Ketamine - what you need to know

Drug monitoring agency High Alert has reported a large increase in the availability of ketamine nationwide over the past 18 months. Customs Department seizures of the drug increased by 150% between 2019 and 2020. And while the quantities involved are still relatively small, they suggest ketamine use is on the rise in New Zealand. Ruth Nichol takes a look at the drug known by a variety of names, including Special K, K and ket.

What is ketamine?

Ketamine is an anaesthetic that has been used by doctors and veterinarians since the 1950s.

It’s used in emergency departments to provide sedation and pain relief during short, painful procedures such as setting a broken bone or stitching up a facial injury. It was famously used in combination with other drugs to sedate the 12 boys who were rescued by divers after being trapped in a cave in Thailand for more than two weeks in 2018.

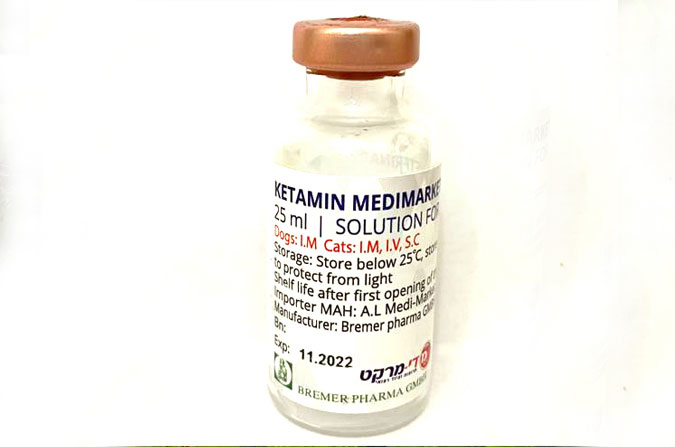

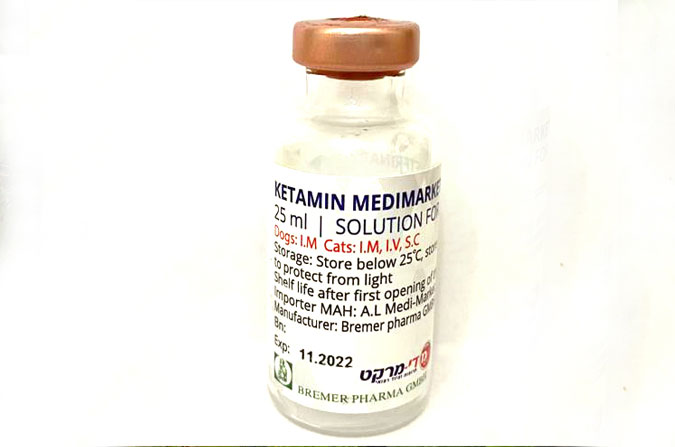

In medical settings ketamine is administered intravenously or intramuscularly in liquid form. Vets use it in a similar way to anaesthetise animals.

How does ketamine work?

Ketamine is a dissociative anaesthetic drug with hallucinogenic properties, which means it acts on chemicals in the brain to produce a sense of detachment from reality. It also provides pain relief and it has an amensiac effect, which helps people forget a painful medical procedure once it has finished.

In some countries, low doses of ketamine are used to treat depression, particularly depression that is resistant to other kinds of treatment. Clinical trials into ketamine’s antidepressant effects are currently being carried out by scientists at the University of Auckland’s School of Pharmacy.

According to Asociate Professor Suresh Muthukumaraswamy who is helping to conduct the trials, the amounts of ketamine involved are very small and administered in a tightly controlled setting.

“People have to come into the clinic to get it and they’re only given about 25mg twice a week, which is a lot less than a recreational user would take.”

How is ketamine used in non-medical settings?

Ketamine arrived on the recreational drug scene in the 1980s. It’s taken in order to achieve a hallucinatory, dream-like state and is known by a variety of names, including Special K, K, ket, kitkat, super k or horse trank.

Ketamine can be swallowed or injected in liquid form. It can also be snorted as a fine white power that is usually made by converting it from a liquid state. Sometimes the powder is smoked with cannabis or tobacco.

It’s also possible to buy ketamine analogues, which are chemically very similar to ketamine but are usually stronger in their effects. Common analogues include deschloroketamine, N-desmethylketamine and Methoxetamine (MXE).

How common is ketamine use?

It’s hard to get figures about ketamine use in New Zealand though until recently it’s thought to have been relatively low.

However, there are indications that ketamine use is on the rise. In May 2021 drug monitoring agency High Alert noted a large increase in the availability of ketamine nationwide. New Zealand Customs Service seizures of ketamine rose 150% from 2019 to2020 – despite COVID-19 restrictions which led to decreases in seizures for most substances.

While the quantities involved are still small – less than 10kg – High Alert says that along with other information received, this increase likely means a large increase in ketamine consumption.

Anecdotal reports suggest that the use of ketamine analogues is also increasing.

What are the potential risks of using ketamine?

The effects of ketamine tend to be more psychological than physical, producing a sense of dissociation that typically last between 15 minutes and an hour.

The effects vary depending on a person’s size and individual metabolism, as well as the dose level. As Ben Birks Ang, the Drug Foundation’s Deputy Executive Director – Programmes, points out, one of the difficulties in using ketamine is that it can be hard to know what concentration the drug is.

“There’s a general risk when you’re buying on the illegal market that the chances of having unexpected experiences are quite high,” he says.

One of the biggest physical risks comes from combining ketamine with another depressant drug – including alcohol – which can cause a dangerous slowing down of breathing and heart rate.

Taking ketamine can cause something called k-hole, where people feel disconnected from or unable to control their own bodies, including the ability to speak and move around easily. Some people take ketamine in order to enter a k-hole, but others find the experience disturbing.

Birks Ang says this makes it particularly important for people to use ketamine in situations where they know the people they are with and they’re in a good state of mind. “Things like the k-hole state can be really distressing not just for the person but also for the people around them.”

Other potential risks from using ketamine include:

- vomiting or feeling nauseous if you eat just before taking it

- a dangerous speeding up of heart rate due to combining ketamine with stimulant drugs such as cocaine and amphetamines.

Ketamine bladder syndrome (k-bladder)

Long-term users of ketamine can develop ketamine bladder syndrome or k-bladder. Symptoms are similar to those of a urinary tract infection, but they do not respond in the same way to antibiotics. Symptoms include difficulty holding in urine and incontinence, and can eventually lead to ulceration in the bladder.

Anyone suffering from k-bladder should stop using ketamine and get treated immediately, to avoid permanent damage to their bladder.

Can you get addicted to ketamine?

Long-term and frequent users can be become addicted to ketamine, though according to Muthukumaraswamy the addictive potential of ketamine is more similar to that of alcohol.

“There is ketamine addiction, but the risks aren’t as high as they are for cocaine and similar kinds of drugs,” he says.

Withdrawing from ketamine is said to be easier than withdrawing from other drugs, though it’s still best done with support.

Will ketamine ever be decriminalised?

There are no moves to decriminalise ketamine in New Zealand, but there are moves afoot in several American states to decriminalise possessing or using ketamine as part of a wider move to decriminalise the use of psychedelic drugs.

A vial of Ketamine for veterinary use, with a concentration of 10mg per ml.

Recent news

Beyond the bottle: Paddy, Guyon, and Lotta on life after alcohol

Well-known NZers share what it's like to live without alcohol in a culture that celebrates it at every turn

Funding boost and significant shift needed for health-based approach to drugs

A new paper sets out the Drug Foundation's vision for a health-based approach to drug harm

Expert Pharmac committee recommends funding for overdose reversal nasal spray

The expert committee has said funding for naloxone in the community should be a high priority