Mythbusters: Ketamine: not just for horses, also for badgers

Ketamine is a short-acting general anaesthetic used for both human medical and veterinary purposes. It is termed a ‘dissociative’, because it impedes the brain’s sensory connection to the body. On 26 February 2008, Associate Health Minister Jim Anderton announced Cabinet had approved the reclassification of ketamine to Class C under the Misuse of Drugs Act to take effect as soon as Parliament approves.

In the meantime, however, media reports about the drug have left it ‘saddled’ with an inaccurate and unhelpful image.

The media’s inevitable power to shape society’s attitudes is a dangerous game, with stereotypes often hidden under the poker-faced mask of balance and objectivity. Journalists will pick up one idea and blindly run with it until something blatantly unavoidable hits them right in the face. Then they will run with the latest revelation until something else hits them. Rarely does there seem time or motivation for them to provide a more complete analysis of drug policy issues.

This has been the case with ketamine aka ‘Special K’. Take, for example, this report from the tabloid The Daily Mirror: “Big Brother star Pete Bennett was a regular user of the horse drug ketamine, his friends revealed last night.”

Or this one by the BBC: “An anaesthetic used by vets as a horse tranquiliser, but becoming increasingly common on Britain’s dance scene, is to be made illegal.”

Or this one by the news agency Reuters: “Scientists have unravelled how a horse tranquiliser and hallucinogenic nightclub drug known as ‘Special K’ can ease depression.”

It is not hard to spot a common theme galloping through all of these reports – horses. A recent Mixmag cover story on ketamine actually pictured a ‘clubber’ wearing a pantomime horse head on the dance floor. It is no wonder then that clubbers and policy makers think of ketamine as something used to sedate our big equine friends.

In a study called It is the most fun you can have for twenty quid (2008), Karenza Moor and Fiona Measham from the University of Lancaster investigated motivations behind ketamine use in Britain. The following comments were made by the participants during the interviews: “It is embarrassing, cos people that don’t understand it are like ‘that is a horse tranquiliser’. It’s like someone starting taking dog worming tablets, why would you do that? Some people are just like ‘why?’”

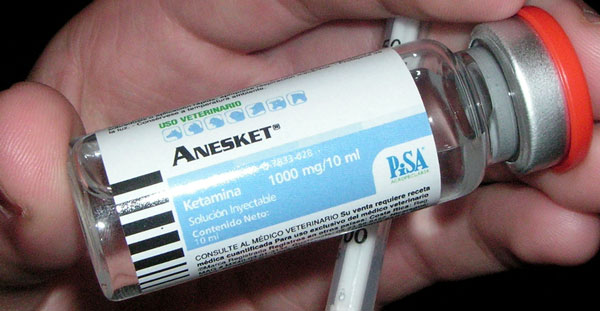

Moor and Measham also came across a clear distinction made by clubbers between ketamine powder viewed as suitable for human consumption, and ketamine in injectable form for veterinary use, and therefore ‘inappropriate for purpose’. “Injecting it would be in liquid form, and that’s for knocking out horses,” says Cassie, a 22-year-old employed ketamine user.

Mythbusters cannot help but wonder why horses, and not guinea pigs, for example, have been receiving so much mention.

The substance is indeed used as an anaesthetic for horses, but it is also widely used as a human anaesthetic. It is used for the elderly, children and in emergencies because it does not suppress the respiratory system, although the powerful hallucinogenic effects – the reason it is used nonmedically – are an unwanted side effect.

Ketamine is used on a whole range of animals, including elephants, camels, gorillas, pigs, sheep, goats, dogs, cats, rabbits, snakes, guinea pigs, birds, gerbils and mice. But why do we never read about the ‘gerbil tranquiliser’ or the ‘bird tranquiliser’? Mythbusters suspects it’s because horses are quite large and the term ‘horse tranquiliser’ provides a more powerful scary drug term for the headline writers than, say, ‘guinea pig tranquiliser’.

Indeed, why does ketamine get the animal treatment at all given that many drugs, including morphine and diazepam, for example, used medically and non-medically on humans, are also used on animals? None of these drugs gets referred to in the context of their animal use as does ketamine. The media never seem to write about the ‘sheep drug diazepam’ or the ‘dog drug morphine’.

While it is hard to find any conclusive answers to these questions, Mythbusters suspects the modern link to ketamine probably stems from mid-90s reports of the drug being stolen from vets and misused. That the drug was a stolen veterinary tranquiliser probably just stuck with journalists. This is despite the fact that, subsequently, most of the drug was supplied to Britain from larger-scale illicit or grey overseas markets.

Obviously, the name filtered through to the New Zealand media in the same way. It is a reflection on the inaccuracies and laziness of drug reporting in the media generally. This sort of misunderstanding is not going to help rational policy development or educating young people about harms or relative risks of drugs.

Mythbusters acknowledges the Transform Drug Policy Foundation's blog from which much information for this piece has been sourced. See www.transform-drugs.blogspot.com.

Recent news

Untreated ADHD leading to addiction and drug harm

A new report shows New Zealand’s failure to adequately diagnose and treat ADHD is likely leading to significant drug harm, including from alcohol and nicotine.

Report: Neurodivergence and substance use

Our latest report pulls together international evidence and local experiences of how neurodivergence impacts drug use

What researchers at University of Auckland are learning from giving people microdoses of LSD

‘Microdosing’ psychedelics involves taking small, repeated doses of a psychedelic drug. Researcher Robin Murphy talks us through the latest Auckland University microdosing study.