What we've learned from a crisis

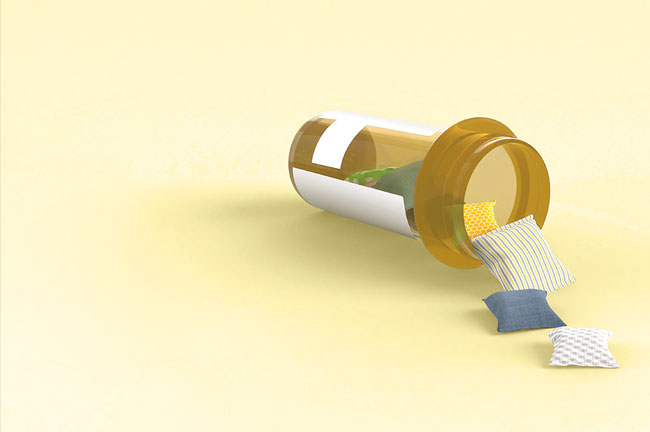

Lockdown and the continued impacts of the coronavirus have already changed the way the addiction sector operates. As we head for what will likely be a lengthy recession, what lessons has the sector learned from the crisis so far, and what are the plans and fears for the future for those working within it?

Alcohol and drug addiction recovery services around the country have been under pressure, fragmented and lacking consistency for a long time.” It was a statement few working in the sector would disagree with.

Made by Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern in July while announcing $32 million of funding for alcohol and drug addiction services in Napier, both Ardern’s words and the funding boost itself could be interpreted by the cautiously optimistic as a sign Covid-19 won’t lay waste to long-overdue plans to significantly boost funding in the sector, which kicked off with the well-received inquiry report into mental health and addiction He Ara Oranga in 2018.

For the slightly less hopeful, there are already fears these plans will not be realised, as the sector readies itself along with the rest of the country for what could be a lengthy recession. Some economists are warning that, despite the current situation looking less grim than initially forecast, we should expect a “W-shaped” recovery. Another slump will come as the wage subsidy expires, and disruptions in the global economy will continue to affect New Zealand domestically well into next year and beyond, even if we have continued success in eradicating the coronavirus domestically.

For those working in addictions, a recession creates two threats that, while separate, feed off one another: funding freezes and more people seeking help for harmful drug and alcohol use. At the same time as the government of the day is likely to be looking to cut back on its spending, people who have been out of work, stressed and struggling are more likely to develop harmful habits with alcohol and drugs (the immediate impact of a crisis like lockdown or the pandemic is more mixed in how it affects people’s substance use). This is broadly the lesson learned from the global financial crisis (GFC) in 2008, although there are difficulties with quantifying cause and effect exactly.

That said, the sector is sitting in an interesting space right now. The months spent working from home earlier this year have changed the way parts of the sector deliver services as well as revealing certain structural inequities clients are dealing with, which need to be addressed. While holding concerns for how the next months and years might play out, there is also a sense among those in the sector that the challenges of lockdown have shaken things up in a good way.

PM Jacinda Adern speaking at a podium with NZ flag behind her - Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern. Photo credit: AP Nick Perry

Lessons from lockdown: The opportunities and limitations of digital service provision

In a survey of the addiction sector conducted in May by Te Pou, nearly three-quarters (73%) of respondents said benefits experienced in lockdown related to adapting service delivery, for example, exploring virtual one-on-one sessions or online support groups. Other benefits cited were improved flexibility for sector workers and clients and improved collaboration between services. There is a general sense that the sector has made huge strides in embracing digital technology, tapping into previously unexplored potential.

“The addiction sector had been tentatively exploring how they could reach and engage people through technology for years,” Ben Birks Ang of the Drug Foundation says. “This situation meant that the sector needed to move quickly, and we ended up with the most online support being available for people with addictions in our history.

“We heard stories from AA and New Zealand groups who were used to seeing small groups of people from their local community, and then suddenly they were connected to larger groups of people from around the country.” There was also a sense of becoming more connected with local iwi.

Richard Taylor, who works in mental health and addiction for the Ministry of Health, says the shift is incredibly encouraging. “It’s [supporting people online or over the phone] something the health sector generally has talked about for a long time but never done on this scale - and what we’ve got now is practice in making it possible.”

Sue Paton, Executive Director of Dapaanz (the professional association for people working in addiction treatment), sees the quick adoption of entirely new systems as confirmation of the resilience and flexibility of the sector and those who work within it.

“The addiction sector really stepped up in terms of adapting and innovating in terms of connecting with people during lockdown”.

... that was a real shock in terms of the inequality and the poverty people were living in.”

For example, people from deprived rural areas often face access barriers. They may have to travel an hour and a half to see someone, but they can’t afford to run a car and there’s no public transport where they live. The realisation during lockdown that many clients were open and responsive to video meetings or phone calls was a positive discovery, and the sector will be looking to lock in those gains by supporting communities to develop digital practice where it doesn’t yet exist and also develop more flexible practice amongst the workforce, Taylor says.

The pivot to digital wasn’t without its problems though. Those with addiction issues are not infrequently dealing with other structural inequities, and like dye splashed over white crayon, lockdown starkly revealed problems service providers hadn’t necessarily grappled with before.

Something as simple as having access to a topped-up phone was not the case for every client. The response within the sector was to provide as many clients as possible with phones and data packages, but there wasn’t always the funding available within services to provide this help. And despite its seeming ubiquity in modern life, not everyone has reliable internet access. The 2018 Census showed there were still more than 200,000 houses in New Zealand without internet access – a statistic that correlates with low income.

Te Ara Oranga, a Northland DHB service that partners with Police to make health interventions in cases where people are struggling with meth use, noted the mid to far north of the country was particularly impacted by lack of internet access. Access to services during lockdown was provided in these areas mainly by phone, although patchy mobile reception and clients’ access to phones was also an issue. During lockdown, community resources such as computers at local libraries were not available, meaning lack of access from a personal phone or computer became a more pronounced issue.

Richard Taylor - head shot - Richard Taylor, Ministry of Health. Photo: Supplied

In the Te Pou survey, lack of access to computers, phones or phone data for clients and the addictions workforce was the most commonly mentioned challenge during lockdown, with more than half (65%) of respondents citing it as an issue. “People knew [some clients] didn’t have a lot of money, but I think that was a real shock in terms of the inequality and the poverty people were living in,” says Marion Blake, CEO of the community sector support organisation Platform.

There was also evidence as soon as lockdown started of real food poverty amongst clients (or whaiora), so support workers started delivering food parcels to those in need. New systems were developed to do what needed to be done immediately irrespective of what people’s normal jobs were.

During lockdown, some whaiora were scared. They weren’t clear on when they could leave their homes, and they didn’t want to get sick. Some wouldn’t answer the door to workers checking in, thinking they had to wear a mask even if they were standing two metres away. Clear communication was needed, which wasn’t necessarily reaching some people via government messaging. Service workers were not only helping with addiction treatment or delivering phones and food, they were also reminding people to keep washing their hands and managing some clients’ feelings of deep isolation.

“We’re not going to app our way out of a crisis.”

Marion Blake, CEO Platform“Any time there’s some kind of crisis event, the impact is always on already vulnerable citizens and communities,” Paton says. “The addiction sector at the moment is not set up to really support people more holistically. But I do wonder, moving forward, if we do need to think quite deeply as a sector about social justice issues and what our roles are in these issues.”

Taylor makes a similar point. He says mental health and addiction services have to be conceptualised within a broader context to address social inequity – something the government’s Psychosocial and Mental Wellbeing Recovery Plan, created in response to the pandemic, also acknowledges. “There’s an old saying that mental health and addiction is everybody’s business, and actually we’re talking about social determinants of health.”

Blake points out that, despite the opportunities digital services offer, “we’re not going to app our way out of a crisis”. The plan now should be about expanding the toolkit, not replacing the tools we already have. Digital alternatives for traditional service delivery could be appealing (especially amidst worries of future funding freezes) because they were often cheaper, but to rely too heavily on digital as a catch-all solution would be a mistake.

There’s a risk too that service providers could latch on to cheaper alternatives without considering whether they were really better for clients, Paton says. Yes, some clients, particularly young people, preferred online services and actually felt more connected using them. Others felt a phone call was less intrusive than a home visit, “but it’s not everybody’s cup of tea”.

Sue Paton with green leafy background - Sue Paton, Executive Director of Dapaanz. Photo credit: Supplied

Lockdown and substance use

In terms of its impact on substance use, lockdown was a mixed bag: some people actually benefited from the disruption while others struggled. Sue Hay of the Salvation Army Bridge in the Northland region said, against all expectations, “tangata whaiora who had already engaged with us prior to lockdown, on the whole, reported they had done better under lockdown conditions. They were able to avoid contact with peers and associates who would normally encourage alcohol and other drug use. One used medically directed quarantine to self-detox off methamphetamine.”

A Te Ara Oranga spokesperson says this had also been the case for some of its clients, who reported using methamphetamine less during lockdown, possibly because of lowered expectations, less day-to-day stress and the social draw of drug use virtually disappearing. However, other whaiora experiencing a stressful lockdown relapsed after struggling to cope. Anecdotally, several programme managers reported hearing there was more trouble accessing drugs during lockdown, and drug seeking became more obvious during a period where people were expected to stay inside their homes and keep their distance from one another.

Anna Nelson, a Wellington social worker who manages an outpatient clinic, says that, among the general population, lockdown would have been like an extended version of New Year for some people. “You’ve had time to think about what your future holds and what you want with your life, and I guess it gave people the time to slow down and think about what they want from their life.” For people already seeking treatment, lockdown had variable effects, but some clients saw a really positive impact. “Given the heightened anxiety generally in the public going into lockdown, the surprise for us was some of our clients were like ‘phew’. There was a relief – no one coming over, no expectations to go out and see people. For people with social anxiety, it was a nice break, and for some, that decrease in anxiety led to a decrease in substance use.”

Hay reports good engagement rates with clients over lockdown, noting that engagement was “perhaps higher than if tangata whaiora were engaged in normal life. There were not the usual barriers to access support in Northland in terms of transport, childcare or other competing demands from whānau or work.”

Although referral numbers for that service are higher now than pre-Covid, it’s hard to know yet if this reflects increased demand or simply represents those who would have presented during April and May, she says. “It’s too soon to make predictions regarding future demand trends.”

This variability in responses is also borne out in a survey conducted among the general population by Nielson for the Health Promotion Agency, which found one-fifth of respondents increased their drinking over lockdown, one-third decreased their drinking and just under half reported no change. This survey and another taken by the Drug Foundation in New Zealand during lockdown, as well as a study by the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction in June, show that, among people whose substance use has increased since the Covid-19 pandemic began, the main drivers were anxiety and boredom. The most common substances used in these cases were alcohol and cannabis, although some areas of Europe showed an increase in methamphetamine use.

Marion Blake head and shoulders - Marion Blake, CEO Platform

What a recession means for substance use and the addiction sector

There’s no one story for how people’s substance use is affected by life events. It’s more like a multiple-path story with nearly infinite potential outcomes. Because of how we each individually respond to stress, it’s possible that, for one person, a crisis (like a global pandemic) would prompt them to stop drinking entirely, while for another, their recreational drug use might increase under pressure. Some people will respond to the long-term stress of a recession (losing a job with reduced chances of getting another one or keeping a job but witnessing multiple rounds of redundancies) by increasing their substance use, and it’s over this longer period that harmful use can entrench itself as addiction. People more vulnerable to this are likely to have already been regular substance users. Maybe they’ve always used alcohol as a social crutch, or perhaps they’ve smoked cannabis to relax for years but now find they rely on it more and more frequently. On the other hand, people who use alcohol very infrequently (maybe they have a wine or two a couple of times a month) tend to respond to actual or threatened financial instability by using substances even less frequently.

Increases in things like domestic violence, petty offending and driving offences are often reliable indicators that harmful substance use is increasing in the wider community, addiction specialists say. When there’s a crisis, the most vulnerable are hit hardest, and a minority of people will lash out as a result, Paton says. “We know these crisis events escalate issues we already have in society. Some people don’t have access to the resources, they’re already in a position where they have less access to resources, they’re [already] more likely to come into contact with Police. Then potentially losing a job, being locked down, it adds stress.

“If you’ve got a guy who’s lost his job, he’s lost his income, he’s lost his mana, he’s really stressed out because he’s got his partner and three kids – there’s a minority of people that will lash out.”

Ashley Koning, an addiction specialist with more than 30 years’ experience in the sector, says the tell-tale social trends take a while to appear, and whether they will after this crisis depends in part on how bad unemployment gets. “If that 10% figure [of unemployment projection is reached], then we’re going to see this stuff kick in in six months to a year.”

The recession won’t only impact the addiction sector in terms of increasing people’s substance use – recall that some people choose to stop drinking or using drugs when money gets tight. It’s possible there will also be an increase in treatment seeking as people become unable to afford drugs such as meth any longer and instead look for help to kick their habit. “That’s possibly likely to have an impact on mental health services as well, because often the treatment seeking manifests as things like depression or anxiety.”

“If you’ve got a guy who’s lost his job, he’s lost his income, he’s lost his mana, he’s really stressed out ... there’s a minority of people that will lash out.”

Sue Paton, Executive Director DapaanzNot everyone who stops drinking will seek treatment, and some will use online tools like the forum Living Sober or local NA or AA meetings instead of seeking more serious interventions like residential treatment. Taylor says the addiction sector was already thinking about how to expand services to offer more to people who don’t need full-on intervention like residential treatment but want a hand getting their substance use under control. “It was clear from He Ara Oranga that people weren’t accessing the help they needed until they got to a crisis.”

If communities can be supported to be resilient and help is offered to treat people’s anxiety and depression for example, it is possible to intervene before addiction sets in, Taylor says. While there is inherent good in helping people before their needs escalate, there is a secondary benefit in that it reduces demand on more intensive services, many of which are limited, and ensures these specialist services are available when people need them. “Yes, services need additional support and we have funding coming through, but [with He Ara Oranga’s guiding principles, we’re] also trying to reach people earlier so that challenges can be dealt with before they get bigger and more complex to resolve.” Initiatives including increased peer support within communities and more widely available counselling were all part of the plan to make this shift.

This is important, as the sector as a whole will struggle to cope with even a 10% demand increase, Koning says. He points to the He Ara Oranga report as proof of service workers’ claims they are already working at full capacity and beyond. Part of the issue is also that there are not enough people training to work in the addiction sector, which limits the effect of increasing services even if money is allocated for this. “There isn’t a not working addiction workforce out there. We’ve got to grow the workforce, which does mean training people.” The Ministry of Health has addressed this issue with the Mental Health and Addiction Workforce Action Plan 2017–2021, and there was allocation in this year’s budget to train new counsellors, although this was not addiction specific. Addiction practitioners who have a counselling degree would need an additional addiction qualification (plus supervised experience as an addiction practitioner) before being registered as an addiction practitioner.

Increasing the workforce requires not just funding but addressing stigma about addiction within the wider medical community, Koning says. He also recommends tapping into the potential of the peer workforce and thinks the government could encourage this through schemes or incentives.

Ashley Koning head and shoulders - Addiction specialist Ashley Koning. Photo credit: Supplied

Fears and hopes for the future

There was a general consensus that the addiction sector runs more or less on the smell of an oily rag even in good times and that government belt tightening during lean times has typically been experienced as more of a freeze or pause on any increase in funding rather than cuts to funding for services.

Those working in the sector generally held the view that the crisis of Covid could well redirect funding previously earmarked for addiction services in next year’s Budget to other areas – a disappointing, if understandable, outcome. Optimism and hope that followed the government’s 2019 commitment to He Ara Oranga has now faded slightly for some. Taylor holds a more optimistic view, pointing to the $32 million funding boost in July as a good sign and committed increases to funding from Budget 2019.

Covid presents an ever-changing environment, but nevertheless Taylor says that “we’re looking at the model of care for alcohol and other drug services and part of that is looking to guide our current and any future investment in the best way possible.”

The Psychosocial and Mental Wellbeing Recovery Plan, published in mid-May by the Ministry of Health, is also encouraging in that it makes many references to the importance of wellbeing in the post-Covid recovery. On page 17, the report states: “COVID-19 has presented additional challenges for the mental health and addiction sector, with the transformation called for by He Ara Oranga now even more critical [emphasis added]. Many wellbeing stakeholders recognize the opportunity presented by COVID-19 to pause and re-evaluate to ensure this transformation is relevant to our current circumstances.”

One part of the report outlines addiction and mental health support as a specific focus area: “Strengthen primary mental health and addiction support in communities … While this work was under development prior to COVID-19, increased mental wellbeing needs due to the pandemic will elevate the importance of this focus.”

Further down it reads: “Kaupapa Māori services, designed by and for Māori, will be expanded. Effective evaluation and workforce support will supplement this focus area. Services will be designed collaboratively, including input from people with lived experience of mental health and addiction services.”

“It’s going to be much more attractive to rehome nice white middle class families than it is for people with substance use who live on the margins.”

Marion Blake, CEO PlatformPaton is cautiously hopeful this is a good sign with regards to future funding, and it meets the expectation of Northland’s Te Ara Oranga organisation that the government must continue to “promote confidence that mental health and addiction is still a priority”.

During the recession following the 2008 GFC, Paton remembers how people seeking addiction treatment from various programmes or organisations were showing up with more complex needs than usual – they were more likely to have co-existing mental health issues or problems with unemployment or housing, they were more likely to be suicidal. “You’ve got services who are expected to do more, because people are particularly unwell because of the circumstances and the stress,” she says. This can mean it takes them longer to go through treatment, which has the knock-on effect of making it more difficult to get people with less-complex needs into treatment before their problems accelerate.

Blake proposes a theory that the wider impact of Covid-19 could actually be good for funding because more middle-class people may start seeking treatment for the first time. The sector was expecting an increase in mental distress in the short and medium term and to see it from “a very different population”.

“We’re seeing it from people who have had jobs, who have got housing security at the moment, although that becomes vulnerable as people don’t have so much money. I think because it is a different population, we will see different responses from the system. Many of the issues that people who have had jobs and are now unemployed are raising is exactly the same thing people who have been unemployed for a long time have raised.”

Her fear is that help will arrive but be distributed inequitably, and the most vulnerable among us will be shunted to the back of the queue. Long-standing efforts to get people with complex mental health and addiction needs into homes and jobs may be deprioritised in favour of “relocating baristas”, she worries. “It’s going to be much more attractive to rehome nice white middle class families than it is for people with substance use who live on the margins.”

This is one way a recession can undo good work. “A lot of us have worked very hard to raise the profile of people living with chronic mental illness and addiction issues,” Blake says. The discussion now is on general wellbeing and distress, which shifts the focus away from those who are acutely unwell to a wider group of the population – a group it is much easier to assist. The Te Ara Oranga spokesperson also points to the possibility that those struggling with recent unemployment may themselves deprioritise addiction treatment during a recession.

It’s possible new systems will be put in place to help the newly unemployed and distressed middle classes, while the mental health and addiction system for people with complex needs remains “chaotic” and underfunded. “These are entrenched social issues, and they’re not going to go away in the blink of an eye,” Blake says. “Our addiction services are small, they are unsupported. We’ve got to find different ways of doing things.”

Like so many parts of life post-Covid, the sector will have to wait and see what the ‘new normal’ looks like.

Recent news

Beyond the bottle: Paddy, Guyon, and Lotta on life after alcohol

Well-known NZers share what it's like to live without alcohol in a culture that celebrates it at every turn

Funding boost and significant shift needed for health-based approach to drugs

A new paper sets out the Drug Foundation's vision for a health-based approach to drug harm

Expert Pharmac committee recommends funding for overdose reversal nasal spray

The expert committee has said funding for naloxone in the community should be a high priority