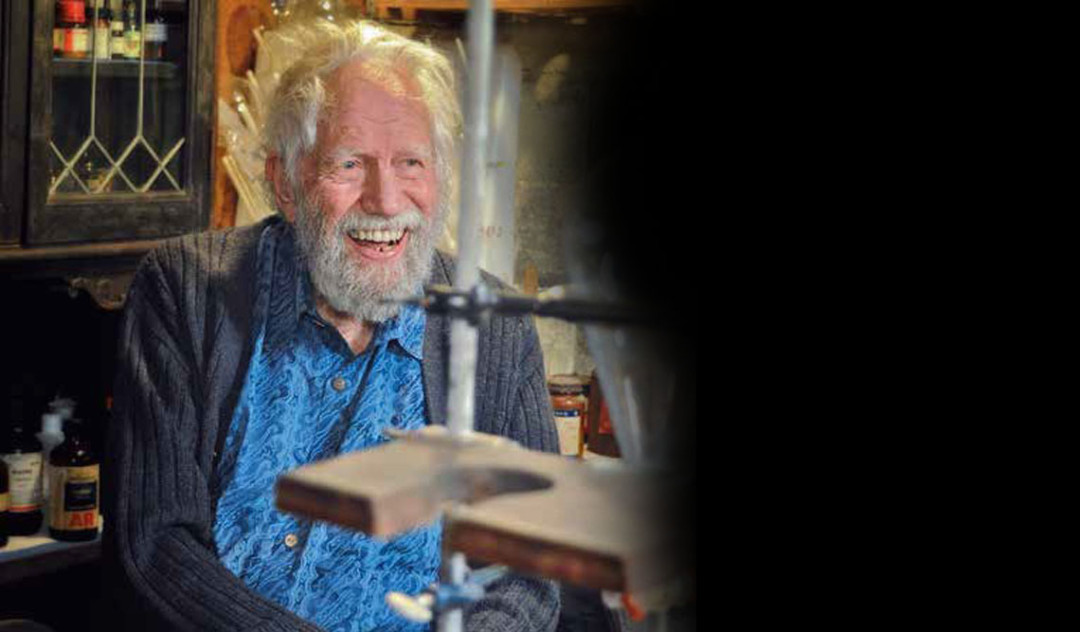

Shulgin was known to many as the “Godfather of ecstasy”

Alexander “Sasha” Shulgin was born on 17 June 1925 and died, aged 88, at home in California on 2 June 2014. As he died, the sounds of his grandchildren’s laughter rang through the house and combined with the chants of the ancient Buddhist Heart Mantra, which hails the dying’s departing soul. You could do worse.

Shulgin was known to many as the “Godfather of ecstasy”, famed for resurrecting the long-forgotten recipe for 3,4- methylenedioxy-Nmethylamphetamine, MDMA or simply ‘ecstasy’ from the archives of German pharmaceutical firm Merck in the 1960s.

Shulgin’s destiny, and that of this drug, are intertwined in the most implausible of ways. MDMA was originally designed by Merck in 1912 in a bid to produce a blood-clotting agent. However, Shulgin created a new and easier synthesis and inadvertently triggered the dance-drug culture that endures to this day, with tonnes of the drug consumed worldwide.

He was tipped off to the drug’s extraordinary qualities, its ability to inspire empathy and self-analysis, by a student in the late 1960s. He made and took the drug for the first time in 1978 and was awestruck by its qualities. The drug spread, like vast ripples on an infinite pond, from these experimental psychotherapeutic circles to the dance floors and music festivals of the world.

He was one of the 20th century’s foremost scientists, a brilliant and fearless pioneer who synthesised, self-tested and recorded the effects of hundreds of new psychedelic drugs. He published his work in two books, PIHKAL, a chemical love story and TIHKAL, the continuation, which detail the synthesis of hundreds of tryptamines and phenethylamines and remain classics of clandestine chemistry.

“I am completely convinced that there is a wealth of information built into us, with miles of intuitive knowledge tucked away in the genetic material of every one of our cells,” he wrote. “The psychedelic drugs allow exploration of this interior world and insights into its nature.”

He was a mass of entirely logical contradictions. Here was a renegade chemist who worked for the DEA. He was an expert witness in drugs cases who could be found in the late 1990s lecturing on the finer points of phenethylamine synthesis in the shade of Mayan pyramids, joking that the CIA was watching. In later years, he would walk around at Las Vegas’s anarchic annual Burning Man festival, his face a knot of confusion and delight.

In 1978, he met his wife Ann, who was born in Wellington, New Zealand. They married in 1981. She used his creations in her therapeutic practice, and together, they were a charming, eccentric couple, bonded by love and respect for each other’s chosen disciplines. Friends describe their partnership as a perfect union, and their warmth and generosity to researchers, journalists and the merely curious was legendary.

Dr Dave Nichols, a renowned biochemist who published several key papers with Shulgin, spoke about one of his more memorable visits to the Shulgin family home.

“[It] was some time after the Rubik’s cube craze hit. Sasha had worked out a clever, non-fail formula to solve it. “We had dinner and had been chatting for some hours, and we had been drinking red wine. He brought out the Rubik’s cube and began to describe and show me his system for solving it.

“I rarely drink alcohol and had probably had at least four or five glasses in me. Even so, Sasha described with great patience, how to solve the cube, and even wrote out instructions for me using red and blue coloured pencils. After several false starts, I finally went through it, with his tutelage, and solved the cube. Somewhere, lost and buried in my reams of stacked papers, is a small notepaper with red and blue lines on it illustrating the stepwise process for solving Rubik’s cube that Sasha had solved!”

Shulgin described himself as a toolmaker, and the job he set out to do was to give people access to unexplored corners of their own minds.

“Our generation is the first, ever, to have made the search for self-awareness a crime, if it is done with the use of plants or chemical compounds as the means of opening the psychic doors,” he wrote in PIHKAL. “But the urge to become aware is always present, and it increases in intensity as one grows older.”

Shulgin was born in Berkeley, California, in 1925 to a Russian-emigrant father who became a schoolteacher. He studied organic chemistry at Harvard but dropped out in 1943 to join the US Navy. Arguably, the most influential drug experience of his life happened during this period. It was a few small grains of powder given to him by a nurse.

While at sea, he suffered a serious thumb infection that required surgery. Handed a glass of juice by a nurse, he spotted some undissolved solids at the bottom of the glass, assumed it was a sedative and fell unconscious. It was actually sugar; the placebo effect had knocked him clean out. This was his first consideration of the interface between mind and body and drugs that would come to shape his life.

On leaving the Navy, Shulgin returned to California where he earned a PhD in biochemistry. He then worked at the University of California before working at Bio-Rad labs and later at Dow Chemicals. There, he invented a new pesticide that was so profitable for the firm he was given free rein in its labs.

Fascinated by his experiences in the late 1950s with mescaline, he began to produce variants – new psychedelic drugs – in Dow’s labs. He left the firm in 1965 and built his home laboratory, an alchemist’s lair with a Rachmaninov soundtrack. Here, he was free to pursue his interests as he saw fit, helped along by a DEA licence to produce illegal drugs, granted in exchange for his help as an expert witness in trials.

Shulgin created many hundreds of drugs and then tested them at home with friends, recording the experiences meticulously. He was anything but a hedonist, even though the substances he made elicited joy in millions.

Matthew Collin, the journalist and historian whose book Altered State remains the definitive record of the emergence of MDMA as a world conquering compound, says Shulgin’s legacy must be viewed in context.

“Shulgin had a massive impact on popular culture, but it’s unclear how much he really understood it. He envisaged his beloved ‘materials’ being taken in benign, controlled settings, which are a long way from the average rave full of wilful hedonists looking for the next buzz.”

Shulgin’s career spanned the 1960s’ psychedelic explosion right through the rebirth of MDMA, and his legacy can be seen in the modern-day emergence of novel psychoactive substances – drugs that skirt national and international laws through deliberate molecular manipulation.

He was the counterculture’s eminence grise, a figurehead for a generation who rejected the irrationality of drug prohibition and a scientist who hit the bullseye of targets others didn’t even know existed. He never made a penny from his creations, while many have retired early on the illicit profits made thanks to his work.

Shulgin had a stroke in 2010 and was supported in his later years by the generosity of hundreds of well-wishers.

His first marriage, to Nina Shulgin, ended when she died in 1977. Their son, Theodore Shulgin, died in 2011. He is survived by Ann and four stepchildren.

As he died, these words were chanted at his bedside.

Gate, gate

Gone, gone

Para gate

Gone beyond

Parasamgate

Gone way beyond

Bodhi Svaha!

Hail the goer!

Mike Power is a UK-based writer and author of Drugs 2.0: The web revolution that's changing the way the world gets high

Recent news

Beyond the bottle: Paddy, Guyon, and Lotta on life after alcohol

Well-known NZers share what it's like to live without alcohol in a culture that celebrates it at every turn

Funding boost and significant shift needed for health-based approach to drugs

A new paper sets out the Drug Foundation's vision for a health-based approach to drug harm

Expert Pharmac committee recommends funding for overdose reversal nasal spray

The expert committee has said funding for naloxone in the community should be a high priority