Getting real about synthetics

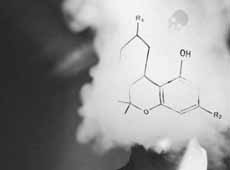

Naomi Arnold takes another look at our alarming death rate from synthetic cannabinoids and at some real-world responses from people working at the frontline. She renews the call for an early warning system but says we also need a more compassionate social approach that tackles why some of our most vulnerable roll the dice with this deadly substance in the first place.

July 2017 came with the shock news that seven sudden deaths in Auckland were linked to synthetic 'cannabis', and by September, that number had jumped to 20. Matters of Substance published several stories on the issue, calling it “an extraordinary spate” of deaths.

A year later, and things are even worse. The coroner now says 40–45 people have lost their lives to synthetic cannabinoids. That’s a huge jump on two deaths in the five years previous.

So what do we do now to tackle this urgent, increasingly deadly problem?

Some responses are already afoot. Back in July, Acting Prime Minister Winston Peters said urgent cross-party action was required, directing the Ministers of Health, Police, Customs and Justice to work on it together.

So far, several of the deaths are subject to a continuing joint inquiry, and no decisions have yet been made about a hearing.

“All of these cases have been assigned to Coroner Morag McDowell,” a spokesperson says, “to ensure all of the available information is before one coroner who can then liaise with other agencies.”

They say the office is working closely with the Ministry of Health, Police, district health boards, ESR and pathologists to identify the substances involved, and coroners will be providing updates as part of their role to prevent harm to the public. One approach has been to work with emergency departments to help them recognise when they are dealing with a synthetic cannabinoid and not another drug.

However, while the reports and discussions continue, people will still use – and die from – synthetic cannabis, and the impacts are seen daily by ambulance staff, medical staff, NGOs and community groups. What do those on the frontlines think the government should do in response?

Dr Tony Smith, in St John Ambulance uniform - St John Medical Director Dr Tony Smith. Photo credit: supplied.

Many of those spoken to for this story echoed the Drug Foundation’s ideal short-term response checklist, released in early August: fund central coordination of an urgent cross-agency response, focus on practical treatment and harm reduction interventions and implement an early warning system to coordinate information between Police, Customs, hospitals, ambulance staff, treatment providers, NGOs and ESR.

St John Medical Director Dr Tony Smith says it’s clear synthetic cannabinoids are causing more harm than any other drug and education is urgently needed on the drug’s propensity to kill. He says that, on the scale of individual harm that recreational drugs cause, synthetic cannabinoids come out on top.

“On a scale of 0 to 10, some [recreational] drugs are low and some are high in terms of risk,” he says. “I would say this drug is a 9.5 in terms of the danger of dying from it – and unexpectedly dying from it.”

Every person in cardiac arrest who St John has attended has been unable to be resuscitated.

We haven’t had a single survivor yet from cardiac arrest following smoking synthetic cannabinoids.

Dr Tony Smith, St John Medical DirectorWhat we don’t know is why one person can consume drugs from the same batch and be absolutely fine and the next person consumes the drug and just drops dead."

“We don’t know how many people consume it, so we can’t say that one in 1,000 people will die or one in 10,000 people will die … but we can put it into perspective with other drugs such as opiates like fentanyl, heroin and GHB [fantasy]. From an ambulance perspective, of the patients we are going to, this drug is causing more deaths than any other.”

St John receives about 30 callouts a week from people all over New Zealand who get in trouble after using it, with the biggest concentration of those in Auckland and particularly in the CBD. Those affected are from “all walks of life”, from teenagers through to people in their 60s.

Smith says St John would support measures that reduced the chances of people being able to buy it and also strongly support measures that educated people about the danger associated with these drugs.

“We’re not naïve enough to think people are going to suddenly stop consuming drugs tomorrow, [but] the message we are continually sending is, ‘This drug is dangerous, when you take this drug you roll a dice’. And, unfortunately, we are seeing people roll a dice, and the dice comes up that they’re going to die.”

Vicki Macfarlane - Vicki Macfarlane, addiction specialist and the lead clinician of Waitemata District Health Board’s Medical Detoxification Service.

For Vicki Macfarlane, addiction specialist and the lead clinician of Waitemata District Health Board’s Medical Detoxification Service, one of the biggest needs she sees is getting a drug-related warning system in place soon, so if people are arriving at emergency departments suffering effects from synthetic cannabinoids, it can raise the alarm.

“We need a better way of monitoring the numbers of people coming to various services and a really clear way of keeping track of who’s coming,” she says. “Ideally, we need a better way of identifying what substances people have been using. At the moment, it’s really slow and happens after the fact. Everyone responds after the crisis has already happened, and there is a lack of coordination in the response.”

She also wants to see treatment options improved to deal with the limited support currently available and examining in depth why people use such drugs.

“We need more information about why people are using it, how they are getting it and why they chose synthetic cannabis and not something else.”

She adds that it’s important for government to look at the social issues around the drugs – who is developing problematic use and how we can support those populations.

That’s backed up by Dr Nick Baker, a paediatrician and Nelson Marlborough Health Chief Medical Officer. He says any government policies to reduce drug harm should be focused on ensuring children have the best possible start to life to break the cycle of drug abuse.

“There are common journeys run by people who do end up badly affected by substance abuse,” he says. That can start before birth with poor antenatal care, which turns into parents unable to bond with their child “because they’ve never been bonded to themselves”.

“And so the baby has an infancy of adversity and doesn’t get warm fuzzies from having cuddles because they don’t get cuddles. They get warm fuzzies from [other] outlets,” he says.

“Better supporting parents to know how to relate to their infants and trying to get infants through their first 1,000 days in a better condition will actually have some impact on our long-term drug and alcohol usage.”

He says, as a paediatrician, it’s devastating watching cycles repeat.

“I might be caring for a young person who’s been subjected to child abuse, whose parents are drug and alcohol users, and they are having their own baby by the age of 15–16 who will in turn be subjected to domestic violence and drug and alcohol abuse, who will have their own baby thereafter."

Breaking the cycle is pretty important stuff.

Dr Nick Baker, Nelson Marlborough Health Chief Medical Officer.Baker says the right approach would be thinking about “the whole spectrum of prevention”, remembering that starts with the unborn.

“How do we best support mums having control over their own fertility to try and move towards every child being a wanted child? Then how do we support infants growing up so that they do not continue the cycle?”

That is what acts as the fence at the top of the cliff – further interventions later in life are the ambulance at the bottom.

“Sure, we can try and fence the cliff edge with legislation, but if the cliff edge is less attractive then you don’t need quite as strong fences. I think that would be one of my pleas: early intervention and giving people growing up a purpose in life.”

Baker agrees with Macfarlane in saying agencies need to share information better – “joined-up intelligence” that is ahead of the play and able to protect the community as problems emerge.

“What prospective surveillance is there in New Zealand to notice early if we do start to get a surge of young people experiencing sudden death? And how does Police intelligence share this with the National Poisons Centre and emergency departments? How does the emergency department share this with other groups? We’ve got to keep those feedback loops going, which try to help our community understand where the real hazards lie.”

That could also include screening people when they meet with health services for any reason – asking the right questions, directing them to the right support.

He also cites the success of Red Cross programme Save a Mate, which has been widely used for alcohol.

“Something really important is peer awareness,” he says. “When do you call an ambulance for your mate?”

However, despite anecdotal and media reports that people are using synthetic cannabis in place of the cannabis plant, he doesn’t favour improving access to cannabis itself.

“I think much more importantly we should be trying to support people who are often in the most deprived circumstances so that life is really worth living. I know from reviewing the deaths of young people who have died from substance abuse, particularly volatile solvents, that often it’s an escape from intolerable things. It hides the hunger pains, it hides the distress, it hides the unemployment. It masks the purposelessness of life.”

Moira Lawler, standing by Lifewise Trust sign. - Moira Lawler, CEO Lifewise Trust, Auckland. Photo supplied.

Out in the community, Lifewise Trust CEO Moira Lawler does favour decriminalisation. If she were Prime Minister tomorrow and could implement an emergency synthetic cannabis response, she would take away all penalties and exclusion of people who are unwell or using drugs. She says those only further hurt people who are already “completely on the margins”.

Together with Auckland City Mission, Lifewise runs a housing programme in Auckland, and Lawler says it’s time to take away the narrow lens that considers substance abuse in isolation. Instead, policymakers should consider what will best suit someone’s entire physical, mental and emotional wellbeing.

“People need access to services that can wrap around what they need right then,” she says. “Not a queue of linear services: ‘You can have that, then this, then the next thing’.

“We work with people every day who have developed an addiction as a result of their homelessness, so you really can’t discuss their addiction unless you are prepared to discuss their homelessness,” she says.

“We deal with people who are using very dangerous drugs because of their poverty levels, so you can’t really talk to them about their wellbeing unless you’re prepared to discuss their poverty.”

She says evidence shows a harm minimisation approach – which in part accepts that drug use exists along a continuum and is an inevitable part of society – is what’s most likely to help people improve their wellbeing, as opposed to compliance-based approaches. But although clinicians understand it, ‘harm minimisation’ is not a term that’s widely understood by the public, who see it as a soft option.

“I think it’s part of the culture we’ve grown over the past couple of decades – [that] the person who is on the margins of society has somehow done something to achieve that status.

Moira Lawler"So we have that blaming culture.”

In fact, she says, people with addictions are our most vulnerable and probably have been since childhood. But because the system doesn’t understand the complexity of their situation, they’ve ended up the most unwell and the least likely to be housed.

“These are the consequences of a system that lacks flexibility and responsiveness.”

Fixing that means listening to those who have drug addiction – having “a whole-person conversation”.

“The thing that’s critical – and sounds like common sense but is not taken into account in the policy framework – is really listening to people who are living with addiction and getting their sense of what’s most likely to be effective,” she says.

Society tends to look at drug addiction as a single issue, when in fact it can be just one factor in a host of life problems. Benefit amounts are “unliveable”, and Lawler says in all cases of addiction, lack of housing should be addressed first, without preconditions of access such as abstinence. Ideally, housing would be given within days and then choice and flexibility offered in support. Addressing drug use can come later and should focus on asking the person what they need.

“What do you need to have opportunities to contribute to the community? Which, in our experience, people want to do. How does a service come to them and understand the complexity of their lives and what they’re dealing with, rather than expecting that person to fit into a system not geared to deal with complexities.

“Sometimes that is construed as people turning a blind eye or somehow being complicit in people’s substance use, and that’s absolutely not what it’s about. It’s about understanding what’s most likely to be effective and doing that.”

It’s also important to give people access to community-based mental health and addiction services that can help them in their home rather than require them to move somewhere else.

“Providing support before someone is really acute is really important,” she says. “Lots of people start using cheap substances available to them, self-medicating because they can’t access the mental health support they really need.”

She says those services are rationed because they’re so poorly funded, and the people Lifewise helps are very quickly excluded from them.

“That’s because they often present as unwell, non-compliant, confused. They are quite quickly either excluded or trespassed, and they just fall off the list. That’s a rights issue in terms of their right to access appropriate care.

“In some ways, it’s the same services we have now. They’re just incredibly poorly resourced and, as a result, very sharply targeted. We need to resource what we know already works well so that it can do more.”

She says, ultimately, a governmental War on Drugs approach will fail, as it has in the past.

“I think the debate about the drug is how we use legislation to prevent people selling it or using it. Though I really understand why people want to stop something so heinous, there is very little evidence that you can legislate drug use out of communities,” she says.

In fact, she doesn’t know a single country that has been able to do that.

“Except where countries have been bold enough to manage supply themselves as governments.”

New Zealand should at least be closely observing those processes and what they achieve, she says.

David Clark speaking during an interview - Health Minister David Clark is awaiting advice on what practical steps the government can take. Photo credit: Mark Mitchell for the NZ Herald.

In Auckland, where the synthetic cannabis problem is very keenly felt, one community response has been the A @ W Collective Impact Initiative, which is focused on improving educational outcomes for young people in West Auckland, including reducing the barriers to education for the community’s most at-risk young people.

In mid-July 2017, the team held a communication day to discuss the increased use and impact of synthetic drugs on young people in the community.

Establishment and Development Manager Janette Searle says one of the challenges faced by the community, particularly the Police, is the impact of policy, laws and regulations on synthetic drugs.

“At the moment, [they] limit what they can do from a Police and legal perspective. This means suppliers are still on our streets, and while they are there, we will always have an issue.”

A @ W is working to connect people in synthetic cannabis hotspots around the country to share learning, knowledge and resources to help everyone address the problem, and Searle says a cross-sector response at all levels is needed for real change. That includes local and national government as well as grassroots community responses.

“That’s what we’re trying to do in West Auckland,” she says.

“Work more collaboratively to support each other and strengthen the work we’re all doing and then work collectively to address the gaps we have in supports, services, information and resources.”

She says the government’s responsibility is to ensure policy and regulation supports the elimination of the drug from communities and reduces its harm.

“That role of enabling also extends to their ability to enable those working in the community to address the challenges and drivers that contribute to drug and alcohol use.”

Sometimes that means additional funding, but more often it’s providing the flexibility in contracts and funding to respond to the needs of the community in the way that best suits it. It also means ensuring practice and policy match.

“Government also has a responsibility to ensure it includes this as a focus across its whole,” she says.

“This needs input and action not just from Justice and Health, but housing, education and youth development, the Ministry of Social Development, Oranga Tamariki and the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment.

“Real change will only happen when they are working together as effectively as possible – which means moving beyond silos, communicating both ways more openly and then supporting each other to do the work.”

She echoes other voices in saying synthetic cannabis is a health, social, cultural, economic and justice issue all at once, which is what makes it such a difficult problem to tackle.

“That is why we’ve included all those sectors into the working groups we’ve established to try and address the issue in our community,” she says.

“By ‘cultural issue’, I don’t mean ethnicity, but rather the culture that has developed within parts of communities that normalises drug use.”

For example, one experience A @ W noticed was that some young people had an uncaring response to those who used the drug and then collapsed. They called them “weak” and “not able to take it”, walking off rather than helping.

“So we’ve been trying to focus some of our key messaging around looking out for your mates and how to care in both acute and general situations,” Searle says.

“That won’t fix it totally, but it’s a start.”

Recent news

Beyond the bottle: Paddy, Guyon, and Lotta on life after alcohol

Well-known NZers share what it's like to live without alcohol in a culture that celebrates it at every turn

Funding boost and significant shift needed for health-based approach to drugs

A new paper sets out the Drug Foundation's vision for a health-based approach to drug harm

Expert Pharmac committee recommends funding for overdose reversal nasal spray

The expert committee has said funding for naloxone in the community should be a high priority