around it, and for more serious offending, it doesn’t apply. I wouldn’t be surprised if people who are picked up for using are going to be offered alternative resolution in some cases. But it doesn’t affect the numbers at all. We still record the fact that we’ve apprehended someone for the offence, and the offence data for meth use and supply for the last year is actually higher. So that shouldn’t have any effect at all on the data. I think ultimately our success is measured in the crime we prevent, and if we can adopt a different resolution that leads to prevention of future offending, then we’ve got a better outcome.”

Key is equally adamant that the policy is about good policing and is having no effect on the numbers.

“One thing we know is that about 30 percent of clan labs were using domestically sourced pseudoephedrine, and we know that number has significantly dropped. We can actually measure that when they go and bust those clan labs. The second things is that, while there are some very, very high-profile seizures, our tools have got a lot better. I think what we have to accept is that it’s a very lucrative business for people, so there are always people who will try. But I actually do think that, for the most part, our numbers are right.”

But what about the survey methodology itself? Is it robust? One person critical of the Household Survey is Dr Chris Wilkins, one author of Massey University’s report on recent trends in illegal drug use in New Zealand. The latest report was published in October 2014, well after the survey was released. Sitting in someone else’s small and sterile office in the SHORE and Whäriki Research Centre on Symonds Street, surrounded by folders of their accounts, he concedes that the survey results are “probably about right”, but has doubts over the survey's methodology.

“The problem with their surveying has been that they’ve changed the methodology pretty much every time they’ve done that survey. They talk about how they’re identifying trends, but those little changes in the methodology mean you have to be a little bit cautious. I don’t know why they continue to tinker with it, because basically the bedrock of trend analysis [is] you have to be quite disciplined about the methodology.”

Wilkins also worries that, while meth use may be down in the general population, it remains entrenched among other, vulnerable sections of society.

“We’re doing an arrestee survey, and something like 30 percent of them have used meth in the last 12 months. That’s pretty high. The general trend is that the new trend of a drug has burnt itself out, [but] often it ends up in particularly vulnerable populations like arrestees, frequent drug users, lower socio-economic areas, and it just stays there at quite a high level for those groups.”

Wilkins says that, if there is a changing demographic of meth use in New Zealand, the way it comes to market is changing as well

“From the manufacturers’ point of view, they will respond to different risks in different parts of the supply chain and what’s available to them. For local production, over time, there’s been much greater controls over precursors. We picked up about one or two years ago that the result of that seemed to be people suddenly got interested in crystal methamphetamine, which is usually the imported, manufactured [product], rather than importing pseudoephedrine.

I don’t know what’s going on at a macro level. But I do know that supply has stayed constant, if not increased in its ease of availability and quality, and that price has remained constant.

Denis O'Reilly

Those kind of production things can change relatively quickly, depending on how the players see the risks changing. Combined with that, there has been a decline in the number of meth labs detected. But that change has been going on for a long time. It used to be somewhere over 200, but now it’s 100 or so, and it’s been declining pretty steadily. That’s just the number of labs. There are alternative explanations that perhaps the labs are more professional or they’re hidden more or they’re higher production, and that’s plausible. They were seizing incredible amounts of pseudoephedrine year after year. If you converted that into meth, you could produce enough for the entire market. I think that, over time, that’s slowly going to make an impact. Over time, people might be thinking, well, they’ve got a good handle on seizing pseudoephedrine, so why don’t I just try importing the finished product?”

Denis O’Reilly manages a national programme called Mokai Whänau Ora. Its aim is to reduce the manufacture, distribution and use of meth and is part of the Ministry of Health’s Community Action Youth and Drugs service. He is highly qualified academically and is also well known for his relationships with some of New Zealand’s gangs, particularly the Black Power and Mongrel Mob, considered by the Police to be instrumental in the meth trade. Uniquely placed to comment on the issue, he sees the same entrenchment of meth use among lower socio-economic groups and also wonders if there’s a new focus on importing ready-made product.

“I think we’ve weathered the big storm,” he says, looking reflectively out over his balcony towards Ocean Beach, roaring loudly only 50 metres away. The week before, Cyclone Pam had brought the sea almost to the doorstep.

“The epidemic, if you like. I do think it’s got a bit sounder and saner since then. It’s more endemic now. And the questions are, is there deep usage amongst much smaller groups, has it siloed or is just lurking beneath the surface in a much larger way? I had [a visitor] here yesterday.

He works for one of the horizontal drilling companies putting in all the fibre optics, some sort of trust structure with a Christian ethos, and they’ve recruited these young Mäori. Suddenly, these kids, for the first time in their lives, are actually getting a reasonably good pay. And he was saying [meth] is something they’re really confronting at the moment. Now that would be the first indicator of something fresh going on, a market relaunch. But I’ve noticed that there’s no diminution in supply in any practical terms, and it’s probably easier to get than cannabis in a lot of places – Auckland, for example.

“Do we see supply-driven spikes? We used to see all the drama, but have people learned to manage their usage better? Are they more aware of what binge amounts do? The story I get continually is that the big Asian crews are bringing it in, possibly ready-made. It’s liquid soluble and can come in any substance. Has someone cracked the code? And that seems to be the common thing in the distribution market – crews bringing in pretty significant amounts, and the crews get rid of it pretty smartly.”

Many of the sources spoken to for this story felt the idea that meth was in retreat was risible. One working girl wanted to know, “If they’re so on top of it, how come it’s easier to get than weed?” This was a fairly widespread sentiment. One brothel manager estimated that around 20 percent of her staff were using. That figure was put as high as 90 percent at an establishment she’d previously worked at, and she claimed the problem was endemic to clients, too.

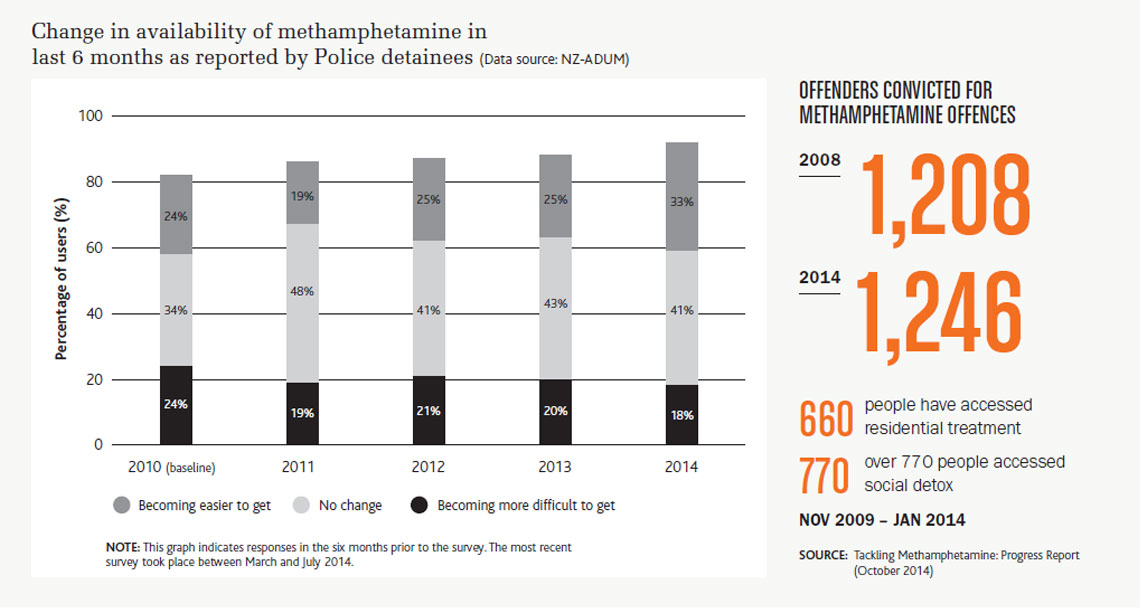

Change in availability of methamphetamine in last 6 months as reported by Police detainees (Data source: NZ-ADUM) - Methamphetamine action plan: key statistics

One former cook felt the problem was as bad as it had ever been, only much better hidden, with larger-scale, more commercial and more remote clan labs now the norm. The obvious problem with the testimony of these sources is that it’s unscientific. Being inside a highly entrenched subgroup, as Wilkins would so identify them, doesn’t allow for an accurate perspective of the national picture. What is true is that they were uniformly consistent in their views. The report produced by Massey says, “The frequent drug users reported the current availability of meth was easy/very easy.”

O’Reilly: “I don’t know what’s going on at a macro level. But I do know that supply has stayed constant, if not increased in its ease of availability and quality, and that price has remained constant. The way Chris Wilkins’ model works, you should see these fluctuations in price.” He laughs. “But after all, it’s a drug! And people don’t make rational decisions. A tinny is a tinny is a tinny, and it’s $20. A point is a point is a point, and [it’s $100]. Why would you sell it for anything less? What the market expects, the market gets. Price discrepancy is a misnomer.”

Wilkins: “You can say that, overall in the New Zealand population, meth use is pretty low, it’s 1 percent or something, but if the problem is that, in some neighbourhoods, 30–40 percent of people are using meth, then that’s still a big problem for them. And that’s still an issue for everyone else.”

One place where there may well be a resurgence above the national average, as suggested by the statistics, is Christchurch. Paul Rout, the CEO of the Alcohol and Drug Association of New Zealand (ADANZ), which operates and manages the Alcohol Drug helpline, says peak callers from there are reporting higher availability. Joining me by phone from the Garden City, he sounds weary of dealing with the issue.

“I think the best data we can supply is the number of people calling the Alcohol Drug Helpline regarding meth. Over the last two years, we’ve had a 36 percent increase in the number of people calling. Currently, meth is our number two drug behind alcohol. It’s taken over from cannabis – 14 percent of our calls are meth related.”

He pauses. “Calls to the helpline don’t necessarily indicate there’s a massive use increase in the community. It might be that some of that is related to more people seeking help. But we generally find as we did with synthetic cannabinoids that, when there’s a big increase in the community, [that] generates into calls to us.”

O’Reilly is more excitable. “Christchurch is going to be the gang capital. It’s going to be Wellington in the 1970s. You’ve got all these young men down there rebuilding. There’s going to be such gang complexities that people will say, where did this come from? But it’s a function of who’s out there. The money’s out there, you’ve got all these young Mäori fellas using meth. It’s attractive. Party like an animal, drink like a fish, fuck like a horse. Until it bites.”

Burgess isn’t buying it.

“Look, I think we’re probably seeing a slight increase in Christchurch, but I’m not sure I’d buy in to the argument that it’s going to become the gang capital of New Zealand. We’ve got a lot people that have gone there because there’s a lot of employment opportunities, and people are working hard and making good money. I guess if you’re going to increase the population, and it’s a population that’s reasonably well funded and has a bit of time on its hands, then there’s a chance you’re going to increase the attendance at the local pubs or clubs, or they might potentially get involved in other pastimes.

Rout says Christchurch may be an anomaly in the sense that people who manufacture and distribute methamphetamine are pretty sharp business people. They’ve identified an area such as Canterbury, which historically has had lower meth use compared to some of the North Island cities.

“There’s certainly a lot of reports from Police around significantly increased levels of gang recruitment across the board, and a lot of these gangs are involved in meth distribution. That all paints a picture of an increase.”

The Methamphetamine Action Plan report of October 2014 is a highly sanguine document. It ticks the right boxes – what Key calls the “6 o’clock news test” – but it’s doubtful it’s reflective of reality in New Zealand, as expressed by either the scientific or anecdotal research. Every status in ‘Part 1: Progress on cross – agency actions since 2009’ is listed as “complete”, with the only exceptions being the government’s legislative agenda. Perhaps a better term to use would be “progress”.

Certainly one action some feel is far from complete is to ‘Provide better routes into treatment’.

Rout becomes passionate when outlining that more people would come forward for treatment if they knew what was available.

“What I would really like to see is active promotion of services for meth users. We’re convinced that, if we could actively promote our meth help team, we could generate enough work for a significant increase in resource. As with most things, we often assume that people know where they can get help, but that’s a big assumption. If we’re really to promote help-seeking behaviour for meth problems, then we could generate a significant increase in the number of people getting help.”

Robert Steenhuisen is the Regional Manager of Community Alcohol and Drug Services (CADS) for Auckland. He meets me in his office at Pitman House, a residential treatment centre. A small bookshelf is filled with expert literature on the subject of drugs and recovery. He tells me with a soft Teutonic accent that, over the last 12 months, CADS saw 14,858 people, and that if meth abuse and dependence are taken together – “an artificial distinction” – then it’s 6.8 percent of people. He says CADS also keeps a Deprivation Index for its clients and points at the printout he’s just handed me.

“If you look at the bottom [line], that’s where the majority of people are. When you look at those numbers, what you see is a whole lot of converging trends. Poor people have less resources to cope with their problems. Poor people are more likely to come to the attention of Police. They might have fewer social skills, but then again, severe alcohol and drug use contributes to you descending into the social deprivation class. You have no money, so you end up renting in a crap neighbourhood. Things fall apart, so you drink more or use more meth.”

At the coalface of the problem, he’s ambivalent about whether the numbers are up or down.

“I think, in the end, the number of people is irrelevant. The people who present to us present in a real state. Obviously, their meth use drives every other aspect of their lives, so that’s psychological, social, general wellbeing and so on, and they have a big problem stopping it. When you look at the users, it’s predominantly a health issue. You have to assist people in making lifestyle changes. You cannot punish a person out of meth dependence.”

So has New Zealand found the right policy balance between enforcement and health measures?

Key believes it’s being redressed.

“We’ve certainly significantly improved that balance. One area of real concern has been the number of prisoners who are drug dependent, who weren’t getting treatment when they went to prison. Even though some of us might think intuitively that, if you have a custodial sentence, that will clean you up and dry you out, realistically, that actually isn’t the case. So now we have a programme of running everyone through a drug and alcohol programme that would need one or want one. We have increased the number of beds and support available. I think the agencies would argue that we need to spend more money in that area.

“If you think about it in a classic sort of market sense, there’s supply and demand, and if we can control the supply through better controls at the border and through banning local sales and all of these things, then the next bit is, if we can cut the demand, we can make it less attractive to those who want to set up a P business. So I think you’ve got to do both, it’s not enough just to go hard on the law enforcement. You’ve actually got to give help to the people who are using these drugs.”

O’Reilly laughs. “And that’s the thing you come to. If [treatment] is the only thing that works, then what are we doing all this other stuff for?”

Key believes the Methamphetamine Action Plan has been a success.

“Since 2009, the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet has run a six-monthly report for me. They put in data from all the relevant agencies. They look at how much P or pseudoephedrine has been detected, how many clan labs have been busted, the number of people admitting themselves and, through the Health Survey, the amount of reported usage. They also report to me on the proceeds of crime, which is around $11 million. We pour at least some of that money into better [enforcement] capacity or treatment.”

It has, he declares, “Unquestionably been worth it. Not just as a politician, but also as a parent. If you think about the pressure that a young person puts on a family if they’ve got a drug problem, it’s huge isn’t it? And we know from P that it leads to such mind-altering behaviour that you see some of the worst and most violent. So in my view it was a really good initial project for me. All of this happened during the 2008 to 2011 period, and we’re obviously still doing lots of work on it. So to my mind, it’s probably one of those ones where, without being silly about it, we probably don’t get a lot of credit, and maybe people don’t actually know about what we’ve done in this area. But at a personal level, I feel pleased we’ve allocated time and resources and tried to do something about tackling the issue.”

Photo credit: flickr.com/photos/eastbeach

Recent news

Beyond the bottle: Paddy, Guyon, and Lotta on life after alcohol

Well-known NZers share what it's like to live without alcohol in a culture that celebrates it at every turn

Funding boost and significant shift needed for health-based approach to drugs

A new paper sets out the Drug Foundation's vision for a health-based approach to drug harm

Expert Pharmac committee recommends funding for overdose reversal nasal spray

The expert committee has said funding for naloxone in the community should be a high priority