Could regulating MDMA make it safer?

In Aotearoa, MDMA trails only alcohol, tobacco, and cannabis as New Zealanders’ drug of choice. While many countries are currently reconsidering the criminalisation of drug use, in New Zealand, possession of MDMA, a relatively low-harm substance, may land you with up to three months in prison. Recently, Australia’s Therapeutic Goods Administration changed regulations, opening the door to psychiatrists prescribing MDMA and psilocybin for treatment-resistant mental illnesses. Meanwhile, the Australian Capital Territory has passed a law decriminalising possession of most controlled drugs.

Given MDMA’s popularity, potential therapeutic uses, and low harm profile, is it time we re-examine how we regulate it here? Drug Foundation Senior Communications Advisor Feilidh Dwyer investigates.

A brief history of MDMA

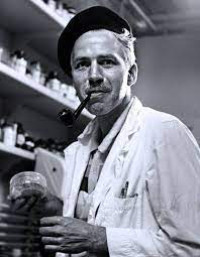

In 1912,German drug manufacturer, Merck, patented a chemical compound called MDMA (methylenedioxymethamphetamine) to make medicine to control bleeding. For sixty years, it remained relatively unknown until, in the late 1970s, pharmacologist and psychedelic researcher Alexander Shulgin (pictured in the 1960s) resynthesised and experimented with it on himself, noting its ability to produce an "altered state of consciousness with emotional and sensual overtones."

When consumed, MDMA floods the brain with serotonin, leading feelings of euphoria, increased empathy, and connectedness. In the late 70s, a group of US psychiatrists began prescribing it to patients describing it as a "penicillin for the soul," and by the mid-1980s, it had become popular in New Zealand’s nightclub scene. In 1985, the US outlawed MDMA and in1987, New Zealand followed suit.

At present, selling or supplying MDMA is punishable by up to 2 years in prison.

Most MDMA purchased in New Zealand originates from Europe. In NZ, a single MDMA pill generally costs between $30-40, with the median price per gram costing around $200-250.

Who takes MDMA?

MDMA is extremely popular. A 2020 Global Drug Survey of 110,000 people in 25 countries, found MDMA is the fourth most consumed drug worldwide. In Aotearoa, Police wastewater testing from Quarter 4 2022,reveal that although MDMA is widely taken throughout the motu, per capita it is most heavily consumed in the Southern (including Dunedin and Invercargill) and Wellington regions.

Chair of KnowYourStuffNZ (KYSNZ), Wendy Allison, says the popularity of MDMA in New Zealand’s festival scene is expected.

“In a world where people are feeling increasingly disconnected from each other and our communities, it's unsurprising that a substance that enhances feelings of connection and community, and creates mostly positive social experiences, is popular,” she says.

“People [tell us] it's cheaper than alcohol with a lower calorie intake, and the after-effects are less unpleasant.”

Jai Whelan (pictured), an Otago University psychology PhD student, recently conducted the largest national study of MDMA use in New Zealand. His study interviewed 60 New Zealanders in person and another 800 completed an online survey.

The study found that Kiwi MDMA users are diverse. Whelan’s respondents came from across the country, were aged 18-67, and used MDMA for a variety of reasons, typically in social settings such as festivals or parties.

“Many people spoke of finding benefits from MDMA that went beyond the trip, including strengthening friendships and emotional availability and being a nicer person,” Whelan says.

“It’s not like people get sucked in, or however you want to frame it. The benefits…are impactful on some people’s lives.”

Although the majority of respondents in Whelan’s study reported enjoying the experience with friends and encountered no negative consequences, some suffered anxiety and the comedown afterwards often left them feeling tired with a low mood.

Image of people at a festival

What are the risks?

Taking MDMA can increase heart rate and blood pressure, potentially leading to overheating, dehydration light sensitivity, impaired judgement, anxiety, jaw clenching, and shortness of breath. Rarer but severe risks involve serotonin syndrome, a life-threatening condition caused by excessive serotonin levels, and hyponatremia, a dangerous state where the body's sodium levels become too low. To find out more about the risks, see The Level.

According to a 2010 Lancet journal study in the UK, MDMA ranks below alcohol, tobacco, cannabis, and others, making it one of the least risky recreational substances. New Zealand clinical toxicologist and emergency medicine specialist, Dr Paul Quigley, has gone on record saying when MDMA is taken at appropriate doses, it is relatively harmless.

Overdoses do happen, but they are very rare. Sadly, a small number of New Zealanders have lost their lives after taking MDMA. From the data we have, between 2017-2021, 12 people who died from overdoses had MDMA in their system. In all but one of those cases, toxicology reports showed the presence of other drugs in the person’s system.

Wendy Allison says MDMA’s illegal status means there is a serious lack of easily accessible information about it out there.

“Many KYSNZ clients have little knowledge of the drugs they were taking or harm reduction principles…[they] generally don't know about the impact of MDMA on the serotonin system and how long it takes for depleted serotonin to rebuild in the body after using MDMA.”

“This leads to people taking it several times in a weekend, or week after week, without knowing that they should give their body a break,” she says.

Therapeutic uses of MDMA

Although primarily used recreationally, MDMA has multiple therapeutic applications, particularly in the treatment of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). When used in combination with talk therapy, it has been shown to be well tolerated and effective in reducing PTSD symptoms without the side effects of some other prescribed medications. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is expected to approve MDMA for therapeutic use in 2023.

In addition to its potential in treating PTSD, MDMA has also been shown to help those with Alcohol Use Disorder reduce their consumption and helped autistic adults reduce their social anxiety.

Associate Professor Fiona Hutton at Victoria University's Institute of Criminology has focused much of her academic research on harm reduction and drug policy. She believes MDMA-assisted therapy could be beneficial for New Zealanders if it was legal and widely available but cautions that it should be properly integrated with talk therapy.

Hutton notes that psychedelic/MDMA-assisted therapy is not a magic bullet and may not suit everyone. Proper training and regulations are necessary to ensure its safe and effective use.

Our current drug laws

New Zealand’s current drug laws treat drug use as a criminal offense rather than a health issue. MDMA is currently a Class B drug under the Misuse of Drugs Act 1975.

Executive Director of the New Zealand Drug Foundation, Sarah Helm (pictured left), emphasises that regulatory settings should reflect the relative harm of each substance, and that the science shows that MDMA is at the lower end of harm.

Although the government changed the law in 2019 to give police more discretion over whether to prosecute people for personal possession of drugs, many individuals still face prosecution for simple possession and use of various substances. The threat of criminalisation creates other problems, including an inability to know the potency of what is being consumed.

Helm points out there is an assumption that banning substances makes them safer and that it discourages use, but that the opposite is actually true for MDMA.

“In fact, regulatory tools are incredibly helpful in protecting the public from harm. We see that with a range of issues that cause harm from tobacco to asbestos,” she says. “The lack of regulation of MDMA is one of the greatest risks to people who use it, that they cannot be certain of what is in it, nor its potency.”

Seizing MDMA doesn’t reduce MDMA use – but it does increase harm

With other substances being cheaper or easier to import or manufacture, a significant percent of "MDMA" sold in New Zealand is actually something else, like synthetic cathinones, also known as bath salts. Synthetic cathinones, such as eutylone, are a large group of manufactured stimulants created to mimic the effects of other substances. They can cause seizures, anxiety, and psychosis and are a potentially dangerous imposter for MDMA.

In 2022, the Drug Foundation found that 18% of presumed MDMA brought into their drug checking clinics was either mixed with another psychoactive substance or was another substance entirely.

One of the biggest problems with prohibition is that our drug laws are intended to reduce harm but often end up causing more harm than good.

Wendy Allison says that a perverse outcome arising from New Zealand’s current approach to MDMA can be that the more of it Police and Customs seize of it, the more fake MDMA that circulates around the country, causing more harm than the real deal.

To reinforce this point, in 2020, police seized 339kg of ecstasy, but that year, KYSNZ reported that more than half of the MDMA they checked at festivals was actually synthetic cathinones.

Allison points out that unlike in a regulated market, an illicit market has no quality controls or consumer support. This makes it open to unscrupulous people selling things that are not as advertised, with no comeback.

Other problems with the status quo

Another significant drawback of drug prohibition is the stigma surrounding drug use. Despite the fact that almost half of New Zealand’s adult population have tried an illegal drug at some point in their lives, drug-related stigma remains a pervasive issue.

Although MDMA is a drug that causes lower levels of harm compared to other substances, for people struggling with substance use issues generally, prohibition often deters them talking to others about it or seeking help due to their fear of judgment or legal consequences. A regulated system with better health pathways and information would substantially reduce the influence of stigma. This would help facilitate honest discussions and education about drugs, ultimately leading to more informed and safer drug use and reduced community harm.

Lastly, drug prohibition hinders research and access to legal therapeutic approaches, as Fiona Hutton explains. Given the significant body of international research showing how MDMA can provide treatment and relief for people dealing with a raft of health issues, particularly PTSD, she says a properly developed legal therapeutic approach to MDMA is needed. Hutton suggests that people experiencing mental health challenges and PTSD should be supported in seeking appropriate and legal avenues for obtaining medicinal MDMA, rather than having to resort to the illicit market.

A better path – the benefits of a regulated MDMA market in Aotearoa

Instead of continuing to perpetuate a harmful status quo, New Zealand has the opportunity to explore alternative, health-based, harm reduction approaches to regulating MDMA.

Although several countries have decriminalised MDMA, none have established a regulated market.

Wendy Allison supports full legalisation of MDMA in Aotearoa. She would like to see a regulatory framework that permits it to be sold to adults in specific quantities, at consistent purity, with quality control, labelling, and for it to be covered under the Consumer Guarantees Act.

“Fifty years of prohibiting substances has not reduced use or harm, therefore retaining prohibition is pointless if harm is what we care about,” she says.

She believes that while decriminalisation at user level would be a step in the right direction, it would not address problems with the illicit market.

“The harms that are associated with MDMA can be more readily addressed by regulation of the supply chain, which can only happen if it's legal.”

Helm agrees.

“The regulation of substances is far more effective at reducing harm than prohibition is,” she says. “New Zealand currently wastes a tremendous amount of money charging and criminalising people for using drugs. That money could be far better spent elsewhere on, for example, proper drug education and treatment.”

If MDMA were legalised and regulated, Allison says KnowYourStuffNZ would no longer be needed.

“In the same way that we don't need a KYSNZ for alcohol to make sure people don't end up drinking turps.”“We would like nothing better than to be made obsolete by good drug regulation that actually works to reduce harm.”

Interested in reading more on MDMA regulation? Check out our previous Matters of Substance article focused on an MDMA ‘popup shop’ in the Netherlands which explored drug regulated supply.

Recent news

Potentially lethal dose of methamphetamine found in Rinda pineapple lolly wrapping

The Drug Foundation is warning people not to consume Rinda pineapple lollies.

Beyond the bottle: Paddy, Guyon, and Lotta on life after alcohol

Well-known NZers share what it's like to live without alcohol in a culture that celebrates it at every turn

Funding boost and significant shift needed for health-based approach to drugs

A new paper sets out the Drug Foundation's vision for a health-based approach to drug harm