Opinion: Hurt people hurt people

Young people are often on the fringe of policy discourse, but JustSpeak, a youth-led organisation, has forged a strong voice on justice and corrections issues. Here, JustSpeak explains their youthful perspective on New Zealand’s justice system and asks whether positive progress is possible.

Hurt people hurt people. It’s an unfortunate but unavoidable truth within our criminal justice system, and it is no secret that those who offend are often society’s most vulnerable and damaged. It is particularly hard-hitting when a young person caught in the criminal justice system speaks about being broken beyond repair. It forces us to engage with the two major challenges facing New Zealand’s legal and correctional systems: how do we prevent youth from becoming ‘broken’, and if we fail in this, how do we help them put the pieces back together? These are discussions that attract a range of opinions, some more informed than others. However, very seldom do we hear from the individuals who are affected the most by our decisions – the young people of New Zealand.

JustSpeak is an organisation committed to redressing this imbalance by contributing a young, informed and passionate voice to the discussion. JustSpeak is a non-partisan network of young people speaking to and speaking up for a new generation of thinkers who want change in our criminal justice system. In order to achieve a more just Aotearoa,

JustSpeak believes that we need to cultivate a transparent, evidence and experience-based public discourse on criminal justice. JustSpeak volunteers are working actively within our communities, at our policy tables and everywhere in between with the belief that New Zealand’s justice system has a lot of strengths, but it is time that we engage with its challenges.

New Zealand is an exceptionally punitive country and has one of the highest rates of per capita imprisonment in the OECD; 194 prisoners per 100,000 people, compared to Australia’s 130 and Canada’s 114. While this statistic may be greeted with joy by the average radio talk-back caller, our obscenely high incarceration levels should be a source of national shame. Why? Because sending people to prison is a very crude tool for reforming behaviour. A wealth of research shows that imprisonment has little or no deterrent effect on would-be offenders and is no more successful at addressing the underlying causes and motivations of offending than community-based interventions.

Justice Minister Judith Collins recently stated that “a key to reducing crime is to stop young people entering the court and justice system in the first place”. So how is this currently done? When a young person is apprehended for an offence, Police have a number of resolutions available to them, including official warnings, Youth Aid, Family Group Conferences or prosecution. Prosecution is intended for only the most severe cases. However, statistics recently released by the New Zealand Police indicate a slightly different reality about the way in which Police discretion is being used.

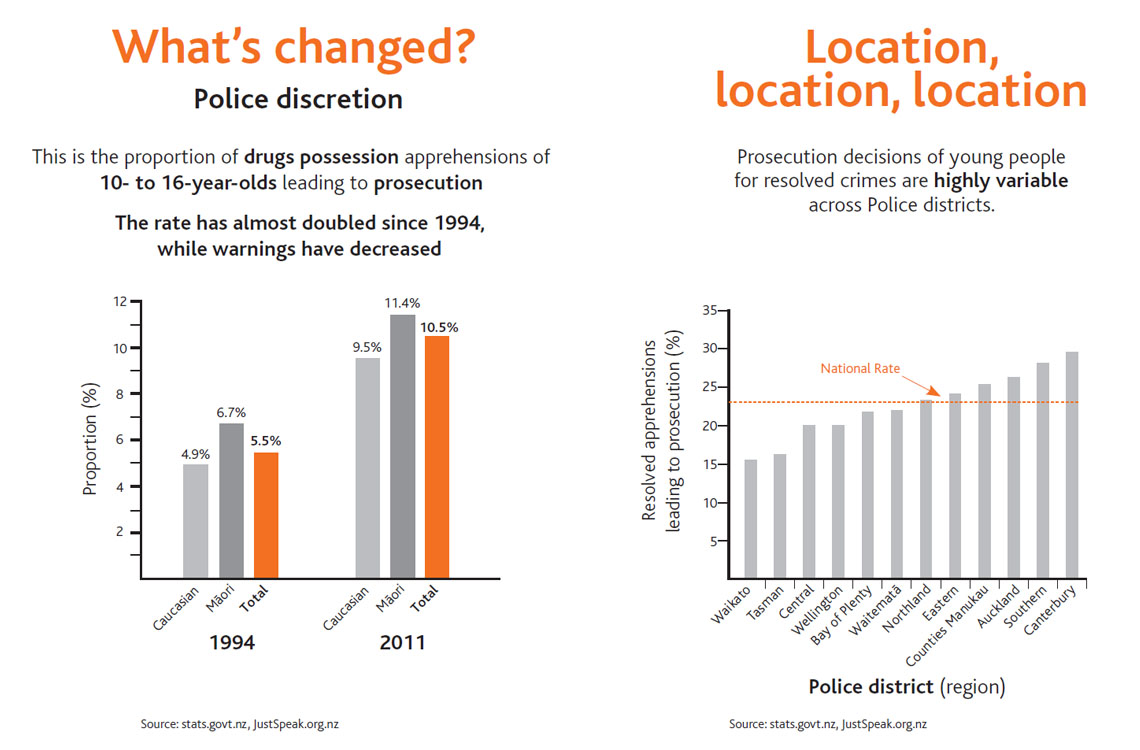

In 2012, youth apprehensions for illicit drug offences made up 4 percent of total youth apprehensions. Two-thirds of these apprehensions were attributable to drug possession and/or use; a majority of the time, the illicit drug in question was cannabis. While total apprehensions have decreased over time, prosecution rates have not. Close to twice the proportion of young people are being prosecuted for drug possession and/or use when compared to 18 years ago, while the number of warnings being given has dropped by 30 percent. That amounts to an additional 55 young people each year who are faced with a response that is meant to be reserved only for the most serious offences. This action violates one of the basic principles that underpin New Zealand’s correctional rehabilitation system: interventions should correlate with risk level. Not only do more intensive interventions allow young people to associate with higher-risk offenders (one of the main correlates of criminal behaviour), but they can also severely impact on protective factors such as education and family connections. Potential substance abuse issues only further compound these problems.

1. What’s changed? Police discretion . The rate of drug possession apprehensions has almost doubled since 1994, while warnings have decreased. 2. Prosecution decisions of young people for resolved crimes are highly variable across Police districts. - Source: stats.govt.nz, JustSpeak.org.nz

This pattern of increasing reliance on prosecution as a response to youth crime is alarming and directly contradictory to what we know is best for our young people. Studies tell us that many young people going to court or receiving custodial sentences fail to get the help that they need to continue their education and deal with mental health or substance abuse problems. Of the 3,500 young people under the age of 17 who came before the courts in 2011, 80 percent had substance abuse issues. However, between October 2010 and April 2012, judges made only 18 orders for treatment programmes. Harsh penalties do not fix broken people. The appropriateness and efficacy of punitive punishment as a response to youth crime, particularly in relation to possession and use offences, is something that needs to be very closely examined.

But there are certainly some silver linings on this rather dark metaphorical cloud. A number of progressive initiatives are being incorporated into the youth justice sector in New Zealand and are attracting international praise. The diversionary approach that is the main focus of our youth justice system is also one of its biggest successes. While it raises concerns of potential differential treatment (see the infographic on regional prosecution rates released by JustSpeak), any progress made towards reducing the number of youth appearing before the formal court system is progress worth celebrating.

In this vein, a number of novel approaches to the court system have been trialled in New Zealand, largely to successful outcomes. For example, the Christchurch Youth Drug Court (YDC) is an initiative aimed at reducing offending related to alcohol and/or drug dependency amongst young people. Becoming operational in 2002, the YDC aims to facilitate early identification of young offenders with substance abuse problems and targets their needs accordingly. Diversion into this programme is initiated once a potential substance abuse problem is identified in Youth Court, and young people are monitored closely throughout their involvement with the YDC, being released only once they have reached sobriety. The Intensive Monitoring Group (IMG) Court is another specialised court system being developed to target the needs of young offenders. Based on the YDC, the IMG provides therapeutic intervention to young people with moderate to severe mental health needs who are also at a high risk of re-offending. Unbroken, continuous involvement with judges and social workers, as well as intensive monitoring of the youth, is utilised in the hope of improving the outcomes.

While positive progress is being made, the way in which we approach and discuss justice issues in New Zealand needs to change. Change for the good does not necessarily need to be radical. JustSpeak recently advocated in a submission on the Psychoactive Substances Bill for the exclusive use of a diversion system in response to youth substance possession offences. Expanding what is the main strength of our current youth justice system is one step we can make towards a more just New Zealand. Our current justice system most certainly has its challenges, but it’s just as certain that the system can be changed in a positive and progressive way. Some of our young people may be broken, but they most definitely can be fixed.

JustSpeak is a non-partisan network of young people speaking to and speaking up for a new generation of thinkers who want change in our criminal justice system.

Recent news

Beyond the bottle: Paddy, Guyon, and Lotta on life after alcohol

Well-known NZers share what it's like to live without alcohol in a culture that celebrates it at every turn

Funding boost and significant shift needed for health-based approach to drugs

A new paper sets out the Drug Foundation's vision for a health-based approach to drug harm

Expert Pharmac committee recommends funding for overdose reversal nasal spray

The expert committee has said funding for naloxone in the community should be a high priority