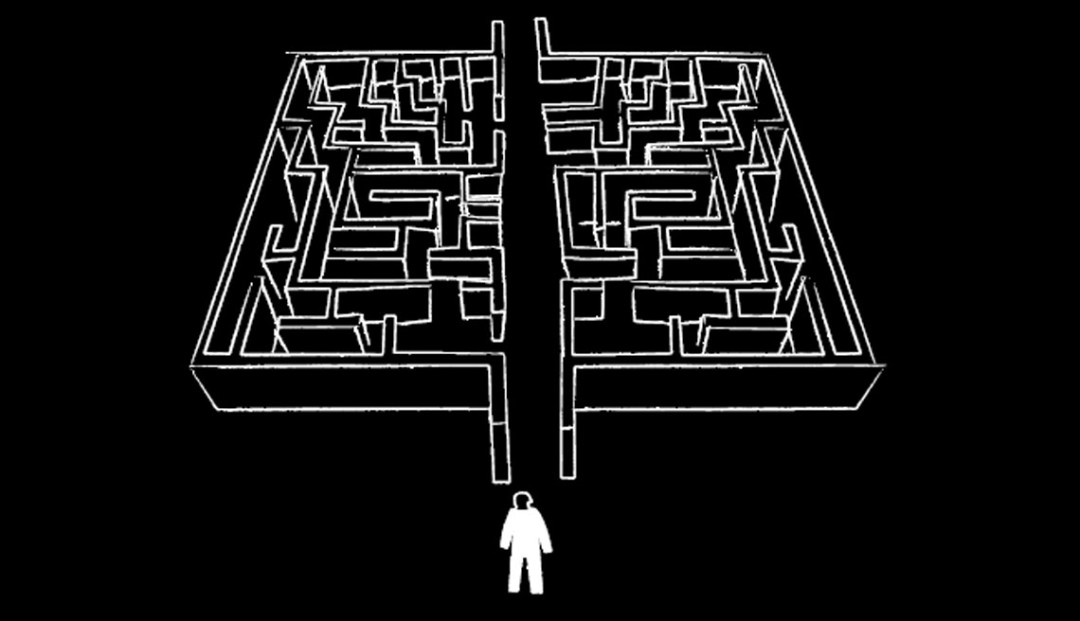

Through the maze - healthy drug law reform

Our Misuse of Drugs Act has been around for nearly 34 years. It was first developed at a time when our understanding of good drug policy was in its infancy and patterns of drug use were very different from today. It is now being reviewed, providing a rare opportunity for New Zealand to bring its drug law into the 21st century. In this essay, the Drug Foundation puts the case for reforming the Misuse of Drugs Act from a criminal justice-focused law to one that explicitly supports the health of people who use drugs and reduces drug harm across our communities.

The frontiers of human discovery advance at a remarkable pace. The way we see the world changes as events and knowledge alter our understanding of our environment and of each other.

The challenge for policy makers is to ensure that legislation keeps pace. Sometimes, important laws are allowed to fall out of step with public attitudes and scientific learning. That is the case with New Zealand’s now 34-year-old drug control law.

Our world is radically different from that of 1975, when a Bill Rowling-led government drafted the Misuse of Drugs Act. Back then, many New Zealandershad little or no exposure to drug use. Today, nearly half of New Zealanders under 65 acknowledge using cannabis at least once.

Some things have not changed. We know, as we did in 1975, that the misuse of drugs can hurt communities and individuals, but we have the benefit of 34 more years of scientific research, leading to a much better understanding of the best ways to reduce the harm drugs can cause. When it comes to policy and legislation, we know what works and what does not.

Since 1975, New Zealand politicians have made amendments to the Misuse of Drugs Act on several occasions. Unfortunately, many of these changes were driven by short-term political considerations. Today, we are left with a patchwork quilt of poorly considered amendments and outmoded assumptions.

In 2008, the Government asked the independent Law Commission to comprehensively review the Misuse of Drugs Act. This provides a long overdue opportunity to update the law, to ensure that it is ready for the future and supports the drug harm minimisation goals of our drug and health policies.

Ending the war on drugs

Experience has discredited the 1975 approach, which saw drugs purely as a matter for the criminal justice system and the deterrence and punishment of people who use drugs as the sole purpose of drug law. This is sometimes known as the ‘war on drugs’ approach, a term first used by President Richard Nixon in 1971 and usually linked with the harsh drug control tactics used in the United States that greatly inflated prison populations.

It is an approach that has proven ineffective both overseas and here. In isolated examples, strong law enforcement initiatives have contained the overall scope of a drug market, but researchers have struggled to find solid evidence for a straightforward link between efforts to clamp down on supply and a sustained drop in the availability or use of illegal drugs.

Fruitless attempts to prohibit alcohol last century demonstrated that trying to stamp out the supply of a product is a poor way of eliminating an entire market. Thai economist Pasuk Phongpaichit noted in a recent paper about her nation’s drug problem, “If you attack the supply but do little about demand, then the result is rising prices, rising profitability, and hence increased entrepreneurship.”

Entrepreneurship within the drug industry has thrived. Despite the fierce war on drugs waged by the United States and its allies over more than three decades, the global drug market has expanded exponentially.

Today, policy reform advocates believe that viewing the issue of drug use through the prism of health and social policy sharpens our understanding of the best ways to reduce the problems that drugs can cause. This means that we look at both drug demand and supply, which offers a wider range of up-to-date policy tools.

Social researchers also tell us that it is necessary to acknowledge the simple fact that people will continue to use legal and illegal drugs, no matter what legal approach is taken. While we will always want to reduce drug use, this fact means that we have an obligation to try to make drug use as safe as possible for people who use drugs and for the communities around them and that people can access essential health services.

In New Zealand, it is important for us to learn from the emergence of ecstasy, party pills and other designer drugs, and the phenomenon of diverted pharmaceuticals such as benzodiazepines and morphine sulphate. Our drug law has proved poorly prepared for such developments. New substances or variations of existing substances will continue to surface.

The outdated approach underpinning the Misuse of Drugs Act ensures that it has a heavily punitive focus on banning illicit drugs and attempting to control supply. The law is not adaptable. When new drugs emerge, they need to be fitted into a matrix of ‘harm’ and a political response planned.

The 34-year-old law divides drugs into classes, ostensibly on their risk of harm, and sets out the penalties for their possession, manufacture and supply. It gives power to the Police and Customs. In keeping with attitudes when it was first drafted, there is no emphasis on attempting to dampen demand, or on attempting to reduce the dangers to people who use drugs.

The inevitable result of this narrow approach is that far greater governmental resources go to control and enforcement than to programmes that focus on prevention or that deal with the harm that drugs cause.

It also means that artificial distinctions are made between legal drugs – notably alcohol and tobacco – and illegal drugs. In terms of economic impact and lives lost, tobacco is clearly New Zealand’s most harmful and costly drug, followed by alcohol.

As long ago as 1994, an advisory group told the Ministry of Health that “as a philosophical basis for drug policy, the justice perspective is very limited. Its underlying premise, that illegal drugs are ‘bad’ while legal drugs are generally ‘good’, is too black and white to be credible.”

Questioning the deterrence effect

The criminal justice approach relies on faith in the law’s power as a deterrent, as well as the idea that people choose to use drugs because they expect the rewards to be higher than the risks. In this context, criminal sanctions are intended to deter people from trying drugs or shifting to more harmful ones.

Looking at the world from this angle, we would expect the reduction of punishments (including through decriminalisation or legalisation) to cause the use of drugs to rise, and when a drug becomes illegal (as BZP did in 2008) or penalties are strengthened (as when methamphetamine was reclassified from Class B to Class A in 2003), use of that drug should fall.

In practice, things do not appear so clear cut. A 1999 report into United Kingdom drug laws by the Police Foundation found that “such evidence as we have assembled about the current situation and the changes that have taken place in the last 30 years all point to the conclusion that the deterrent effect of the law has been very limited.”

Deterrence critically relies on individual perception. Everybody has a different perception of risks and rewards, influenced by their social context, personal psychology and core values. This makes the provision of information a vital – and often neglected – element of deterrence-based public policy. People cannot be deterred from doing something if they do not understand the risks involved. For some people, the very fact that a drug is illegal will deter them from using it.

For similar reasons, people may choose not to jay-walk or to ride a bike without a helmet. However, legal status has clearly not proven a strong barrier to cannabis use in New Zealand, which is among the world’s highest.

According to sociologists and psychologists, legal sanctions may be less important than other factors in discouraging drug use. Their research tells us that social sanctions may prove more important, such as public exposure and shame if one is exposed as a person who uses illicit drugs. People are also affected by the fear of the effects of a drug, the fear of looking ‘uncool’ and the fear of embarrassing their family or community.

New Zealand research shows that non-cannabis users are much more likely to say they are simply “not interested” in the substance than to cite the risk of legal sanctions as their reason for abstaining.

Evidence shows that perception of health risks can be more important than legal sanction. The UK Police Foundation report concluded that “the public sees the health-related dangers of drugs as much more of a deterrent to use than their illegality.” The declining rate of smoking in New Zealand during the 1980s and 1990s highlights the potential benefits of a strong public information campaign about health risks associated with a drug.

Sending messages through drug classification

A flawed belief in the principle of deterrence underpins the Misuse of Drugs Act’s classification system, which was considered groundbreaking back in 1975.

In theory, the classification system is designed to associate greater legal risks with harder drugs that cause more damage for society and people who use drugs.

Of course, for a classification system to be effective, people using or selling the drug must be aware of the classification and its punishments. There is scarce research in New Zealand or elsewhere that proves that this is the case.

The classification of drugs is intended to be evidence-based. The Expert Advisory Committee on Drugs (EACD) makes recommendations to the Minister of Health based on factors including the likelihood of abuse, risk to public health, ability to create dependence and the classification decisions made by other countries.

In 2003, on EACD advice, the government reclassified methamphetamine from Class B to Class A. The Police Minister noted in November 2008 that, since then, the methamphetamine industry has grown. Despite a legal system designed to deter use, it would appear that industry participants perceive the rewards associated with methamphetamine creation and use as higher than the risks of legal sanction.

One apparent goal of pegging classifications to penalties is to deter somebody who tries a Class C drug like cannabis from moving ‘up’ to a Class A drug like methamphetamine.

Although most New Zealanders who have tried cannabis have not gone on to harder drugs, there is a widespread notion that Class C drugs – cannabis in particular – can serve as a ‘gateway’ to other drugs.

Indeed, this belief is consistent with American research that shows the use of cannabis is roughly associated with a stronger likelihood to try cocaine or psychedelics later. On the other hand, there is no evidence that the use of, say, ecstasy (a Class B drug in New Zealand) is followed by greater likelihood of using heroin (Class A). Research published in the Journal of Policy Analysis and Management concludes that the gateway concept remains controversial because a causal link between trying cannabis and trying harder drugs has not actually been established. This supports New Zealand research showing such ‘pathways’ exist, but that the ways they work are unclear.

The classification approach has been adopted in many countries. In the United States, drugs are divided into five schedules, but different states have their own legislation for scheduling drugs and for punishments. This means that one drug like ecstasy has different classifications and different punishments in different legal environments, which must undermine the deterrent effect.

In the United Kingdom in 2006, the House of Commons Science and Technology Committee took a close look at that country’s drug classification system and the workings of its equivalent to the EACD. The United Kingdom system is very similar to that of New Zealand: it has a three-tier drug ranking system of Class A, B and C.

The committee was troubled by the lack of research anywhere into such a system’s effectiveness. It cited evidence from the Chair of the Association of Chief Police Officers Drugs Committee that, “I cannot envisage any user – a dependent drug user, that is – having any kind of thought as to whether it was a Class A, B or C drug they were consuming.”

At the very least, this points to an information problem: if people who use drugs are not informed of the legal risks associated with different drugs, the deterrence effect will be fuzzy.

There is even anecdotal evidence that some people might see a Class A classification as an incentive to try a particular drug.

The committee was not sold on the argument that a classification system sends out ‘signals’ to drug users or potential drug users. Based on reported ballooning drug use in the United Kingdom, the committee felt that using the criminal justice system to send out public health messages about drugs was, at best, inefficient.

In the United Kingdom, the process by which drug classification decisions are made is often undisclosed and can be ill-defined, opaque and seemingly arbitrary. While New Zealand’s EACD goes to some lengths to promote transparency, the classification of drugs remains more of an art than a science.

In theory, three main factors determine the harm associated with any drug: the physical harm that the drug causes the individual user, the tendency of the drug to induce dependence and the effect of the drug’s use on families, communities and society.

In some cases, this is straightforward. Drugs that can be taken intravenously – such as heroin – carry a high risk of causing sudden death from respiratory depression and therefore score highly on any metric of harm. Methamphetamine also carries the risk of heart failure and seizures, and long-term chronic use can cause psychosis, aggression and violent behaviour. Cocaine induces very powerful dependence because higher doses are needed to obtain the same effect over time and because they create intense cravings and withdrawal reactions.

On the other hand, so does nicotine, which is a legal drug, and hallucinogens do not encourage physical dependence or carry a massive risk of causing sudden death, yet rate highly on both the United Kingdom and the New Zealand classifications. Because the longer-term effects of newer drugs like ecstasy are unknown, they can be difficult to classify.

Harm to society can be caused by many factors, including the damage to family and social life, as well as the costs to the health, social and justice systems. It is interesting to note that a legal drug – alcohol – creates a lot of accidental damage to users and to property through drunken behaviour and car crashes, while tobacco incurs higher costs on the healthcare system than any other drug.

In 2007, a research paper published in The Lancet used a group of independent drug addiction experts to attribute mean harm scores to illegal and legal drugs. One author of the paper was the chairman of the committee that recommends drug classification decisions to the British government.

“The results of this study do not provide justification for the sharp A, B or C divisions of the current classifications,” the researchers concluded. “Neither the rank ordering of drugs nor their segregation into groups… is supported by the more complete assessment of harm described here.”

From a scientific perspective, the researchers noted, the exclusion of alcohol and tobacco from the Misuse of Drugs Act was arbitrary.

The addiction professionals rated the drugs in the following order: heroin, cocaine, barbiturates, street methadone, alcohol, ketamine, benzodiazepines (e.g. Valium), amphetamine, tobacco, buprenorphine (e.g. the painkiller Temgesic), cannabis, solvents, 4-methylthioamphetamine, LSD, methylphenidate (e.g. Ritalin), anabolic steroids, GHB, MDMA (ecstasy), alkyl nitrates, khat.

The House of Commons Science and Technology Committee concluded there are startling differences between this ranking and that of the United Kingdom’s Misuse of Drugs Act. The same conclusion is reached when it is compared with New Zealand’s ranking.

One of the research paper authors told the select committee that the classification system “is antiquated and reflects the prejudice and misconceptions of an era in which drugs were placed in arbitrary categories with notable, often illogical consequences.” Even the Association of Chief Police Officers acknowledged that the classification system was “pretty crude”.

The committee recommended that the government decouple the harm ranking of drugs from the penalties for possession and trafficking. This would allow a more sophisticated and scientific approach to assessing harm and the development of a scale that would be responsive to new research.

The committee pointed out that a more scientifically based scale of harm would have greater credibility than a system where the placing of drugs in a particular category is ultimately a political choice.

Relying on politicians to make decisions about drug classifications can lead to science being overruled by short-term concerns such as media attention. The British system’s credibility was undermined between 2000 and 2007 when five successive Home Secretaries all sought to readdress the classification of cannabis amid a heated public debate. Eventually, the UK government ignored its scientific advisors’ recommendations and re-classified the drug.

Under our similar system, the same thing could occur in New Zealand. While we have not been engaged in a heated and politicised debate on cannabis recently, this is perhaps largely because successive governments have agreed in coalition deals not to revisit its legal status. This, in itself, has largely cut off the potential for evidence-based scientific input to public discourse.

Another advantage of decoupling the scientific harm metric from penalties would be that tobacco and alcohol could be included in a scientific scale to provide the public with a better sense of the relative harms involved with different drugs, legal or otherwise.

Reducing drug harm and promoting health

Promoting such health messages is part of the ‘harm minimisation’ approach. This pragmatic approach accepts that drug use will continue to be a part of society and that eradicating drugs by trying to stamp out supply is not feasible. Instead, the focus is on identifying the specific ways that drug misuse can harm individuals and society and then responding with strategies to reduce those dangers.

New Zealand’s National Drug Policy is based on this concept. The National Drug Policy is a regularly updated framework that was developed by the government in the 1990s to encourage action plans and community programmes to reduce the problems that drugs cause.

The National Drug Policy’s stated aim is “to prevent or delay the uptake of drugs, reduce drug-related harm, make families and communities safer and reduce the cost of drug abuse to individuals, society and government.”

Unfortunately, this dynamic up-to-date policy framework exists around a piece of legislation – the Misuse of Drugs Act – that has become dusty and irrelevant, with its limited goal of reducing supply.

The competing philosophies of the drug policy framework and the legislation create tension and confusion. The law’s strict focus on eradication of supply undermines health measures that would accept continued drug use. These could involve providing basic information on avoiding drug-related harm, or setting up needle exchange schemes and other harm reduction services.

The answer is not to throw out the criminal justice approach altogether. Nobody engaged in serious dialogue about the future of drug policy advocates creating an unregulated drug market in which traffickers and sellers go unpunished. However, it is important to broaden the legislation’s ambit. Genuine, effective attempts to reduce supply should be viewed as one tool that can be used to reduce the cost of drugs to society.

Drug use is different from drug production and supply. Too often, we lump everything together. Drug use is primarily a health issue and should be addressed through health-based responses. Drug production and trafficking, on the other hand, should usually remain the domain of a drug control system.

After years of viewing drug use through a criminal justice lens, it can seem jarring to consider the ‘rights’ of people who use drugs. However, international agreements like the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the World Health Organization’s Constitution make it clear that everybody has a fundamental right to decent standards of health. In the midst of a ‘war on drugs’ approach, this right is often denied to people who use drugs.

As Hungarian civil libertarian and researcher Judit Fridli points out, “Drug users are vulnerable people. They suffer from inadequate medical assistance. They experience discrimination, invasion of privacy, Police harassment and social marginalisation. They have to endure the arbitrary deprivation of rights.”

In many ways, incarcerating non-violent minor drug offenders has added to the damage harmful drug use causes, both to people who use drugs and to their families and communities.

Incarcerating users instead of providing appropriate healthcare might temporarily shut away the problem from society, but it means that we do not identify the underlying factors that cause somebody to use drugs in the first place or come up with a suitable long-term solution to an individual’s drug use. Overlooking drug users’ rights ends up costing society.

Research into different health-based responses to drug use has identified a number of initiatives that work effectively. Well-designed prevention programmes can support children to make healthy choices. Comprehensive harm reduction services can reduce the health, social and economic damage associated with using illegal substances.

These programmes work best in an environment of support and openness that is very difficult to foster when drugs are seen purely as a criminal justice issue. The fear of legal sanctions strongly deters people who use drugs from seeking help and stigmatises them. That means we miss out on opportunities to help people to give up drugs or to switch to safer forms of drug use.

New Zealand is not alone in trying to update the way it deals with drugs. Policy reformers have suggested changes in the United Kingdom, Australia and Canada in an effort to introduce a harm minimisation approach to drug control law.

In Canada, the Health Officers’ Council of British Columbia believes “The balance point for determining public health policies for currently illegal drugs would be that which minimises the prevalence of harmful use and negative health impacts, and also minimises any indirect o

r collateral harms to society from regulatory sanctions.”

And in the United Kingdom, Tom Wood, Scotland’s ‘Drug Tsar’, told a newspaper in 2006, “I spent much of my Police career fighting the drugs war and there was no one keener than me to fight it. But latterly I have become more and more convinced that it was never a war we could win. We can never as a nation be drug-free. No nation can, so we must accept that. So the message has to be more sophisticated than ‘just say no’ because that simple message doesn’t work.”

There is an obvious analogy with efforts to reduce the incidence of sexually transmitted infections. Research has shown that campaigns to promote chastity are usually ineffective, so a better approach is for campaigns to focus on encouraging safer behaviour.

Drug law focused on reducing the harm around drugs would help those communities that are particularly vulnerable to drug misuse, rather than exacerbating social exclusion by relying on incarceration to deal with people who use drugs. Law that is based on public health analysis would aim to reduce inequality. It would also recognise that, to reduce or stop drug misuse, recovery must be supported by the provision of social services, such as housing and employment.

A new Misuse of Drugs Act based on the principle of harm minimisation would make its top priority efforts to reduce the damage caused by drug use. It would recognise that many of the harms we currently experience from drugs are related to their legal status.

A health-based law would respect human rights, including the right of people to equal access to health services. It would reduce the barriers that currently stop people from seeking help for drug-related problems and make it easier for them to access services such as needle exchanges and other harm reduction programmes, treatment or emergency care for overdoses.

Such laws would complement other national public health laws and strategies, including the National Drug Policy framework.

Sociologists and researchers have provided us with a wealth of information about what would work better than our current law. The next step is to put these lessons to good use.

We have spent 30 years trying ineffectively to stamp out supply under the mistaken belief that drugs should be dealt with solely as a criminal justice matter. It is time to take heed of more than three decades of experience. Our drug law must be adaptable for the future instead of rooted in the past and, most importantly, supportive of drug and health policies.

References

New Zealand Drug Foundation. (October 2008) Taking a Public Health Approach to the Misuse of Drugs Act Review. Position Paper. Unpublished.

Pacula, R.L. (March 2008) What Research Tells Us About the Reasonableness of the Current Priorities of National Drug Control: Testimony presented before the House Oversight and Government Reform Committee, Subcommittee on Domestic Policy. RAND Corporation.

Phongpaichit, P. (October 2003) Drug Policy in Thailand. Speech to Senlis Council International Symposium on Global Drug Policy. Lisbon, Portugal.

Howden-Chapman, P., Bushnell, J., Carter, H. (1994) Prescription and Permission: An Analysis of Possible Philosophical Bases for Drug and Alcohol Policy in New Zealand. Paper prepared for the Ministry of Health.

Police Foundation. (1999) Drugs and the Law. Report of the Independent Inquiry into the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971. Chairman: Viscountess Runciman DBE.

Wilkins, C., Casswell, S., Bhatta, K., Pledger, M. (May 2002) Drug Use in New Zealand: National Surveys Comparison 1998 & 2001. Alcohol & Public Health Research Unit.

Tougher rules to combat 'P'. (26 november 2008) The New Zealand Herald.

Room, R. Social Policy and Psychoactive Substances. Chapter in Social Policy and Psychoactive Substances.

MacCoun, R., Reuter, P., Schelling, T. (1996) Assessing Alternative Drug Control Regimes. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, Vol. 15, No. 3, pp. 330-352.

House of Commons Science and Technology Committee. (July 2006) Drug classification: making a hash of it? Fifth Report of Session 2005-06.

Nutt D., King, L.A., Saulsbury, W., Blakemore, C. (2007) Development of a Rational Scale to Assess the Harm of Drugs of Potential Misuse. Lancet. Volume 369, pp. 1047-53.

Ministry of Health (2007) National Drug Policy 2007-2012.

Fridli, J. (2003) Harm Reduction and Human Rights. Harm Reduction News.

Wodak A., Moore, T. (2002) Modernising Australia’s Drug Policy. University of New South Wales Press.

Health Officers Council of British Columbia. (2007) Regulation of Psychoactive Substances in Canada: Seeking a Coherent Public Health Approach.

Recent news

Beyond the bottle: Paddy, Guyon, and Lotta on life after alcohol

Well-known NZers share what it's like to live without alcohol in a culture that celebrates it at every turn

Funding boost and significant shift needed for health-based approach to drugs

A new paper sets out the Drug Foundation's vision for a health-based approach to drug harm

Expert Pharmac committee recommends funding for overdose reversal nasal spray

The expert committee has said funding for naloxone in the community should be a high priority