If it’s not true to label, then what are people taking?

With the summer festival circuit over for another year, some people will be looking back on a close shave they had as a result of using drugs. People are taking substances that are not what they expected, with alarming results. Russell Brown investigates what can be done about this.

In late 2011, the year-long Operation Ark reached its climax when Police executed 40 search warrants, arrested 22 people and seized $20 million in assets – shutting down an enterprise they believed had been producing as much as 90 percent of the dance pills in circulation in New Zealand.

Although most news reports referred to the pills as “ecstasy”, the enterprise specialised in pressing and selling analogues of controlled drugs, including the methcathinones methedrone and mephedrone, which are often sold as MDMA, or ecstasy. Officers found eight pill presses in three Auckland locations and $800,000 in cash in a wardrobe and tracked millions of dollars in foreign transactions.

The key figures in the syndicate were convicted last year, but some of those charged will not be tried until 2016, such was the scale and complexity of the case. Did this huge operation put a stop to the illicit pill market? No. While the process drags on, the market has already filled the gap. But it’s not the market it was three years ago.

For a start, MDMA has made a comeback in what seems to be a reflection of trends in Europe. Doses per pill there have risen sharply since, according to a report in Mixmag, a German chemist devised a way of manufacturing MDMA without its tightly controlled precursor chemical PMK.

The ESR drug trends reports from November 2013 to September 2014 depict a multi-coloured array of pills referred to the agency by Police and Customs, the majority of which contained MDMA – the chemical users generally believe they are buying in a pill.

But the market has changed in a more profound way. There may no longer be an Operation Ark-style millionaire running a factory and a distribution network.

While methamphetamine and its precursor pseudoephedrine still seem to be the preserve of criminal gangs, Customs reported recently that there was a “steady” flow of other substances entering the country in small quantities through the postal system. They are often being ordered via the “dark web” and sometimes paid for in bitcoin.

“We accept that a large number of people importing over the internet are importing for their own personal use, and that is without question,” Bruce Berry, Customs Manager of Cargo Operations, told the New Zealand Herald, warning that such importation was still an offence. The result is a flatter market with multiple sources and smaller distribution networks. But what, exactly, is coming in?

Matters of Substance visited ESR’s drug-testing lab to get a better idea of the post-Operation Ark landscape – and to test a pill obtained recently in Auckland (see sidebar).

Senior forensic scientist Jenny Sibley talked us through what they had found in some of the tablets or capsules tested by ESR in the past nine months.

One surprise is that BZP and TFMPP, the ingredients of the once-legal ‘party pills’, are still turning up. Sibley says the level is about 60 percent of that when BZP and other piperazines were banned in March 2008. On the other hand, mephedrone and methedrone have largely disappeared since Operation Ark was brought to heel. The largest group of pills contained either MDMA or bk-MDMA (aka methylone, which was sold for some time by Matt Bowden’s Stargate company under some question of its legal status). Other results were more unusual – and even alarming.

A purple tablet and a green tablet, both marked with heart logos, contained MDPV, the chemical often popularly referred to as ‘bath salts’, and the green one also contained the other ‘bath salts’ chemical alpha-PVP. Both contained ingredients provisionally identified as unknown synthetic cannabinoids – but something ESR later explained is most likely to be an analogue of methcathinone – which continue to flow into the country. It was a particularly unpredictable and risky mix.

Several pills, all with a Mercedes logo, contained dextromethorphan, which is used in some cough suppressants and has sedative and disassociative properties. One, puzzlingly, contained only the antihistamine drug chlorpheniramine. One, a “pale violet-blue tablet” marked with an X, contained the risky 25i-NBOMe.

Although dosage is a crucial issue with some of these chemicals – the NBOMe group in particular – ESR’s systems are not routinely set up to measure purity. But ESR’s ability to verify the contents of a tablet is still streets ahead of that of users – or the people who have to deal with users who have taken the wrong thing.

But the market has changed in a more profound way. There may no longer be an Operation Ark-style millionaire running a factory and a distribution network.

Matters of Substance has been provided with the results of tests discreetly taken at a New Zealand festival last summer. The testers had no access to gas chromatography-mass spectometry (GC-MS) equipment like that used by ESR so used two different reagent tests – Marquis (which is used as a preliminary indicative test by ESR) and Mandelin.

The results from 48 samples tested pointed towards one overwhelming conclusion – most users were not taking what they believed they were.

The most worrying area was around LSD. Only three of 15 samples presented as LSD tested positive as LSD (all were blotting-paper ‘tabs’). Of the remainder (three sugar cubes, 11 tabs and one vial containing liquid), two were the LSD analogue ALD-52 and the remainder were either inconclusive or contained 25i-NBOMe.

Samples presented as MDMA fared no better. Of 23 tested, only four showed positive for MDMA, MDA or MDE (the test kits cannot distinguish between MDMA and the two analogues). All four were in white powder or crystal form. A further nine crystal samples presented in the belief they were MDMA tested negative. By contrast, all crystal samples presented to ESR as MDMA in the past year have been found to contain MDMA.

More than half the pills were found principally to contain amphetamine or methamphetamine. Three pills contained methylone, and one tested positive for 2C-T, a chemical that can be toxic and even fatal in combination with other drugs such as alcohol, ecstasy or cocaine. One was provisionally identified as containing PMA/PMMA, which has been linked to a string of deaths over the past decade. (Jenny Sibley says the ESR drug lab has seen PMA only once in the past 15 years.)

One unlucky punter had paid hundreds of dollars for “cocaine” that turned out to be methylphenidate, or Ritalin.

“Many of the people were very surprised to discover their substance was not what they thought it was,” the testing team told Matters of Substance.

“On several occasions, people made statements such as, ‘I know this is MDMA, I’ve tried it already’, only to find that they had been consuming methamphetamine or methylone instead. This raises questions about the trust relationships that are an innate part of drug-taking culture that are formed around the clandestine nature of the activity. About half of the people whose substances tested negative said they would choose not to take it, with the balance being willing to take the risk.”

The team says that festival management “was willing to allow [testing] to take place but unwilling to be directly involved”, because of concerns about reputational and legal risks, as well as “economic risk”, largely around insurance. “Thus, festivals in New Zealand have strong disincentives to provide harm reduction services.”

On the other side, there is the security risk. Matters of Substance spoke to ‘Jamie’, an experienced dance party promoter who reported a recent trend to severe violent incidents.

“We’ve had issues with overdosing and people having problems with drugs before, but mostly it’s their own problem – they’re fucking their own life up. But what we’re noticing with these ones is really violent outward behaviour. So rather than just dealing with a kid who’s had a bit too much and just sitting with him or shipping him off to hospital, we’re having to deal with kids who are being really, really violent. And it’s difficult to keep them safe and keep everyone else safe.”

The most recent incident seems to have involved NBOMe drugs taken in the belief they were LSD.

“Two kids turned up at the gate displaying full psychotic behaviour, really violent. One of the kids was trying to help people whose eyes were coming out of their heads – he was trying to help them by ripping their eyes out of their heads,” Jamie said.

“These kids were like, ‘We bought this acid from these guys’. I’ve been around the party scene for a long time, seen good and bad trips – and that was not acid.

“There are two key things here. One of them would be being able to identify what people have got – and say, hey, actually that’s shit, and you shouldn’t go near it. But it also seems to be a trend that, as each generation of drugs in the world comes out, it gets banned, and then the next one comes out and is even worse.”

So what to do?

The most current information on new psychoactive substances (NPS) tends to come from websites such as Erowid and Drugs Forum. But although their experience reports frequently model risky behaviour with drugs, the psychonauts of Erowid have a crucial advantage over party kids in New Zealand: they generally know exactly what they’re taking and in what dosage.

“The consumer in New Zealand is very naïve,” says Wellington emergency doctor Paul Quigley.

“They understand the concept of E and LSD, these big groups, and they’re very into the iconography of it. So anything you get on blotting paper is LSD, and anything in a pill with a smiley face on it is E. It’s more about the mode of delivery than the actual substance.

“Quite frankly, there’s growing evidence that MDMA is a safe form of intoxication – especially when you compare it to alcohol and so on – but that’s not what you get. You look at the recent hauls in Wellington of alpha-PVP, which is a highly stimulating hallucinogenic. So not only do you hallucinate, but you get the tachycardia and hypertension. That is not an entactogenic effect.

“Even the dealers know this, so they’re mixing things like benzos into these tablets. The high from the amphetamine effect is almost too high, so they try and balance that by putting in a benzodiazepine. Now we’re talking really dangerous, because benzos are addictive – they’re enough of a problem in prescription medicines, let alone the recreational ones.”

David Caldicott, the toxicology expert at Calvary Hospital in Canberra, Australia, argued on the ABC’s 7.30 programme recently that the authorities should permit professional onsite testing at Australian music festivals and dance parties.

“We know for a fact that, when there is a pill-testing programme in place, consumers actually change their behaviour,” Caldicott told the ABC.

“If the result of a test on a pill is something other than what they thought it would be, they frequently elect to abandon taking that pill. And we have the opportunity to let them know and interface with them about how they can moderate their behaviour.”

Although reagent testing provides only an indication of the contents of a pill – it’s better at telling what isn’t there than what is – authorised testing can be more robust. Portable mass spectrometers, linked to databases like those used by ESR, are present in some clubs in Europe.

They understand the concept of E and LSD, these big groups, and they’re very into the iconography of it. So anything you get on blotting paper is LSD, and anything in a pill with a smiley face on it is E. It’s more about the mode of delivery than the actual substance.

Paul Quigley

One such device is used in Britain by Fiona Measham, a professor of criminology at Durham University. Measham was the only person in Britain to issue a prior warning about so-called ‘Superman’ pills that contained PMMA. The Dutch Drugs Information and Monitoring System (DIMS) had broadcast a televised warning about the pills. The British NHS knew about the Dutch alert but chose not to pass it on. Days later, four young men died after taking the pills in Britain.

Quigley says a “risk register” is generally an easier sell to governments.

“If you find that a certain pill contains PMA, you can say on a website ’Don’t buy red Mitsubishis, break your dealer’s legs and run away, PMA kills’. But if you post the information that a certain pill is 100 percent MDMA, you’re indicating it’s probably safe – and at the same time you’re directly condoning pill use. And that makes the powers that be quite nervous.”

Caldicott has also been active in establishing information-sharing networks with his peers to help them identify and treat emergency drug cases. But it’s his brainchild back in Britain that embodies the most radical official approach to curbing drug harm: Wedinos.

The name is an acronym for Welsh Emergency Department Investigation of Novel Substances, reflecting its genesis in a sentinel monitoring system based around hospital emergency departments and founded by Caldicott (‘wedi nos’ also means ‘after dark’ in Welsh).

Last year, the Welsh National Health Service announced funding (£100,000 annually) for an extension of the programme. Drug users can now send samples anonymously to Wedinos – along with a postcode – and the results are published online.

In New Zealand, emergency doctors have not even had a co-ordinated information system to help them deal with what’s coming through the door. That’s finally about to change.

Quigley says that, in about six months, hospitals (initially only those with a coroner’s mortuary) will be able to access and share current drug information directly from ESR and other sources. A separate project is also investigating wastewater analysis – literally testing the effluent from festival portaloos to try and tell what people are taking.

Quigley is emphatic that, in the end “the New Zealand way is the better way”. He means product approval under the Psychoactive Substances Act, and he has little time for the argument that nothing can be approved without animal testing. He wonders whether – had it not been excluded as a controlled drug – MDMA would have been a suitable candidate.

“The reality is that the market will not stand still while someone finds a way to make the Psychoactive Substances Act work. And if we can’t banish the mystery pills New Zealanders keep on buying and taking, we may need better ways to banish the mystery itself.”

Sidebar: A test case

As part of this feature, Matters of Substance obtained a party pill currently in circulation in Auckland and had it tested by ESR. A one-off test like this typically costs $1,000.

The speckled blue pills are thought to contain ingredients imported from Europe as powders and pressed locally before distribution in a relatively small circle around the original importer. Users have been enthusiastic about them, and while most users we spoke to believed the pills to contain MDMA, some also thought there were other ingredients, including ketamine.

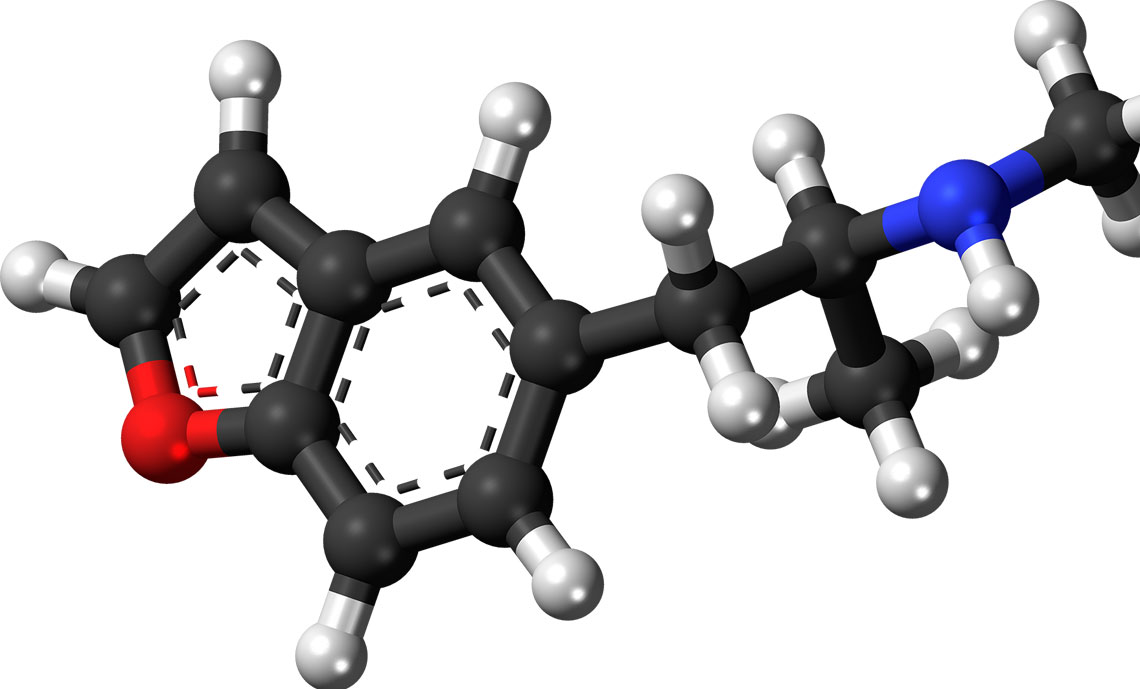

The pills contained no MDMA

ESR did provisionally identify MAPB, which is similar in structure to MDMA, and N-ethyl-APB (EAPB), which is regarded as similar to MDA but is reportedly less potent. The two are said to have slightly different effects. Both are part of the benzofuran group recently outlawed in the UK (where APB had been legally sold as ‘Benzo Fury’), Germany and Sweden but legal in most territories. ESR was unable to determine whether the latter was N-ethyl-5-APB or N-ethyl-6-APB, because it does not have certified reference standards for either substance. In New Zealand, they would be regarded as substantially similar in structure to amphetamine – and therefore Class C controlled drugs under the Misuse of Drugs Act.

Benzofurans have been linked to a number of deaths and acute presentations, almost all in combination with other drugs, and probably in high doses, (internet experience reports suggest that effects become more unpredictable in higher doses and Erowid describes anything over 100mg as a “heavy” dose of 6-APB). Alcohol is considered a potentially risky combination.

ESR also found methoxetamine or MXE, another ‘legal high’ in many territories. It produces a euphoric effect in lower doses, but is considered habit forming and may be risky in combination with benzofurans. It’s a ketamine analogue and is thus a controlled drug analogue in New Zealand.

The other ingredient was 2-fluoromethamphetamine (2-FMA), an amphetamine analogue that has a similar effect to dextroamphetamine. It is therefore also a controlled drug analogue in New Zealand.

Although there have been no local reports of bad experiences on these pills, they do contain substances that are poorly understood in comparison to MDMA and that could react badly with each other in higher doses. It’s a matter of concern that users believe successive generations of the pills have each contained a somewhat different mix. Inevitably, the pills do not come with dosage information.

Photo credit: flickr.com/photos/joshwah

Recent news

Beyond the bottle: Paddy, Guyon, and Lotta on life after alcohol

Well-known NZers share what it's like to live without alcohol in a culture that celebrates it at every turn

Funding boost and significant shift needed for health-based approach to drugs

A new paper sets out the Drug Foundation's vision for a health-based approach to drug harm

Expert Pharmac committee recommends funding for overdose reversal nasal spray

The expert committee has said funding for naloxone in the community should be a high priority