Hopes dashed and raised in NYC

The biggest global conversation on drug policy in the last 18 years took place in New York City 19-20 April 2016. A delegation of New Zealand NGOs joined diplomats, politicians, UN agencies and civil society representatives at the UN General Assembly Special Session (UNGASS). Russell Brown filed this report from the Big Apple.

UNGASS 2016 was supposed to embody hope for change. But here, in a crowded United Nations meeting room the morning before the General Assembly convenes, there seems little of that.

Getting Better Results: Aligning Drug Policy Objectives Within the Wider UN System is a side event organised by the permanent missions of New Zealand, Switzerland and Brazil along with several NGO groups and chaired by New Zealand’s Associate Health Minister Peter Dunne.

On the face of it, it’s a narrowly technical discussion about developing better metrics to assess the outcomes of drug control policy – and in particular, whether such policy serves the declared objectives of the UN family, the Sustainable Development Goals or SDGs. But almost every speaker writes off the chance of meaningful change at UNGASS. The tone of it all is strikingly bleak.

Nazlee Maghsoudi, Knowledge Translation Manager at the International Centre for Science in Drug Policy (ICSDP), laments a “critical missed opportunity” and declares that “the drug policy status quo will act as a barrier to attainment of the SDGs”.

Mike Trace, Chair of the International Drug Policy Consortium, recalls being at UNGASS 1998 and signing off the fateful slogan (“and it was a slogan”) about a “drug-free world”. The UNGASS 2016 outcome document to be adopted the next day is full of talk about this same, drug-free world, 18 years on.

Dunne, a genial and effective chair, diplomatically observes the “balance between traditional and newer approaches to drug policy”.

Towards the end of the session, we see something I’ve been told will be a feature of such discussions: the Russian Derailment. A Russian delegate demands that Maghsoudi tell him “one concrete example” of an indicator that could be used to measure drug policy outcomes. She points out the ICSDP has distributed an open letter listing many such indicator He responds by virtually calling her a silly little girl, telling her he can read and demanding she personally “just tell me one”.

Ok, she says: “Counting overdose deaths.”

The side events continue through the day. At one focusing on the death penalty for drug offences (something the outcome document controversially fails to condemn), Canadian Rick Lines, Executive Director of Harm Reduction International, speaks of the half-dozen countries who execute their people for drug offences as “a very extreme fringe of the international community”.

Next door, the Civil Society Forum is taking place in a room far too small for all those who want to participate. It’s hot and it stinks, and some delegates are already beginning to think it’s no accident.

Later, in another crowded room, there is more discussion about coherence with UN goals. Pithaya Jinawat, Director- General of the Department of Rights and Liberties Protection at Thailand’s Ministry of Justice, offers a PowerPoint presentation apparently transported from the 1990s but speaks with surprising passion about the human rights impacts of his own country’s drug laws. Kathy-Ann Brown, Jamaica’s Deputy Solicitor-General, is even more blunt, unapologetically sprinkling her speech with the words “spliff” and “ganja”.

This meeting has been organised by the agency that authored the SDGs, the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). The UNDP and its SGDs will hover over the week as a kind of philosophical presence, albeit one frustrated by the processes of the UN itself.

The Minister slams the failure to reject the death penalty and calls for “boldness” in responding to the imperatives of drug policy, even suggesting that the Psychoactive Substances Act offers a template for a regulated market. The words are fine, but like the Mexicans, the New Zealanders make a mental note about looking for actions to back them up.

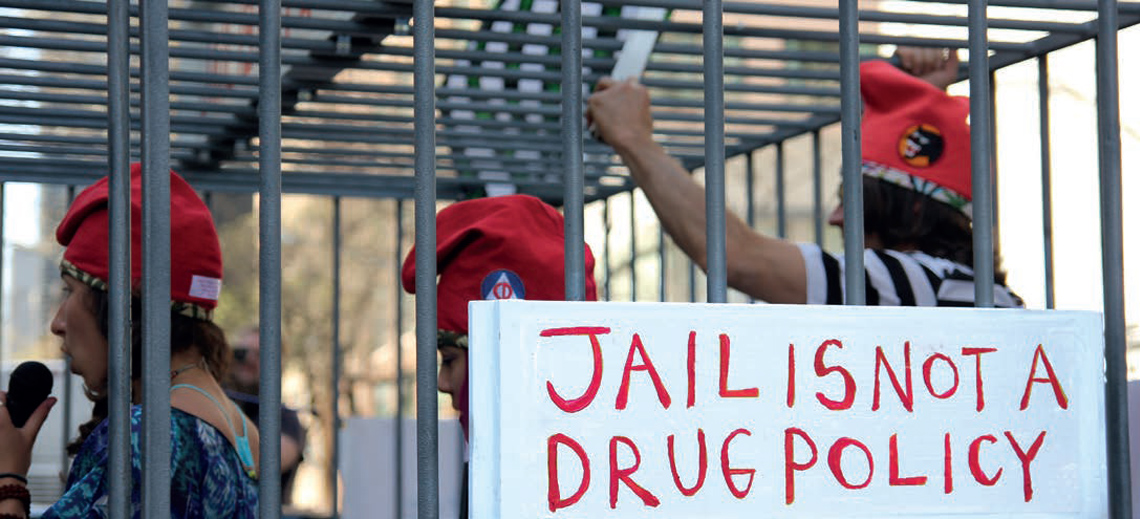

The next morning, day one of UNGASS proper, a group from the Drug Policy Alliance (DPA) is making a small, colourful statement across the road from the UN grounds. Volunteers have dressed up in 1920s garb and are handing out a mock newspaper called The Prohibition Times, a reprint of an open letter to UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon, urging him to “set the stage for real reform of global drug control policy”. The 1,000 signatories include a host of former national leaders and a dozen leading New Zealanders.

While talking to them, someone runs over and reports that UNGASS delegates who have accepted copies of The Prohibition Times are having them confiscated by security guards at the UN gate. It might only be a mock newspaper, but it’s an absurd infringement of the freedom of any press.

The DPA’s Communications Director asks me if I’m prepared to take in some copies for them. Of course, I say – I’m a journalist, after all – and stuff in as many copies as my satchel will fit and zip it up. As I enter, the guards are still taking copies out of the hands of bemused delegates.

Inside, the level four gallery of the General Assembly is full, and I’m directed to an overflow room with video screens, which turns out to be a better place to track the opening proceedings. Sanho Tree, Director of the Drug Policy Project at the Institute of Policy Studies, arrives and sits next to me. He’s late from queuing for his day pass for the UN grounds. I give him a copy of The Prohibition Times.

UN Deputy Secretary-General Jan Eliasson gives a speech urging everyone to get along, even though “some aspects of the drug agenda are sensitive and controversial”.

He talks up the human rights language and references to “proportionality” in sentencing in the text of the outcome document, which “means, in our view, refraining from the death penalty”.

The SDGs get more airtime as “a new tool in our hands, which we must use”. UN Office of Drugs and Crime Chief

Yury Fedotov highlights the document’s language indicating that “drug policy must put people first” but largely defends the orthodoxy. Werner Sipp, President of the International Narcotics Control Board (INCB), is more interesting, allowing for “some flexibility” in the way states interpret the

UN drug conventions but declaring that “flexibility has limits – it does not extend to any non-medical use of drugs”.

In the hours that follow, Sipp’s warning will be applauded by both prohibitionists (for obvious reasons) and reformers, who hear it as saying that the US and others can’t pretend they’re staying within the conventions and must reform them if they want to legalise marijuana. He slams militarised drug control but concludes “neither is it necessary to seek so-called new approaches to the problem. We don’t need new approaches.”

It comes time for member states to speak to the motion to accept the outcome document. Switzerland, Brazil and Costa Rica all slam the absence of a rejection of the death penalty. After all the foregoing talk about “balance”, “consensus” and “integrated” and “friendly” nations, it appears they are endorsing the consensus document only grudgingly and as a first step to real change.

By contrast, Indonesia’s speaker talks up the “sovereign right” of countries to choose capital punishment, noting that China, Singapore, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia and Iran all wished to have their names attached to his statement on the matter.

World Health Organization Director Margaret Chan gives a confusing and disappointing address, banging on about the brave new approaches of her country, Hong Kong, which turn out to consist largely of adopting methadone substitution 30 years after countries like New Zealand.

But Mexican President Enrique Peña Nieto gives the speech of the day – passionate, focused and practical. It’s all the more remarkable given that he’d cancelled his appearance a few days before in what was either a rejection of the UNGASS process or a sign that he just didn’t care that much.

He declares that “Mexico has paid too high a price” under the drug war, which has “not reduced production, trafficking or consumption of drugs” since it began in the 1970s. He explicitly endorses medical cannabis and winds up with what sounds like a call for a regulated drug market.

Later, I’ll speak with Mexican journalist Lisa Marie Sanchez, who has also been surprised by the speech: “Now, we have to hold him to it.”

And the call for a regulated market?

“I’m not he sure he understands what he said there.”

My DPA contact isn’t responding to messages and the stack of The Prohibition Times is weighing heavy. Eventually, I do a Google image search on her name and just walk around looking for her. Happily, it doesn’t take too long to find her and execute the handover.

Over lunch, the team from the Hungarian advocacy group Drugreporter offer to lead me to the media liaison office, which proves to be another mean little space. There is no media centre as such, but we need to come here so one of the casual twentysomethings on staff can walk us back to the meeting room where one of the roundtables will take place. But we’ve barely arrived when word comes through that Peter Dunne’s slot at the General Assembly has come up.

Along with a group of NGO delegates, including Steve Rolles of Transform, I race around looking for a way to the General Assembly viewing gallery. Eventually, we’re literally led up the back stairs in time for Dunne’s speech.

The speech itself is well received in the gallery. The Minister slams the failure to reject the death penalty and calls for “boldness” in responding to the imperatives of drug policy, even suggesting that the Psychoactive Substances Act offers a template for a regulated market. The words are fine, but like the Mexicans, the New Zealanders make a mental note about looking for actions to back them up.

——

My Wednesday is largely given over to shooting TV interviews. New Zealand’s Permanent Mission has kindly given us the use of its boardroom for the purpose, and we shuttle through a series of guests,

including Mäori public health worker Papa Nahi and Tuari Potiki, Chair of the New Zealand Drug Foundation, who both talk about how UNGASS, for them, has been primarily about forging contacts with other indigenous people in search of what Tuari describes as “our own solutions”.

Kathy-Ann Brown is unable to join us at the last moment but sends over several others from the Jamaican delegation, including Ras Iya V, a Rastafarian who has been representing ganja growers and users for nearly four decades. Until Jamaica reformed its laws late last year, decriminalising personal possession and allowing for medical and religious use, his faith made him an outcast. Now, he’s on the board of Jamaica’s Cannabis Licensing Authority and has been invited to the UN by his own government.

“Rastafari and the government had always been basically at war,” he explains. “Our rights have continually been violated – the rights to freedom of belief and freedom of expression. And marijuana, being a part of our culture, was used as a gateway to carry out oppression, tyranny and brutality on the Rastafari community. I wouldn’t have conceived of being part of any government delegation going anywhere at any time.” He believes legalisation in US states encouraged the Jamaican Government to reform but says reform was also “a matter of implementing human rights”.

I think we’ve shattered this idea that there’s a global consensus around the War on Drugs, and we’re headed into two different worlds now. Unfortunately, there are people living in the regressive states who are humans.

Sanho Tree

Back at the UN, trouble is brewing. One of the promises of this UNGASS was that NGOs would be able to play a meaningful part in proceedings. But restrictions on access and a complicated and unexpected system of day passes has been shutting out NGO delegates from key parts of the building. Steve Rolles has had the remarkable experience of being denied entry to a session at which he is presenting. A pass had be smuggled out of the room so he could get in.

In part, the restrictions are to do with something else happening at the UN that week: the attendance of various heads of state for the signing of the Paris Declaration on climate change. But it feels as if there is also something more directly political going on. The speculation is that the hardline countries have been angry about the vocal presence of NGO delegates and demanded a crackdown.

It’s the topic of much discussion among the activists, advocates and journalists at the civil society drinks that evening, along with UNDP boss Helen Clark’s chances for the Secretary- General’s job. The civil society people see each other regularly on the policy circuit, and they greet each other warmly. They also party, hard and as I slip out, the bar is still crowded with people raving at each other about process and personality.

Thursday is lockdown day. The streets around the UN are closed off with checkpoints and filled with a striking array of semi-military vehicles. A panoply of different law enforcement officers stand on corners, some armed with machine guns.

Which makes it all the more remarkable that, as I walk away from the UN grounds along a closed-off 47th Street, there’s a whiff of something you smell fairly frequently on the streets of New York City (NYC) now – marijuana.

For years, NYC has made New York the state with the highest rate of marijuana arrests in the country. Pot has been, year after year, the most common reason for arrest in the city. But locals say the NYPD’s attitude to weed changed almost on the day that Colorado legalised in January 2014. In November of that year, at the urging of Mayor Bill De Blasio, the NYPD officially de-prioritised marijuana enforcement. Possession of 25 grams or less would attract only a low-level summons rather than an arrest.

While UNGASS was in progress, Vice.com published a story hailing “the golden age” of selling weed in New York – the few years of only modest legal or social sanction before legalisation proper (and thus the burden of actual regulation) arrived.

The effects of the new regime are not evenly spread – you’re still more likely to get searched and even arrested if you’re black in a poor neighbourhood than white in a wealthy one – but it appears to have improved the relationship between New Yorkers and the force that polices them. But if such pragmatism can be detected within a block of the UN gates, it may be some time coming inside the gates.

I’m heading out to fetch our cameraman so I can talk him through a checkpoint to shoot an interview with the UNDP’s Tenu Afavia, a strikingly articulate man who had a significant hand in UNDP’s two published contributions to UNGASS.

“We’re encouraged by the mentions of the SDGs at UNGASS,” he says. “Countries are focusing on some of the root causes of people getting involved in the drug trade. We’re encouraged that those countries are looking to move people to the centre of their drug control policies rather than coming up with rules that impact negatively on human development.”

It’s unclear exactly when the second New Zealander to address the General Assembly, Tuari Potiki, will be up, so it seems prudent to head for the gallery and wait. But when I get there, I’m informed my media pass, which I was told in writing was good for the entire week, no longer admits me. I need a day pass. Hilariously, a newly installed security checkpoint denies me entry to the information desk.

I shrug and head for the overflow room. It’s not there any more. A nice lady at the visitor centre checks for me and confirms that there is now no UNGASS overflow room. She suggests I could watch the live stream on my phone. As excellent as the free wi-fi is, that is clearly absurd.

But I realise I can make my way to the media liaison office – bypassing three security stops – via the basement level. On arrival at the second-floor office, the millennial-in-chief sends me up a further level to a desk he says has day passes. They don’t know anything about day passes. A lady walks me to another desk that doesn’t know anything either. Eventually, I make my way to level four the same way as I did on Tuesday. By walking up the damn back stairs.

The three-day stream of addresses to the General Assembly is on its final lap. As it has been every time I’ve checked in, it’s a mixture of deadly dullness and surprising insights. A series of pointless speeches from people whose names start with ‘His Excellency’ is broken by the representative from Cameroon, who talks about his nation’s health and education approach to problems stemming from its status as a “transit country” in the global drug trade. It’s fascinating.

Finally, it’s the turn of the NGO speakers, and eventually, Tuari Potiki is called to the podium. He’s about halfway through his speech when I start quietly crying. At the end of three days marked out by bullshit, his speech is direct, personal, political and deeply moving.

“If there is a war to be fought,” he concludes, addressing the War on Drugs, “and I believe that there is, it should be a war on poverty, on disparity, on dispossession, on the multitude of political and historical factors that have left, and continue to leave, so many people vulnerable and in jeopardy.”

As he finishes, Papa Nahi, who is front and centre in the gallery, stands and responds with a karanga tautoko. Her voice rings out high over the chamber and, for a few precious seconds, actually interrupts the grind of UN process. I feel proud of my country in a way that’s hard to adequately convey.

–––

I meet up with Sanho Tree, who has been in one of the late side-events, and we go and look over the Hudson River.

“Whatever happens,” he says, “I think we’ve shattered this idea that there’s a global consensus around the War on Drugs, and we’re headed into two different worlds now. Unfortunately, there are people living in the regressive states who are humans.”

But if no one believes in the vaunted consensus, is UNGASS’s failure in some sense its victory?

“I think there’s a lot of truth in that. We can’t go on with this farce. I’ve been working on this issue since the 1998 UNGASS, and I’ve seen more change in the past three or four years than in the previous 15 years combined. I think the regressive states are hearing that their days are numbered in terms of how long they can get away with this.”

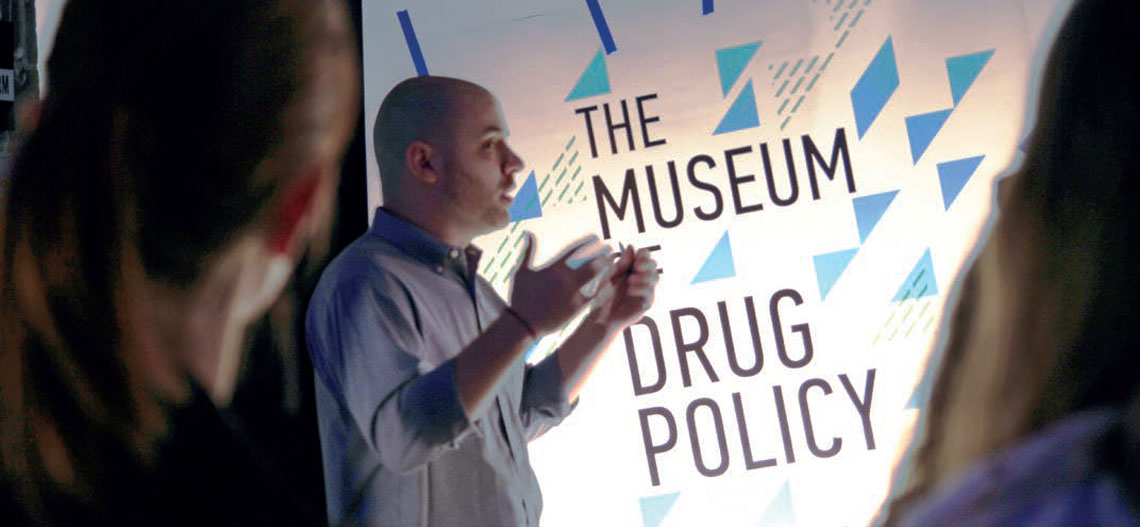

We walk to the pop-up drug policy museum sponsored by the Open Societies Foundation, where there is a restrained party in progress. Eugene Jarecki, director of the stunning drug-war documentary The House I Live In, takes the stage to speak.

“Ten years ago,” he tells the crowd, “I could not have imagined that the drug war would have become so desperately embarrassing to the United States, that we could have gatherings like this where we could truly look at this thing and begin to see the end of it.”

Later, I join several of the other New Zealanders for a quiet drink at my hotel’s rooftop bar. Tuari, still drug and alcohol free after 27 years, is among them. The emotional impact of his speech lingers over us all, and I embrace the man I met only a week ago. And until the barman calls time, we mull over a week in which consensus has meant dissent, failure has been victory and the world has begun to change, for some.

Recent news

Beyond the bottle: Paddy, Guyon, and Lotta on life after alcohol

Well-known NZers share what it's like to live without alcohol in a culture that celebrates it at every turn

Funding boost and significant shift needed for health-based approach to drugs

A new paper sets out the Drug Foundation's vision for a health-based approach to drug harm

Expert Pharmac committee recommends funding for overdose reversal nasal spray

The expert committee has said funding for naloxone in the community should be a high priority