Underdosing naloxone

Globally, an estimated 69,000 people die each year from opioid overdose. The drug naloxone can quickly block opioid receptors in the brain and is used in some cases to bring people back from the brink of overdose death. Amberleigh Jack looks at why naloxone is not being used more widely.

Mark Kinzly almost died from opioid overdose. Twice. He survived thanks to a life-saving drug known as naloxone. Others he knew weren’t so lucky. “I’ve watched my community die,” he tells me. “The community is dying – either from AIDs or drug overdose – and the community has been dying for decades.”

These days, he’s off the drugs, lives in Texas and is an overdose prevention advocate. Unsurprisingly, he thinks the medication that saved his life should be an over-the-counter drug.

Naloxone works by instantly blocking opioids from receptors in the body, stopping them having any effect. It works in minutes and has the ability to bring people back from the brink of death. Its availability is a major part of overdose prevention programmes, particularly in the US.

The recent attempts by government to prevent overdoses is a good start, according to Kinzly, but there’s still much more than can be done. And largely, it comes down to that vital drug.

“I have a 16-year-old son,” he tells me, referring back to his own near-fatal experiences.

“I bet if you talked to him he’d be pretty happy that naloxone was available.”

But for too many others, the potential lifesaver has not been at hand. Now, overdose prevention advocates, often with the backing of government officials around the world, are increasing efforts to actively prevent overdoses and make naloxone more readily available, saying hundreds of lives are being unnecessarily lost. As yet, nothing is happening in New Zealand, and perhaps it’s time to ask why.

In the US in October 2014, the Office of National Drug Control Policy’s Acting Director Michael Botticelli (otherwise known as the White House Drug Czar – the first person to hold the title who is in recovery himself) told the Harm Reduction Conference in Baltimore a disturbing fact. In 2010, there were 38,000 overdose deaths in the US – a figure that superseded the road toll deaths in the same year (35,000). The number of road deaths has been steadily declining for the past two decades, while the drug overdose death rate has more than tripled.

In 2012, 41,502 drug overdose deaths were recorded in the US – almost 80 percent of which were accidental, and almost 7 percent were of unknown intent. And the drugs? More than half were pharmaceuticals, and more than 70 percent of these were opioid analgesics. The non-pharmaceutical deaths? Heroin, mostly, either on its own or combined with alcohol, pharmaceuticals or cocaine. Looking further into the stats makes for some depressing reading. In 2011, there were about 2.5 million visits to US emergency departments due to drug misuse and abuse. Around 71,000 of those were by people under 18 years of age.

And it’s not just the US. Globally, an estimated 69,000 people die each year from opioid overdose (both pharmaceutical drugs like Oxycontin and morphine as well as illegal drugs like heroin and ‘homebake’ opioids). In the US, it’s hit epidemic status, and the rest of the world is seeing increases, especially as prescription medicine misuse is on the rise. It’s also no longer limited to the streets. With the rise in prescription opioids, middle-aged women are one of the rising demographics for overdose rates.

Recent statistics suggest that more than 400 people died of a drug overdose in the four years between 2009 and 2013.

And the world is starting to take notice as it struggles to get the rates under control. While the ultimate goal is to reduce use and abuse, as Allan Clear of the Drug Harm Coalition in New York says, “You can only help people get off drugs if they’re alive.”

Enter naloxone. It’s a major component of overdose prevention programmes and methods. A lifesaving drug that, if injected quickly enough, reverses opioid overdose and does so safely. It’s been around for decades, yet in a number of states, it’s been difficult to obtain until recently. It was in 2001 that the Chicago Recovery Alliance first established a US programme to allow injectible naloxone to be prescribed. By 2010, this decision had resulted in more than 15,000 naloxone prescriptions being filled to potential overdose witnesses, with more than 1,500 reported overdose reversals. In 2011, 15 states had introduced more than 180 programmes that had doctors available to prescribe naloxone. By this time, more than 10,000 overdoses had been recorded and more than 53,000 people trained in naloxone administration.

In New Zealand, users can obtain naloxone in an emergency situation when paramedics are called or by being presented to a hospital emergency department while overdosing (as long as the hospital carries naloxone – most do, but a few don’t).

When asked why the drug is so difficult to obtain in New Zealand, Susanna Galea – a consultant psychiatrist and Clinical Director for the Alcohol and Drug Service within the Waitemata District Health Board – says she doesn’t believe we have a need for it. She’s worked previously in the UK. Compared to there, she tells me, our issue is minor.

“We don’t have a massive overdose problem. Yes, people are dying,” she admits, “but it’s not a big problem. I’d say in terms of people dying, it’s more around medical complications from overuse (such as cardiac arrest due to excessive methamphetamine). That’s not to say we don’t do any overdose prevention at all. It’s integrated within the harm reduction philosophy and within the patient’s care plan. So, no, there’s no need to start dishing out naloxone. Note 1

Yes, comparatively, the figures are small in New Zealand. They’re also incredibly difficult to find. Recent statistics suggest that more than 400 people died of a drug overdose in the four years between 2009 and 2013. Of these, it’s estimated that an average of about 30 people per year die of opioid overdose. Sure, it’s nothing compared to the figures in the US, but compared to our road toll figures, it’s a decent chunk. To borrow a term commonly used by the Police concerning road fatalities, “One death is one death too many.”

There’s also another factor to consider. Oxycontin has been available since the 90s in the US, whereas it was introduced in New Zealand in 2005. In that time, prescription numbers have increased by more than 700,000. And we have 10 years of catching up to do.

But Kinzly says the best way to deal with the problem is to catch it before it becomes a massive problem. “Why would you wait until you’re in a situation like the US?

“It’s always nice when you get the opportunity to deal with something that could potentially become an issue and put something in place early enough so that it doesn’t. It just makes sense, it’s really good public health,” he says emphatically.

“It’s going to happen. Why would New Zealand be any different? Why would you wait until you’re in a situation like the US is where it’s an epidemic? One of the great things about New Zealand, you guys have been really progressive around areas of public health. Why would this be any different?”

So what exactly does New Zealand do by way of overdose prevention? It’s hard to say. The needle exchange centres (there are 21 across New Zealand) include information and education on overdose prevention for clients. It seems that for most, though, it’s not a huge priority. This is probably due to the theory that heroin, in the last couple of decades, hasn’t been a major issue in New Zealand. We have users, but they’re relatively confined and pretty rare. Heroin’s hard to get here and expensive. Charles Henderson, the head of the Needle Exchange Programme, is quick to point out, though, that when the figures are looked at on a per capita basis, injection drug use is very much alive in New Zealand. For many, it’s a case of “out of sight, out of mind”.---

Peter Kennerley of the Ministry of Health’s Addiction Treatment Services admits New Zealand has a problem with drugs but says the problem is more alcohol and amphetamine related. Our people are dying, but they tend to die of medical complications brought on by other drugs rather than overdose, he says. Government funding tends to be focused on harm reduction and education around drug and alcohol abuse.

Kennerley explains that New Zealand has a multifaceted approach to harm reduction, and the idea of overdose prevention is integrated within that, focused mostly on education and stricter prescription monitoring.

“It’s a part of the overall service,” he says.

“There’s no one approach, but it’s partly around giving consumers choices and different sources of information. My concern would be when opioids are prescribed for pain management. People may end up with an addiction and start using them inappropriately. It’s something that needs to be looked at.”

He’s right, too. In New Zealand, deaths are occurring. Similarly with the US, the headlines are happening in the provinces. And it’s been happening for a few years. Vito Vari was 40 when he was found dead in his Nelson home in August 2011. The New Zealand Herald reported the coroner finding to be death by accidental overdose. The drug? Oxycontin.

---

It was the surging rates of accidental overdose death in the US that led to recent law changes, of which there are two main arms. The first is wider access to naloxone, the second is an increase in states that have passed Good Samaritan laws, providing immunity for people who seek help when someone has overdosed without fear of civil liability or prosecution.

In New Zealand, paramedic and hospital staff don’t tend to call the Police unless necessary, but Henderson suggests that the Police often tend to turn up in an overdose situation.

“We recommend that the first point of call is to dial 111,” he tells me.

“One problem we’ve got is that, if drugs are mentioned, it can be likely that the Police will arrive. There’s plenty of anecdotal evidence that the Police then do think about arrests.”

The Needle Exchange’s advice to rectify this isn’t without its flaws, though.

“We’re in a bit of a no-win situation, because our advice to clients would be that they should possibly avoid the naming of the drug used, because that immediately can result in charges. But it’s my understanding that St John’s only carry naloxone with advanced paramedics.”

So the risk is that, by avoiding arrest, a paramedic may arrive who simply doesn’t have the lifesaving drug on hand. Following suit with US immunity laws, Henderson suggests, would help a lot.

One of the great things about New Zealand, you guys have been really progressive around areas of public health.

Mark Kinzly

In the US at the end of 2014, 20 states had introduced Good Samaritan laws providing immunity from prosecution or civil action if someone used a prescription that wasn’t theirs or was found to be intoxicated or to have gear on them at the overdose scene.

Since then, availability has increased further. Now, 22 states have increased naloxone availability for users and bystanders, and while traditionally only a doctor can prescribe directly, states such as New York and California have loosened the rules to allow doctors to prescribe for harm reduction and syringe exchange programmes without having to be present to distribute the prescriptions. As well as this, with the backing of the Federal Government, the Police forces and armed defence forces have been trained and supplied with naloxone over the past year.

The big rise in the use of prescription opioids, and the resulting increase in addiction and overdose, have brought the problem to the forefront of the public mind, says Allan Clear, and so have the high-profile deaths of celebrities including actor Philip Seymour Hoffman.

“The focus on opioids is a strategy we adopted a few years ago,” he tells me about the Harm Reduction Coalition’s approach to education and overdose prevention.

“There’s a ban on using any federal money to supply syringes to anyone else. So our focus [for funding and support] became much more on opioid overdose [and pushing for access to naloxone and education tools]. Even when you talk to Democrats around syringe exchange, if they come from places like Minnesota, they basically say, ‘This is a big city problem. It’s not our problem. We don’t have it’.”

It’s a different story with prescription medication though.

“But when you talk about prescription drug use – people [in government] from places like Minnesota or Wisconsin – they all get it. And very often they say things like, ‘My brother-in-law had a problem,’ or ‘My cousin has been in rehab’.”

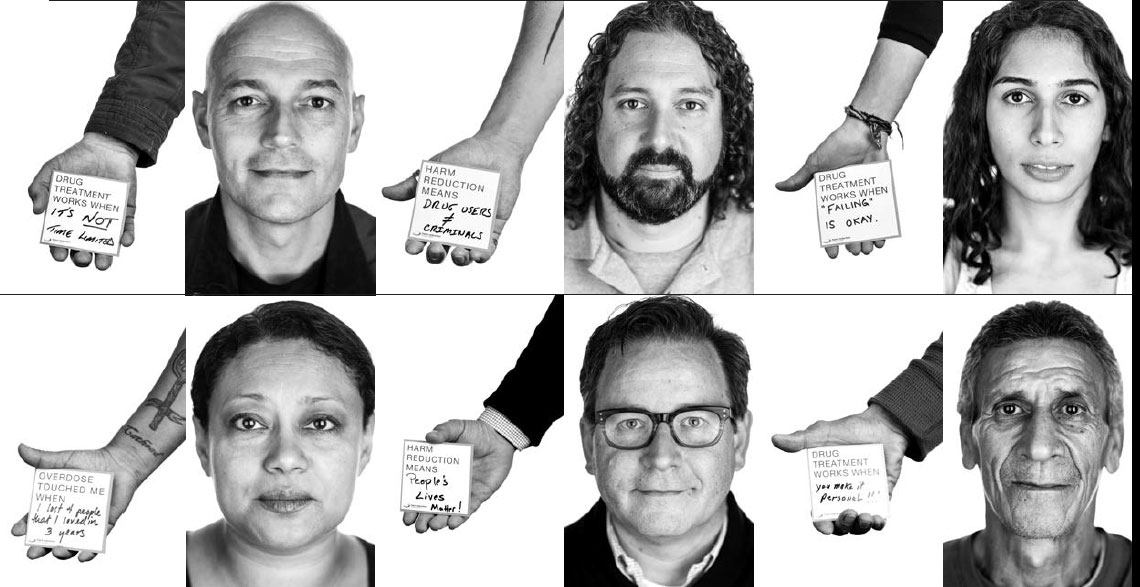

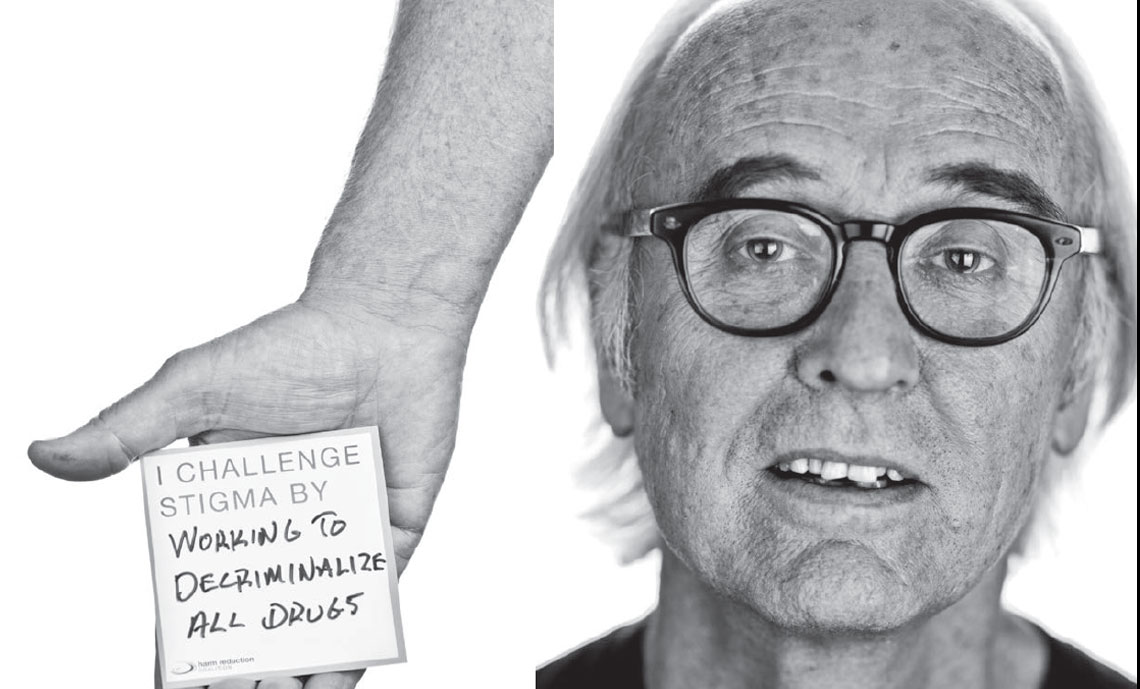

That stigma and discrimination around drug use is an issue in Australia as well – one that isn’t necessarily stopping strong overdose prevention measures but one that can definitely make them more difficult to implement without support from the top down.

In Australia, Tony Trimingham knows more than he’d ever want to about drug overdose – and the stigma around use and abuse. In 1997, his son Damien, aged 23, was found dead in a disused hospital corridor in Sydney after overdosing on heroin. He was a regular user but had recently had a period of abstinence. The lowered opioid tolerance contributed to his fatal mistake. Shortly after, Trimingham found himself struggling to find support and information and ultimately created Family Drug Support – a non-profit organisation that helps families find support, information and help when it comes to loved ones’ drug use. When he talks about his son and the stigma around his untimely death, Trimingham has the same tone of voice I’m now all too familiar with. The quiet conviction – something that conveys both deep pain and regret as well as a fierce determination – especially when it comes to that all-too-common stigma.

“It’s still as strong as ever,” he insists.

“I’ve known lots of families that lost people and have never stated the fact it was a drug overdose. There’s a lot of pressure on families not to talk about it.

“I don’t think it applies in any other area. People with mental illness are now speaking out, and the stigma is reducing as they do that. But not for drugs. It’s still the leprosy of the modern age. It affects the drug users more than anybody, but next to that, it’s the families.”

It’s an attitude that’s not just confined to Australia.

Back in Texas, Kinzly believes that stigma is one of the biggest hurdles to making appropriate services available – whether that’s harm reduction, overdose prevention or even housing. And it can make overdose more likely simply because of the shame attached to using.

“That stigma means we don’t tell people we’re using,” he says.

“We need to encourage people to be more open. Find someone you trust, even if they’re not with you. Most of us don’t die immediately. It takes about one to three hours. If I call you up and say, ‘I’m getting ready to use, check on me in an hour or so’ – do you know how many lives we could save just by teaching people not to use alone or to have somebody check on them?”

It’s something I understand. My own brother Barnaby died of a heroin and cocaine drug overdose in his San Francisco apartment. While intervention measures such as naloxone would likely have been able to save him (the drug doesn’t affect the non-opioid cocaine in the system, but often with combination overdoses, removing the opioids is enough), there wasn’t an opportunity as he was alone. He wasn’t found until it was too late. He also hadn’t told anybody he was using. He was highly intelligent, a world-class computer security expert who travelled the world speaking at conferences and to government officials. Friends have suggested he never told us of any drug use because he feared we’d be disappointed. By the time we found out, it was too late. And even then, the word ‘overdose’ is just beginning to be spoken within our family. My mother is only now willing to let people know how he died. The stigma is real, and everyone seems to agree it needs to change for any real overdose prevention intervention.

In some ways, though, attitudes are changing. And the reasons seem to be related to the rise in prescription opioid pain medications.

“What’s happening in regards to overdose is that, because of prescription drugs and how it’s affecting suburban areas, white middle and upper class kids are being affected,” says Kinzly.

“So the affluent, influential mothers and fathers, sisters and brothers are now making noise. It’s like, well now our kids are dying, so we have to do something.”

Allan Clear has found a similar shift in attitude with the Police he’s worked with through naloxone distribution and training.

In the US, 21 states currently have trained Police departments carrying naloxone. New York has more than 150 departments involved in the programme. Already in January, one department – Buffalo PD – recorded three overdose reversals. In Massachusetts, known to have a major heroin problem, one department – Quincy PD – had recorded 300 overdose reversals as of September 2014. Most departments list at least one recorded save or reversal since beginning the programme.

It takes about one to three hours. If I call you up and say, ‘I’m getting ready to use, check on me in an hour or so’ …

Mark Kinzly

Perhaps that’s what has helped make the work with the police and other frontline staff more open to being involved. It’s no longer just a problem for typically homeless black addicts, suggests Clear, but for neighbours and friends of the fairly affluent working class. He highlights this with his recent experience training Police officers in the administering of naloxone.

“I was taken aback to watch a cop do the trainings with other cops,” he says.

“I’ve done Police trainings [in the past], and they’re usually incredibly hostile. I recall back in the 90s, I once said, ‘You can’t get HIV from heroin,’ and one of the cops said, ‘Well that’s a shame isn’t it’.”

But now?

“It was astonishing [recently] to hear [a Police trainer] talk about how it’s the duty of the Police to revive someone from an overdose. Back when we started, the Police notion was that we’re better off without them. When you see Police reversing overdoses and taking an active role in preserving the lives of drug users [by organising treatment rather than making arrests], it’s astonishing they’re taking that on, because a few years ago, they wouldn’t have seen it as part of their job.”

The reason? Clear thinks the rise in prescription overdoses is a big part of it.

“A place like Staten Island is considered predominantly white, blue collar working class – it’s a Republican part of New York – and it’s been hard hit by overdose. Cops and firemen are seeing the problem in their own communities. People they know are dying of overdose. That may affect the attitudes.”

Not that the stigma doesn’t exist though or that there aren’t problems with introducing prevention programmes that people get on board with.

“I guess it’s all relative. It’s still highly stigmatised. We do amazing work in New York, for example, but then you go down south, and it’s incomprehensible to me. It seems the efforts of local government down south deprive people of healthcare. You won’t find sympathy for drug users in virtually any of the southern states. You have great disparities in services and enormous disparities in health outcomes.”

Closer to home, Australian heroin use has been a growing issue for decades, with 1,100 heroin overdose deaths being reported during the country’s “heroin glut” in 1999. While heroin deaths have decreased since then, opioid overdoses are on the rise. Naloxone is available through syringe exchange centres and programmes such as Victoria’s COPE (Community Overdose Prevention Education). While the drug is available, there are still major restrictions. Naloxone in Australia can only be prescribed to the user, not to a potential witness. This, of course, relies on users specifically seeking out a doctor and rules out concerned family or friends from being prepared with the antidote. As with the US, overdose rates were higher than road toll deaths in 2013, with road accidents in Australia resulting in 242 deaths compared with 374 overdose deaths (including intentional). 310 of these involved prescription medications.

Belinda McNair of the Penington Institute – which works on improving overdose prevention across Victoria – says she struggles to understand why naloxone isn’t widely available.

“I’ve been trying to find ways where the drug could be misused in some way,” she tells me.

“If you give it to someone who isn’t suffering an opioid overdose – nothing happens. If, God forbid, a child finds it and injects its brother – the brother will cry because he just got a needle in his arm – that’s it.”

One thing everyone agrees on is that a major aspect of overdose prevention is education. The US, again, has multiple community groups and programmes designed to educate users and families on how to prevent overdose, ranging from simply not using to full video tutorials online about how to administer naloxone.

Back here, Galea says that education is a large part of overdose prevention in New Zealand – that it’s incorporated into programmes, particularly in regard to lowered tolerance due to abstinence following hospital or rehab stays.

“We do have an inpatient unit. Once they’ve been detoxified, if they go back to their pre-treatment dose, there is a risk of overdose. We do teach them that, and we teach them about tolerance. We also have what we call post-detox groups for vulnerable periods.”

So what needs to happen? Some say a lot. Henderson is a firm supporter of naloxone being made available in New Zealand, And he’s quick to point out, if the estimated figure of 30 deaths per year is correct, that’s not an insignificant number. His hope? That the drug will be rolled out, and that the easiest way to implement it would be through the Needle Exchange Programme.

“Through needle exchanges, we certainly hear enough anecdotes of overdoses occurring ... We need to be able to have the training measures in place to roll out something like naloxone.”

Kinzly believes at some point naloxone will be available as an over-the-counter drug. But there’s a way to go yet.

“It’s rare that we have the opportunity in our lifetime, with an epidemic going on, to dramatically curb it just by making a couple of simple things accessible. We can make a dramatic decrease in overdoses just by making the medication available. For whatever reason, we don’t do that.

“How do you give somebody something that’s potentially fatal and not give them a medication that could potentially save them from that fatality? It’s just unethical.”

Similarly, Australia needs improvement, according to Trimingham, and it’s something that needs to start from the top.

“I’d like to see a more willing attitude from the people that have the power to exact legislation. People don’t want to go anywhere near anything that might have anything to do with drugs or be seen to be condoning use,” he says.

“It’s not though,” he continues. “It’s accepting reality.”

And for New Zealand? Kinzly has a word of advice. Our overdose rates may not be large, but they’re important enough to warrant intervention. And prevention starts with making naloxone more freely available.

He refers back to my own situation and to his near fatal overdoses.

“That’s it right there,” he says.

“Whether it’s 30 deaths or one death, it doesn’t matter. To that one person’s family, it’s a big fucking deal.”

Amberleigh Jack is a writer based in Auckland.

Note 1 After publication of this story Dr Susanna Galea requested the Drug Foundation insert a clarification about her position.

Clarification requested by Dr Susanna Galea

The following clarification refers to the ’Underdosing naloxone’ article that appeared in the February issue of Matters of Substance. It is included at the request of Dr Susanna Galea, Clinical Director Community Alcohol and Drug Services, Waitemata DHB:

“I was concerned to read the comments attributed to me in the ’Underdosing naloxone’ article. The statement “she doesn’t believe we have a need for it” does not accurately reflect my opinion, and I would like to provide clarification.

Compared to other countries (for example, the USA and UK), New Zealand does not have as ’big’ an overdose problem. The majority of drug-related deaths tend to result from associated physical health comorbidities – such as death from liver cirrhosis, due to comorbid hepatitis C infection.

The reasons for this, in my opinion, are most likely related to the fact that heroin is not the most commonly used/abused opioid in New Zealand, that treatment approaches have a focus on ’family inclusive practice’ and that there is strong consumer representation and choice. I believe that these approaches have an impact on enhancing safer practices and harm reduction.

My view is that naloxone should be given to clients who are considered at risk of overdosing, not to all clients presenting to treatment services. In agreement with the client, in some cases, it may be more helpful to give the naloxone to ‘significant others’ (could be family, whānau, friends) because the client who overdoses would not necessarily be in a position to take the medication, but the ’significant other’ could play an important role in providing it to the client at a crucial time. Naloxone should be easy to access – e.g. from pharmacy outlets as is required.”

Recent news

Beyond the bottle: Paddy, Guyon, and Lotta on life after alcohol

Well-known NZers share what it's like to live without alcohol in a culture that celebrates it at every turn

Funding boost and significant shift needed for health-based approach to drugs

A new paper sets out the Drug Foundation's vision for a health-based approach to drug harm

Expert Pharmac committee recommends funding for overdose reversal nasal spray

The expert committee has said funding for naloxone in the community should be a high priority