Face Trashed

Alcohol marketing on social media is cheap, successful and legal. But researchers say New Zealand should be attempting to control marketers’ sophisticated digital strategies to build brand loyalty with young Kiwis. Keri Welham reports.

There are more than 1 billion people on gargantuan social media network Facebook.

It can serve as a social organiser, a way to quickly share family photos, an address book, a device to track down old mates and – crucially for young people – an opportunity to create and refine an online persona.

When young people ‘like’ their favourite fashion designer, coffee house, musician or sports team, it clarifies their desired social standing. They know their friends will see content posted by the brands they’ve liked. Glassons or Karen Walker? The Eagles or Paloma Faith? Badminton or cage fighting? Southern Comfort or Tutankhamun Ale?

An enthusiasm towards drinking can be communicated by liking alcoholrelated pages or brands. Teens and young adults will be among the 5.2 million people who like a Facebook page called Beer, the 5.3 million who like the ‘hobby’ drinking or the 51,000 who like the ‘sport’ drinking.

In December last year, Facebook announced it had 1.23 billion monthly active users. The other big players at this stage are Twitter, Instagram, YouTube, Snapchat, WhatsApp and, for the oldies, Pinterest and LinkedIn. The sites most commonly linked to alcohol marketing are Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

In an unprecedented move, Finland will introduce alcohol advertising reforms from 2015 that are aimed at limiting social media marketing.

But New Zealand beer brands have had considerable success with social media marketing in recent months – with campaigns such as Tui’s Catch a Million – and advertising bodies would strongly oppose similar moves here.

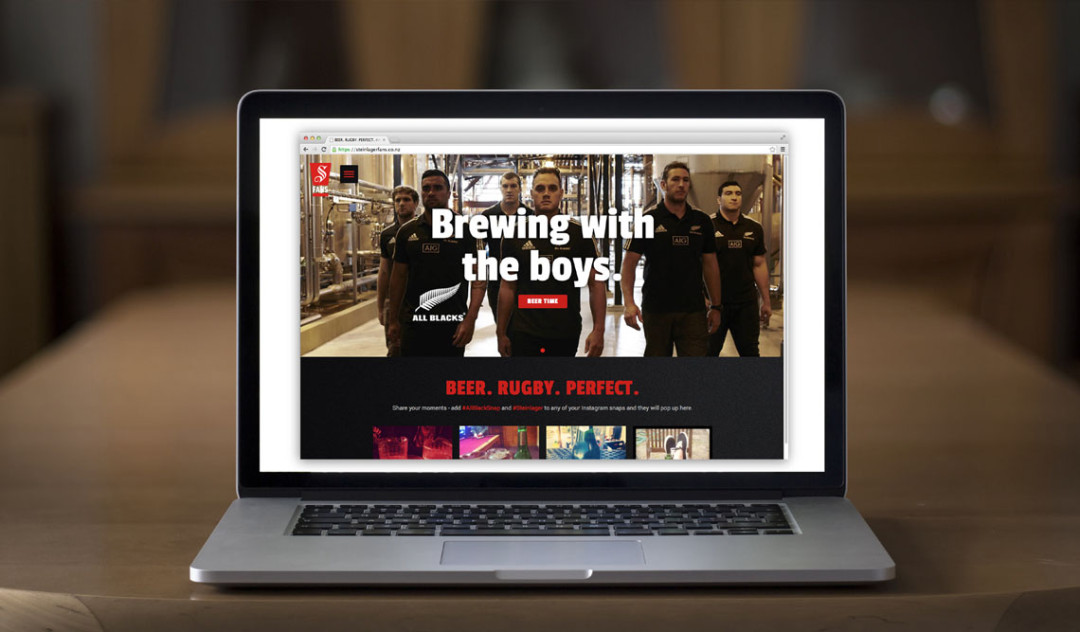

Steinlager’s #AllBlackSnap was digital marketing gold for the beer brand. A columnist on marketing publication StopPress suggested it was “either a slightly duplicitous or very clever way of getting the people to post ‘ads’ for Steinlager of their own volition”.

StopPress explains that the Steinlager campaign was launched for the first 2014 All Black test against England at Eden Park on 7 June. Rugby fans were invited to post pictures of themselves at the ground with a numbered Steinlager bottle (one for each member of the team) and the hashtag #AllBlackSnap. When Aaron Cruden scored the first goal wearing the number 10 jersey, prizes were immediately delivered to some of those who had posted images of themselves with number 10 bottles.

StopPress says the campaign generated a combined social reach of more than 350,000 from a total of 1,300 entries on social media sites Twitter, Facebook and Instagram. Some of this consumergenerated content was then loaded onto the site steinlagerfans.co.nz, under the headline: BEER. RUGBY. PERFECT.

So, what?

Is there anything wrong with a Kiwi sports fan who enthusiastically uploads pictures of themselves with sponsor’s product in the hope of winning merchandise?

What about a New Zealander of legal drinking age who willingly shares a viral video or photo created by an alcohol marketer?

Or a pic, uploaded to a beer brand’s Facebook page, of an infant with an empty beer bottle?

Massey University Associate Professor of Psychology Antonia Lyons studies New Zealand’s culture of intoxication.

“Research has shown that [alcohol marketing] is very harmful,” she says. “It reinforces a drinking culture.”

Last year, Lyons led research into drinking cultures and digital technologies. A report, titled Flaunting it on Facebook: Young adults, drinking cultures and the cult of celebrity, was released in March this year. It covers surveys of 141 young adults, analysis of 487 examples of online marketing and a walk-through of 23 individual Facebook users’ pages.

The report says young New Zealanders are obsessed with identity, image and celebrity.

“Being visible online was crucial for many young adults, and they put significant amounts of time and energy into updating and maintaining Facebook pages, particularly with material regarding drinking practices and events,” says the report.

“Alcohol companies employed social media to market their products to young people in sophisticated ways that meant the campaigns and actions were rarely perceived as marketing. Online alcohol marketing initiatives were actively appropriated by young people and reproduced within their Facebook pages to present tastes and preferences, facilitate social interaction, construct identities and more generally develop cultural capital.” Lyons says researchers were shocked by the volume of alcohol marketing in social media.

“You see the desire to get intoxicated become normalised.”

This is evident on pages like Getting Drunk!, which has almost 700,000 likes and is updated with new alcohol-related jokes at least once a week.

No single company stands to gain from a page like Getting Drunk!

But sophisticated brands pour significant budgets into digital marketing in an attempt to garner followings comparable in size to those on the joke sites. They post well devised videos with excellent filming and make it easy for consumers to share the videos with their online friends.

For brands, viral posts lend a valuable impression of personal endorsement to advertising material. And in terms of the bottom line, marketing becomes extremely cost-effective when consumers themselves take care of message dissemination.

Research by Dr Nicholas Carah at the Australian Foundation for Alcohol Research and Education (FARE) shows Australia’s top 20 alcohol brands posted more than 4,500 items of digital marketing content on Facebook in 2012.

“Brands continuously seek engagement from fans in the form of likes, comments and shares. They ask questions, host competitions and post memes and videos to spark engagement and conversation. As brands do this, they rely on fans to use their own identities and peer networks to circulate brand messages.”

The research, released in May this year, shows brands are most likely to post social media content between 3–5pm on a Friday and will often reference end-of-the-week drinking rituals.

“Brands engage with consumers’ routine conversations about everyday life. The more embedded in everyday life alcohol consumption is, the more valuable alcohol brands are because they become increasingly impervious to regulation,” Carah writes.

Researchers from the University of Western Sydney’s School of Business studied six months of alcohol promotion on Twitter. They looked at the seven most valuable global alcohol brands and found, although each company’s Twitter following was modest (Heineken had 58,777 while pop star Lady Gaga has 42 million), their posts were often retweeted to a much larger secondary audience, which could include those under 18.

Lyons says those in her study drank to feel alcohol’s effects.

“People enjoy the buzz. It’s a positive experience a lot of the time,” she says.

“But it turns very quickly into a negative impact.”

She says social media offers an “airbrushed” drinking culture. It’s glam, funny, fun.

People seldom post about getting their stomach pumped or ending up in hospital after a fight, and posts about alcoholfuelled domestic violence are rare.

Lyons, Carah and other researchers say alcohol companies’ use of social media to create brand value has become a matter of public concern and debate.

But how, in practice, do you stop a runaway train of this magnitude?

Lindsay Mouat is Chief Executive of the Association of New Zealand Advertisers (ANZA). He says advertising portrays responsible drinking.

Advertisers are required to present drinking as an adult activity, enjoyed in moderation. The point of advertising is not to increase the volume of alcohol sold in New Zealand, he says, but for the brand in question to increase market share.

ANZA administers a service called the Liquor Advertising Pre-vetting System (LAPS – not to be confused with Local Alcohol Policies, which use the same acronym).

The LAPS, set up in 1998, offers advertisers an educated, external opinion on whether the campaign they are planning is likely to fall outside the Advertising Codes of Practice.

It is free to lay a complaint with the Advertising Standards Authority (ASA), of which Mouat is currently chair. A separate self-regulatory body called the Advertising Standards Complaints Board considers the complaints. It is made up of five public representatives with no connection to media or advertising groups and four ASA-nominated people with media and/or advertising backgrounds.

Since online records began in 2007, there have been 45 complaints to the New Zealand ASA regarding Facebook – nine of those involving alcohol companies or drinking establishments.

An explanation of the process on the ASA website illustrates the limited power at ASA’s disposal: “In the event of a complaint being upheld the advertiser, agency, and media are requested to withdraw the advertisement. These requests are invariably complied with.”

Mouat says complaints that are upheld bring “shame” on the advertiser in question.

On average, it takes the ASA 15 days to issue a decision. Antonia Lyons says this is an eternity in social media terms, where videos go viral in hours. Lindsay Mouat says 15 days is a fast turnaround for any adjudication process.

Mouat says, in recent years, there has been a marked reduction in the number of complaints about alcohol advertising to the ASA. He says it is assumed there are fewer complaints because advertisers are working within the guidelines.

In 2012, New Zealand passed section 237 of the Sale and Supply of Alcohol Act 2012. It implemented the first stage of the New Zealand Law Commission’s recommendations for alcohol law reform. This year, a Ministerial Forum on Alcohol Advertising and Sponsorship received submissions about advertising and promotion of alcohol. Submissions closed on 28 April.

In total, 177 submitters supported further alcohol advertising restrictions, while 64 submitters favoured the status quo. Not all submitters commented on both advertising and sponsorship.).

A summary of submissions states: “Generally, submitters categorised as health, professional associations, community/cultural groups, researchers, and individuals were more likely to support the implementation of further restrictions. Specific groups more likely to support the status quo (and no further restrictions) were sporting bodies, advertising/media submitters, retailers, alcohol industry and trade associations.”

The Health Ministry outlined three constraints that prevented consideration of further measures to address alcohol advertising and sponsorship. One factor was economic and community consequences as a result of lost sponsorship. Another was the difficulty of assessing the evidence base. The third factor was changing technology.

“It was noted that regulating alcohol advertising is difficult and its effect is uncertain, particularly because alcohol advertising is a rapidly growing area with new technologies and marketing techniques providing new opportunities to influence purchase and consumption behaviour. Restrictions, may, therefore, be easily circumvented.”

Antonia Lyons says: “So it’s too hard so we won’t bother? I mean, that’s a real cop-out. You could at least stand up and do something.”

In February this year, Finland introduced proposed amendments to alcohol advertising legislation. One of the new laws, due to take effect in 2015, is a ban on alcohol-branded social media communication.

Ismo Tuominen works on drafting the amendments. In a YouTube presentation, Tuominen says, in practice, the amendments will rule out any promotion involving a game, lottery or contest; advertiser use of any content produced by consumers; and production of viral marketing videos that are intended to be shared on social media.

In other words, various elements of the #AllBlackSnap promotion would be illegal in Finland.

The amendments don’t ban alcoholrelated posts on a consumer’s own website, social media page or emails, as these are not considered advertising.

Tuominen says he would have preferred more extreme regulations, banning everything except product information, but the political environment dictated that Finland should focus on banning the most harmful practices.

“Of course, the worst option, for any government, is just to sit back and watch these new forms of advertising,” Tuominen says.

Lindsay Mouat of ANZA says there is “complete stupidity” in what the Finns have done. “It will have very limited impact.”

What the legislation won’t stop, Mouat says, is young people taking photos of themselves drunk and posting them on their own social media accounts. Advertising-generated content would make up an “extremely small” part of a young adult’s newsfeed, as opposed to their friends’ posts about drinking.

“It’s not the advertising. It’s what their peers are doing.”

He says New Zealand’s legislative reform, similar to that in Finland, would “achieve absolutely nothing”.

“It’s just not going to help,” he says. “The media is changing so fast.”

Mouat points to France, where the Loi Evin alcohol policy law was introduced in 1991 to control advertising for alcohol. Mouat says analysis found it was “ineffective” in reducing high-risk drinking patterns.

However, alcohol prevention researchers said the legislation had brought about a distinct change in advertising. The Association Nationale de Prévention en Alcoologie et Addictologie (ANPAA) wrote that the success of complaints against advertisers, drawing on the strength of the law, had alarmed alcohol producers, advertisers and the media.

“As a consequence, since 1991, we can observe a real change in alcohol advertising: the law has modified the language of advertising, losing most of its seductive character. It is no longer allowed to use drinkers and drinking atmospheres: we have observed the disappearance of the drinker from the images and the highlighting of the product itself.”

A recent research letter in the Medical Journal of Australia referred to the success of banning tobacco promotion in 168 countries through the 2003 World Health Organisation’s Framework Convention on Tobacco Control.

“That framework’s trajectory suggests research, public pressure, political will and international co-operation are needed to reduce widespread alcohol promotion and the associated public health costs.”

Antonia Lyons says tobacco promotion reform was more straightforward because one cigarette is harmful, whereas one drink can have benefits. But she doesn’t believe that’s justification to avoid the issue of alcohol promotion on social media.

She would love to see social media companies like Facebook ban alcohol companies from advertising. But she’s pessimistic.

“It’s not going to happen.”

Lyons says Facebook makes too much advertising money from beverage giants like Diageo – makers of Johnnie Walker, Smirnoff, Guinness – to consider cutting off that income stream. (Diageo and Facebook signed a “multi-million dollar strategic partnership”, in September 2011, which aimed to “drive unprecedented levels of interaction and joint business planning and experimentation between the two companies.” Diageo reported that the partnership had led to a “20 percent increase in sales as a result of Facebook activity”.)

Lyons says a more realistic option is to make alcohol marketing transparent – so companies are forced to tell consumers they are watching/reading a paid advertisement. This might erode some of the social value for young people sharing advertiser-generated content. Lyons says the self-regulation model would need to be abandoned if demands and limitations on the industry were ever to be effectively enforced.

Lastly, Lyons would like to see advertisers forced to disclose what information they gather about consumers when their page is liked and how that information could be used to target drinkers.

“I can’t see that happening in New Zealand because the government hasn’t done very much about traditional alcohol marketing.”

She says any reform needs to be trans-national to be effective. Social media is global, so the solutions to a specific social media concern must be global too. Lyons says New Zealand is at “the very liberal end” of the alcohol regulation spectrum.

“We’ve normalised it so much that it’s part of everyday life. We can buy it at the supermarket. [But] it’s actually a drug and it’s a special commodity. It’s actually something quite unique.”

Keri Welham is a Tauranga-based writer.

Recent news

Beyond the bottle: Paddy, Guyon, and Lotta on life after alcohol

Well-known NZers share what it's like to live without alcohol in a culture that celebrates it at every turn

Funding boost and significant shift needed for health-based approach to drugs

A new paper sets out the Drug Foundation's vision for a health-based approach to drug harm

Expert Pharmac committee recommends funding for overdose reversal nasal spray

The expert committee has said funding for naloxone in the community should be a high priority