Viewpoints: So should naloxone become more accessible in New Zealand?

In the United States opiates cause thousands of overdose deaths each year. Now Police officers and community members are being equipped with an antidote drug called naloxone to combat what has become a public health crisis. Making naloxone more readily available here would widen the safety net for overdose victims, a vital step if we follow international trends towards rising heroin use. Opponents argue broader access to naloxone could give drug users a false sense of security. So should it become more accessible in New Zealand?

The case for:

IT is a life-saving drug that’s safe, easy to use and affordable. Naloxone hydrochloride (or the brand name Narcan) is an opioid antidote that can immediately reverse a potentially fatal overdose caused by opioids such as morphine, the powerful prescription painkiller oxycodone and the illicit drug heroin. It’s possible that, if given early enough, it could have saved the life of acclaimed American actor Philip Seymour Hoffman, who died of a heroin overdose in February this year.

So it is logical to make naloxone, which can be injected or given as a nasal spray, more widely available in New Zealand so it can be quickly administered in emergency situations where opiate poisoning is suspected. Ambulance paramedics and intensive care paramedics (the more highly trained levels of ambulance staff) already routinely carry the drug and are trained in how and when to inject it into a patient. New Zealand Police are not equipped with naloxone. The argument is that the number of overdoses is too low here to justify the training required for them to be able to administer the drug properly. However, Charles Henderson, national manager of the New Zealand Needle Exchange Programme, warns there are signs that heroin use here is rising and the number of overdoses could rise accordingly.

“Whilst it’s rare, we think we’re seeing increases, and when we consider some of the reports and Customs data around, we think heroin is on the rise.”

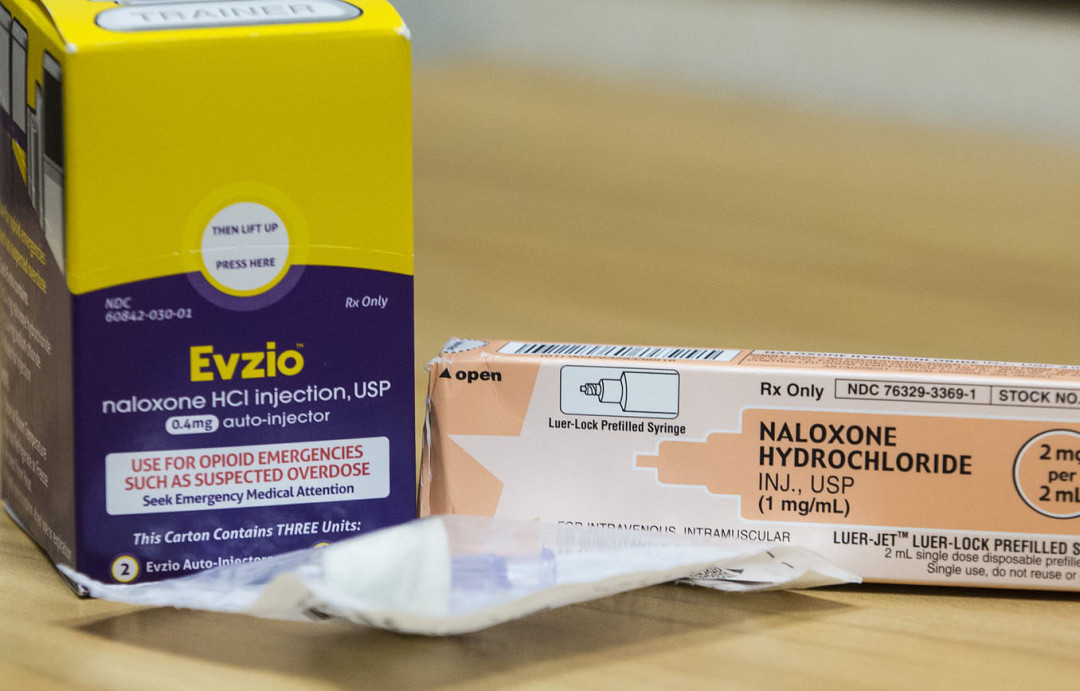

In the United States, on average, 110 people die each day from overdoses, and more than half of these fatalities involve opioids such as heroin and prescription painkillers. Heroin overdose deaths increased by a staggering 45 percent between 2006 and 2010. In July, US Attorney-General Eric Holder called for more law enforcement agencies to supply their personnel with naloxone, saying opioid addiction was a public health crisis. In New York City, state funding of US$1.2 million has been provided for 20,000 officers to begin carrying naloxone kits this year, following similar initiatives in many other states. The US Food and Drug Administration also fast-tracked approval of a new device called Evzio, which delivers a dose of naloxone through a hand-held injector. When activated, it gives spoken instructions to the user on how to inject the drug in an emergency.

While the number of opioid overdoses in New Zealand is currently low compared to other countries including the United States and Australia, there is a strong case for naloxone to be made more accessible as part of a harm-reduction approach. This might not necessarily be through equipping Police officers and other emergency services staff with naloxone, but instead could be done through community-based programmes. Health clinics could be set up in a working partnership with a needle exchange where GPs could prescribe the drug to those deemed to be at higher risk. Naloxone kits could also be issued to vulnerable groups such as recently released prisoners.

While it’s positive that ambulance paramedics carry the overdose antidote, sometimes they might not get to the scene quickly enough to administer naloxone at the optimum time. The other difficulty is that people are sometimes reluctant to call emergency services to report an overdose, because in doing so, they may be putting themselves at risk of facing drugs charges.

If family members or caregivers of an injecting drug user had naloxone close to hand, perhaps in an easy to use form like Evzio, they could use it as a first-aid response to overdose. Opioid poisoning victims quickly lose consciousness, so receiving naloxone immediately rather than waiting for emergency services boosts their chances of survival.

Naloxone, which is on the World Health Organization’s Model List of Essential Medicines, is unlikely to cause harm even if given in the wrong circumstances. Making it more readily available to those who might need it – either through the peers of drug users or their family members and caregivers – would save lives.

The case against:

THERE’S an important difference between New Zealand and other countries such as the United States and Britain where moves are under way to equip Police officers with naloxone. Our rates of opioid overdose are extremely low.

The reason for this is that heroin is now rare in New Zealand and injected drugs are nearly all diverted pharmaceuticals, which means users have a more reliable idea of what dose they are taking. Heroin has a variable strength and purity, which makes it more likely to cause an accidental overdose.

Recently released prisoners who have been drug users are at higher risk of overdose because their tolerance is lower, but Jeremy McMinn, co-chair of the National Organisation of Opioid Providers says, in most cases, Kiwi prisoners are allowed to remain on methadone or other opioid substitutes while they are serving their sentence, which helps protect them after they are released.

While it might seem like a positive step to arm those likely to be on the scene with an antidote to an overdose among one of their peers or a family member, there could be an unintended consequence from widening availability of naloxone; people could become less cautious about their drug use because they know life-saving treatment is close at hand.

“They might think they have this safety net of having naloxone right by them. What’s lacking is research to reassure us that emergency kits given to people using opioids actually increase safety across the board. They might, in fact, increase risky use,” McMinn says.

Naloxone is carried routinely in ambulances staffed by several hundred paramedics and intensive care paramedics around the country, and St John Medical Director Tony Smith says they would be sent in all cases where opioid overdose was suspected.

“The requirement for naloxone is very low. I don’t have any hard data, but opiate poisoning requiring an ambulance is a relatively unusual event. The incidence is so low in New Zealand that we don’t think it’s worth extending this [naloxone training] beyond the paramedic and intensive care paramedic staff.”

Police Association President Greg O’Connor says the heroin scene is New Zealand today is very different now to what it was like in the 1970s when the Mr Asia drug syndicate was active. He remembers once encountering two heroin overdoses in one shift when he was a Police officer back then. The number of overdoses currently did not justify the training and cost required for Police to be equipped with naloxone, and it was not something he would advocate for at this stage.

Perhaps surprisingly, given the cultural similarities between Australia and New Zealand, so far New Zealand has not followed the trend of rising numbers of opioid-related overdoses happening across the Tasman. If the situation changes, perhaps access to naloxone should be reviewed, but at present, the cost and time involved in training and equipping more emergency personnel or setting up healthcare-based community schemes for distributing the drug more widely, are not warranted and could be better spent on more urgent priorities.

Recent news

Beyond the bottle: Paddy, Guyon, and Lotta on life after alcohol

Well-known NZers share what it's like to live without alcohol in a culture that celebrates it at every turn

Funding boost and significant shift needed for health-based approach to drugs

A new paper sets out the Drug Foundation's vision for a health-based approach to drug harm

Expert Pharmac committee recommends funding for overdose reversal nasal spray

The expert committee has said funding for naloxone in the community should be a high priority