Viewpoints: Should unregistered naltrexone implants be used to treat opioid dependence?

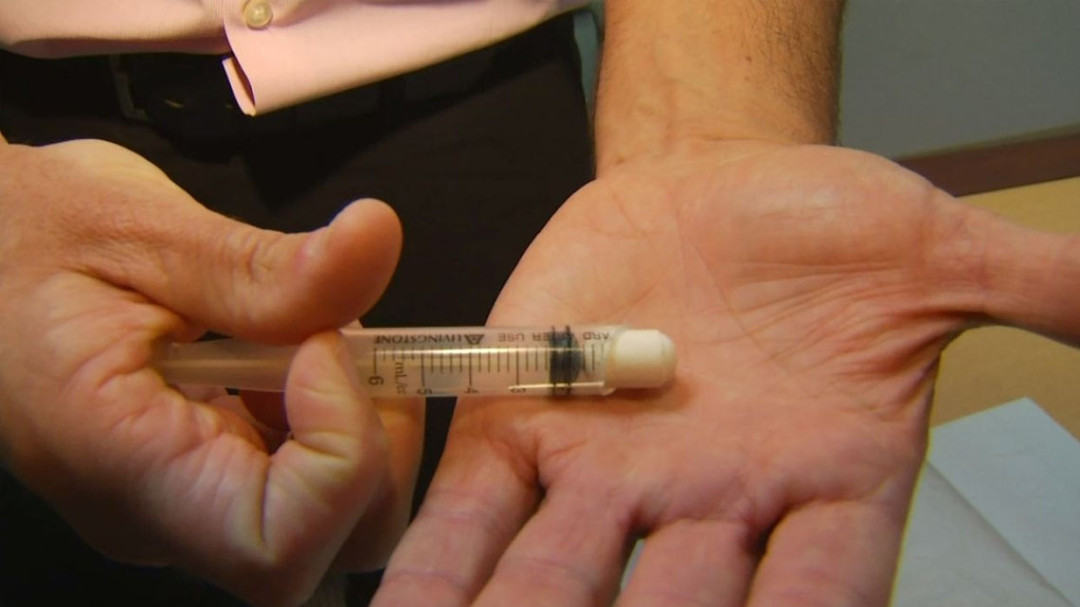

Thousands of Australians have been implanted with sustained-released naltrexone in an effort to help them overcome opiate addiction. Theoretically, it makes sense: block the body from experiencing the effects of opiates. But there are problems. Naltrexone is still being tested and is unregulated. It’s a controversial situation, but given the extreme circumstances so often faced by those with an opiate addiction, is the potential return worth the risk?

The case for

Heroin addiction is not something you’d wish upon your worst enemy. It tends to come with a lifestyle of chaos, carnage and criminal justice involvement. It also tends to come with health complications, including high rates of communicable disease and even death. The life of a heroin addict is not exactly safe. It’s also not an easy life to escape. So when a potential pathway out of that lifestyle is available, even if it’s risky, people should have the opportunity to take it. We’re talking about consenting adults here. Who are we to prevent sick people from taking something that could help them get better?

Plus, it’s not like the current options are perfect. Right now, the gold standard for treating opioid dependence is methadone. Although it is well evidenced, methadone is not without its problems. It is highly addictive, has a longer withdrawal period than other opiates, can be fatal and doesn’t prevent people using other drugs, including heroin, while undergoing methadone maintenance. For some, the benefits of methadone undoubtedly outweigh the potential risks. For others, however, methadone either hasn’t been or is unlikely to be successful. People deserve to have options.

Although naltrexone implants are less well evidenced than methadone, emerging evidence shows that naltrexone implants appear to compare favourably. Ngo et al. (2008) found mortality rates for patients with naltrexone implants were comparable to those of a methadone cohort. Furthermore, those with naltrexone implants presented to hospital less frequently for non-fatal opioid overdoses than those using methadone.

Although there is less evidence available on the efficacy of naltrexone implants than there is for other pharmacotherapies for opioid addiction, they definitely show promise. Given the limitations of existing therapies and their unsuitability for certain people, naltrexone implants should continue to be available to those who are willing to try them for themselves.

The case against

The reason that we have a process for regulating medicines and other therapeutic goods is that we only want people to be taking things that are proven to be safe and effective. At this stage, naltrexone implants simply do not fall into that category.

In terms of clinical data, there is not enough quality evidence available. The most systematic review conducted to date was carried out for Cochrane by Lobmaier in 2008. It failed to find any randomised controlled trials that assessed the efficacy of naltrexone implants for treating people with opioid dependence.

There have been a number of studies conducted on naltrexone implants since the Cochrane review, but there are still significant issues with the quality of available evidence. For the most part, studies use the same base cohort, data is derived from small samples, and studies with larger sample sizes tend to be based on retrospective analysis. To put it simply, the data is unreliable.

Better evidence is crucial given the reported adverse effects. These include wound opening and localised infection, allergic reactions, implant removal, headaches, nausea, vomiting and psychological issues. These also include death. Comparing a cohort taking methadone with one implanted with naltrexone, Ngo et al. (2008) found that the implant group was at greater short-term risk of non-opioid overdose. Furthermore, hospitalisations due to non-opioid drug use increased significantly. The authors note that changes were robust, long lasting and common across all genders and ages. Similar results were not found with methadone.

The Australian experience adds even more weight to the notion that these implants are risky – particularly in an unregulated environment. There have been a number of highly publicised deaths – most recently three patients at a clinic run by someone who wasn’t even a medical doctor. Yet given that these implants are not regulated, there are no protections offered if something goes wrong. There also seems to be scant oversight on those who are providing these implants at significant cost to people who are desperate to change their lives.

Yes, people who are trying to recover from heroin addiction deserve all the help they can get, but they also deserve to be protected from further harm as they strive to free themselves from their addiction. The current situation is simply not acceptable and could indeed be considered exploitative. While naltrexone implants definitely deserve further clinical trialling, they should not be available as a treatment option until they are proven to be safe and effective.

Recent news

Beyond the bottle: Paddy, Guyon, and Lotta on life after alcohol

Well-known NZers share what it's like to live without alcohol in a culture that celebrates it at every turn

Funding boost and significant shift needed for health-based approach to drugs

A new paper sets out the Drug Foundation's vision for a health-based approach to drug harm

Expert Pharmac committee recommends funding for overdose reversal nasal spray

The expert committee has said funding for naloxone in the community should be a high priority