Street value: The Dutch MDMA pop-up shop sparking conversations about drugs

In the picturesque Dutch city of Utrecht, on a bustling cobbled pedestrian street in the medieval centre, an unassuming pop-up shop sits among canals and eateries. A sign outside says ‘MDMA for sale’.

The pop-up ‘XTC shop’ is, in fact, an exhibition by Poppi Drugsmuseum, a Mainline Foundation initiative.

The Mainline Foundation is the Dutch equivalent of the NZ Drug Foundation. For more than thirty years, they have been strong harm reduction advocates, working to improve the rights and health outcomes of people who use drugs.

Starting in mid-July and concluding today, the exhibition aimed to spark public conversation around the regulated supply and sale of MDMA in Holland. Rather than focussing on the polarised yes/no debate, the exhibition explores the practicalities of what a regulated market might look like.

Managing Director of Mainline, Machteld (Mac) Busz, says the response from the public to the exhibition had been “curious and overall, quite positive.”

MDMA, also known as ‘e’ or ecstasy, is a psychoactive stimulant that comes in powder or pressed pill form and enjoys enormous popularity across the Western world. Often called the ‘love drug’, ecstasy makes many users feel euphoric and prone to touching or hugging those around them.

MDMA regulation is a pertinent issue for the Netherlands. Unlike with cannabis and psilocybin ‘truffles’, ecstasy cannot be purchased from retailers. Instead, it is manufactured primarily by criminal gangs with no quality or safety controls, and with toxic chemical by-products disposed of in local waterways.

The Netherlands is the number one ecstasy producing nation in the world. The estimated annual street value of MDMA produced in Holland runs to multiple billions of Euros.

Against this backdrop, Mainline is advocating for the legalisation and regulation of MDMA production and supply.

“We see a lot of crime related to the production of ecstasy,” says Busz.” We also see a lot of environmental waste. In an unregulated sector, of course there are no rules about how you dump your waste.”

In a regulated market, by comparison, the government could ensure the safe and sustainable production and distribution of MDMA, reducing the negative societal outcomes.

MDMA’s status in Dutch society

At present, the Dutch government spends hundreds of millions of Euros combatting the production and trade of MDMA.

That’s despite a recent survey showing that nearly 10%, or 1.7million Dutch people, have tried MDMA at some point in their lives and around 370,000 people will use it in a given year.

The exhibition also cites a recent Ipsos survey which showed more than half of those below the age of 54 are in favour of a “more realistic policy” for the production and sale of ecstasy.

In 2020, Mainline joined a chorus of Dutch scientists and experts who advocate for drug policy based on “facts, rather than emotion and morality.” The group of 18 independent experts, with backgrounds in health, social services and law enforcement, recommended that the supply and production of MDMA be regulated. The group said this would reduce social and physical harms, MDMA-related organised crime and environmental damage, increase national revenues and ensure the quality of MDMA products for the many Dutch who consume it.

Like in the Netherlands, MDMA is one of the most popular drugs in New Zealand. Based on wastewater testing results from 2019, it is estimated that around 378 kgs of MDMA are consumed in NZ each year, equivalent to some 3.78 million doses. NZ polling shows that 61% of people support removing penalties for general drug use and support putting in place more support for education and treatment.

Compared to New Zealand, however, the Netherlands has a far more liberal culture surrounding illicit substances. While it is officially against the law to produce, sell or possess illicit drugs, the reality is very different. The Dutch approach to multiple substances, where a law is on the books but not enforced, is referred to as gedoogbeleid. Roughly translated, it means ‘illegal but not illegal’ or more simply ‘tolerance.’

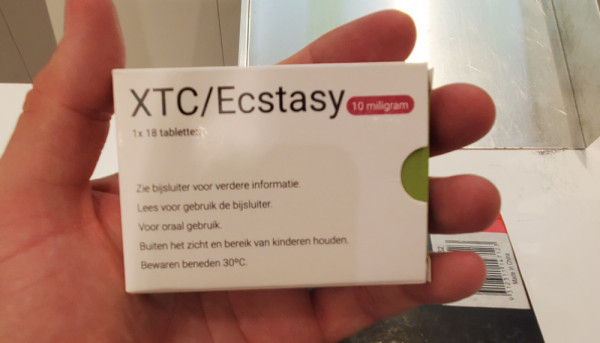

A hypothetical ‘MDMA pharmacy’ that would provide people with MDMA under controlled conditions. This is the preferred model for Mainline Foundation.

Navigating the XTC shop

Visitors to the shop navigate their way through several rooms, each exploring a different potential model of MDMA regulation. Peppered between colourful MDMA pills and paraphernalia are facts and health advice about the drug. You are encouraged to take “MDMA” packages from the shop that contain candy in the shape of pressed ecstasy tablets.

Busz admits Mainline took an intentionally provocative approach to promote the exhibition; a sign on the shop’s street window says in Dutch, “Get your pill, it will make you feel good.”

Such marketing prompted concerns from some of the shop’s neighbouring businesses and caused others offence. But does this exhibition glamourise MDMA?

“We do it, of course, to get people to pay attention to the discussion,” she says.

She said that people entered the shop with a range of emotions; some were really angry; some came in wanting to buy.

“By using art and being a bit provocative, it’s a mirror for how we deal with other substances in society. There is a risk that at first glance, people see [the exhibition] as glamourising MDMA. I hope that once they enter and see how seriously and scientifically grounded we are, this impression will quickly go away.”

“What we try to show is that in a regulated system, you don’t want marketing and promotion for drugs,” Busz says. “Why can you still market alcohol in the public space?” she asks. “That is really something that I find unbelievable.”

In each room, visitors can watch short video clips on iPads and are prompted to answer questions such as what age someone should be in order to buy MDMA, whether they should be required to provide ID and the amount that someone should be permitted to buy at once. That anonymised information then becomes a valuable dataset for Mainline in the ongoing public discussion surrounding drug regulation.

Different regulatory models demonstrated in the exhibition range from one in which there would be no limits on marketing, with people able to buy unlimited amounts from vending machines, through to a pharmacy-type approach where there would be limits on purchases, a ban on marketing, and a requirement for MDMA vendors to provide health advice to consumers.

The latter option is Mainline’s preference and the most aligned with a harm reduction approach.

“[You could] give health advice or safe-use advice, control how many pills they can buy, age restrictions, whether people can buy for others. You can have conversations with your customer, so they are aware the risks involved,” Busz says.

Using MDMA regulation to facilitate broader drug discussions

Because MDMA is primarily used recreationally by middle-class people, Busz explains that the topic of regulation is far removed from many of the people Mainline aims to serve: people who use drugs on the margins of society.

“The real losers of the system of prohibition in the Netherlands are not people who use MDMA at parties. They get away with it. At the most, they may get a fine, but won’t get a criminal record.”

MDMA regulation does serve as a useful entry point, however, to get people thinking about drug prohibition and who is most affected by it.

“Underlying the [MDMA] system is crime, the black market for drugs – the people, and in particular, the young people who are being drawn to drug production, drug trafficking, all the odd jobs within the system of the drug trades. They need different perspectives,” she says.

“[We want to] address the issues that underly the current system… where some people feel that the only chance they have in life, is a career in drugs.”

Mainline is also focussed on the people whose dependence on drugs impacts their lives, employment and housing security."

“For us, drugs should be dealt with in the public health system– it’s not an issue that you can solve by creating a huge justice apparatus machine.”

The political issue of MDMA legalisation

In Dutch Parliament, several parties, including one of the current ruling coalition, support the regulation of MDMA and other psychedelic substances. The idea pops up occasionally in public discourse due to issues associated with crime.

But Busz says that few in Parliament are willing to “stick their necks out on this.”

She says that many politicians fear that if Netherlands became the lone country to regulate MDMA, bucking international conventions, it could become a narco state where “everyone and their uncle comes to produce ecstasy.”

At present, the national legalisation and regulation of MDMA in the Netherlands is unlikely to happen anytime soon. However, the ruling coalition for the city of Amsterdam have backed the idea of the city running a pilot study for the regulated supply of MDMA.

What comes next?

Busz says she hopes that by engaging the public in conversations like this, people will slowly discover that there are much bigger, more complicated, but also much more urgent issues in the drug space than recreational MDMA.

“That’s our underlying motivation,” she says.

Long-term, Mainline Foundation aims to turn the Poppi Drugsmuseum into a profit-making venture. The goal would be to reinvest any profits they generate into their harm reduction work, magnifying Mainline's reach.

The Utrecht XTC exhibition had its final day on 29 September. To find out more about Mainline Foundation, visit their website.

Recent news

Beyond the bottle: Paddy, Guyon, and Lotta on life after alcohol

Well-known NZers share what it's like to live without alcohol in a culture that celebrates it at every turn

Funding boost and significant shift needed for health-based approach to drugs

A new paper sets out the Drug Foundation's vision for a health-based approach to drug harm

Expert Pharmac committee recommends funding for overdose reversal nasal spray

The expert committee has said funding for naloxone in the community should be a high priority