Veronal: who remembers veronal?

The meth 'menace' with its savage violence, property contamination and million dollar seizures continues to tear at the country’s social fabric, testing health and law enforcement authorities. But actually, the current outcry over methamphetamine use and manufacture is just part of a long tradition of moral panic over dangerous drugs in Godzone, some of which may have faded into historic obscurity. Like, how many of us have heard of veronal?

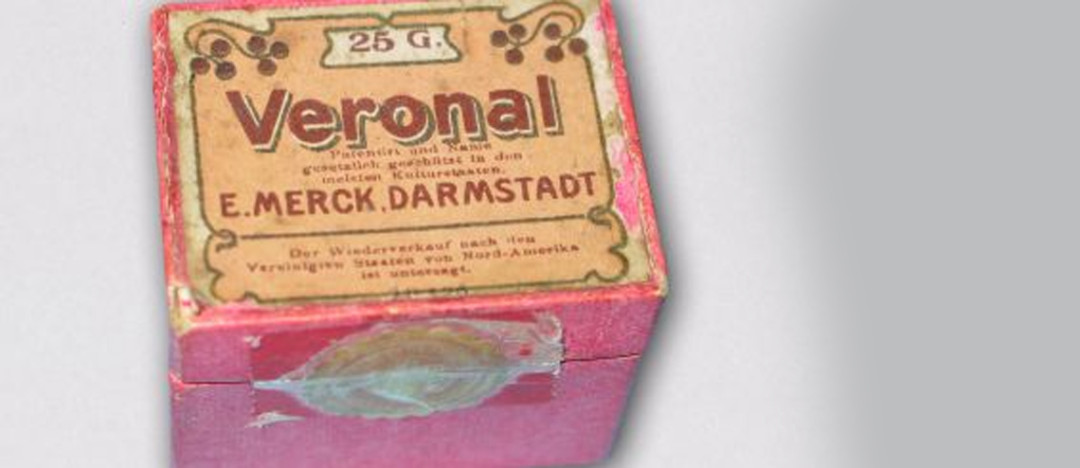

Our first drugs sensation dates back to the 1930s when a lethal sedative with the catchy name ‘veronal’ caught the popular imagination. Quite favoured by writers like Katherine Mansfield, this first commercially available barbiturate became linked to the glamorous London jazz scene of the 1920s.

New Zealand was not far behind. Veronal became notorious here in 1935, as the ‘sleeping potion’ used by flamboyant Auckland musician Eric Mareo to kill his wife after he found her in bed with another woman. Twice condemned to death for murder, he only narrowly avoided the noose.

So what is veronal and how widely used was it here? In 1903, doctors synthesised the first diethybarbituric acid, hailing it as an “infallible cure for insomnia”. Billed as safe and non- addictive, it was an immediate success in Europe. The overdoses and deaths then began.

At the time of World War One, veronal was probably best known to New Zealanders as the name of a prominent racehorse. Then a young woman named Annie Travin overdosed in Gisborne, the first known local case. Her hospitalisation came as a wealthy gay aristocrat named Hugh Eric Trevanion died in London of veronal poisoning. Scandal sheet NZ Truth wrote of Trevanion: “he was exceedingly effeminate and lisped like a girl ... he wore a kimono and white kid shoes with high heels in the house”.

The Press was quick to investigate the ‘veronal habit’ but found it was all hype. A reporter concluded “it appears that veronal is fairly costly .... as far as could be ascertained, there are no known cases in Christchurch...” Truth, meanwhile, reported that a Nelson woman had used it in a suicide attempt at an Auckland hotel after being spurned by her lover.

During the 1920s, local veronal use accelerated. Though a doctor’s prescription was officially required, an inquest into the death of an Auckland woman heard “the tablets could be bought from a chemist like a bag of lollies. Many people considered veronal tablets on a par with aspirins.” So many deaths were linked to the drug by 1930 that the New Zealand authorities added it to the prohibited poisons list, along with morphine and cocaine.

Writer Robin Hyde, a sometime user, noted in 1932 “that it had been the cause of so many recent tragedies that the New Zealand Pharmacy Board is moving in this direction. Every chemist in New Zealand has reason to know and fear the effects of veronal when it is rashly used, or administered by people who do not realise its deadly power. The Auckland district, in particular, has in the last few months acquired a veronal death-roll of which it cannot be proud.”

A Poisons Act was then drafted, ensuring veronal could only be obtained with a prescription. Weeks before the law came into force in 1935, Auckland was rocked by a sensational murder with veronal at its heart.

The case involved bandleader Eric Mareo and his actress wife Thelma, two ‘artists’ living a flamboyant lifestyle in Auckland’s Mt Eden, both veronal addicts. Mareo, a charismatic Australian, stood out from the scruffy Depression-era crowds, famously walking down Queen Street with “a cigarette holder in one hand, a cane and gloves in the other”.

Eric and Thelma, his fifth wife, were habitués of the Dixieland cabaret on the corner of Queen and Waverley Streets, with its sprung dance floor. Patrons enjoyed live jazz and illegal liquor. Truth talked of “an orgy of jazz and fizz” at the cabaret and of drunken flappers “whose knees gave way beneath them”. The sleepy Queen City was waking up: nightlife had hitherto consisted of musical theatre and silent movies.

Dancer Freda Stark, famous for painting herself gold, was a regular visitor to the Mareos’ home at Tenterden Avenue. It was there on 15 April 1935 that Mareo gave Thelma a fatal dose of veronal in a glass of milk. Both were said to be daily users of the hypnotic, who spent a lot of time “canned” or intoxicated. After the coroner diagnosed veronal poisoning, Mareo was charged with murder.

In the lengthy trial that followed, Stark was the main witness for the prosecution. As the word ‘lesbian’ echoed in the courtroom, Mareo testified that “his wife’s desires were met by association with women”. Stark’s testimony that Mareo was jealous helped secure his conviction.

Twice condemned to death, he eventually served 12 years in prison. The case attracted such public attention that when a jury found Mareo guilty, the news was flashed onto the screen in Auckland picture theatres. The audience cheered.

Robin Hyde speculated that economic insecurity was behind the increased use of drugs: “It has undoubtedly caused increased nervous strain, and has weakened the resistance of men and women who a few years ago would have shunned the drug habit”.

She was not far off the mark. Mareo was struggling financially. He’d recently lost his job as a bandleader and was facing economic ruin. He was also worried about the impact of the Poisons Act on his supplies and had gone chemist ‘shopping’ to stock up. As a result, Thelma, Freda and Eric had been bingeing for days.

During his trial, Mareo openly confessed to being a drug addict, but for a conservative 1930s jury, this counted against him. As a supporter later explained: “... the prejudice against him tightened considerably. You see to those honest citizens from whom juries are selected, there’s something heinous about the very word ‘drug’... the fact that Eric Mareo was a self-confessed addict enormously depreciated his chances of an acquittal.”

Mareo proclaimed his innocence until his death in 1958. Veronal meanwhile dropped from sight, replaced by equally lethal forms of barbiturate. These were widely prescribed (and abused) as sleeping pills or ‘downers’ until the mid 1970s. Today, barbiturates are only prescribed for serious insomnia.

Recent news

Beyond the bottle: Paddy, Guyon, and Lotta on life after alcohol

Well-known NZers share what it's like to live without alcohol in a culture that celebrates it at every turn

Funding boost and significant shift needed for health-based approach to drugs

A new paper sets out the Drug Foundation's vision for a health-based approach to drug harm

Expert Pharmac committee recommends funding for overdose reversal nasal spray

The expert committee has said funding for naloxone in the community should be a high priority