Opinion: A nation in denial?

It’s coming on Christmas, and with it, will come the usual increase in alcohol and other substance-induced family violence. Being good Kiwis, though, it’s something we won’t talk about. Nathan Frost, Special Projects Advisor, New Zealand Society on Alcohol and Drug Dependence, turns to a popular children’s folk story that may help us to understand why.

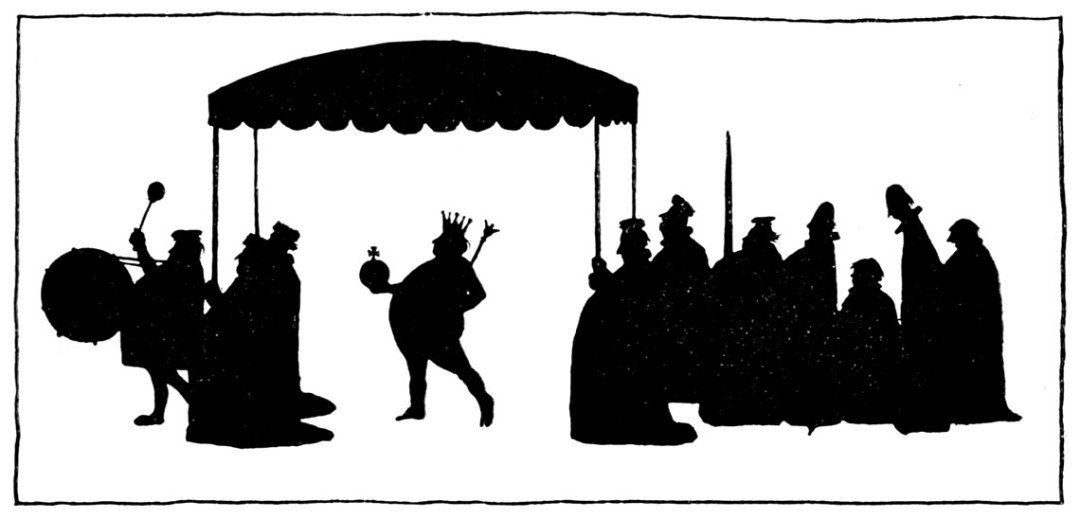

Does anyone remember the Hans Christian Andersen story The Emperor’s New Clothes? It’s about a conceited emperor duped by rogues into donning imaginary clothing and parading naked through town.

As implausible as this plot may seem, Andersen’s skilfully crafted children’s tale explores the very real tension between privately knowing about a problem and not acknowledging the problem publicly.

Its evocative social commentary has huge relevance when examining the collective denial enacted on a daily basis by one in three Kiwis with first- hand knowledge of substance misuse in their families.

Research both here and overseas has shown that family members affected by a loved one’s substance misuse suffer from serious negative impacts on their emotional, physical and social wellbeing.

That’s 1,500,000 Kiwis under significant stress to their physical and mental health and suffering from a decline in the quality of their familial relationships due to fractured communication, loss of trust and ongoing unresolved conflicts.

That’s a huge number of families suffering more incidents of domestic violence, child abuse, financial hardships, employment and legal issues.

At its worst, that’s Kiwi kids growing up in abusive and transient environments, hostages to their parents’ substance misuse issues, with empty bellies at school.

Yet as dire as these problems can be, Kiwis baulk at the idea of airing what are perceived as shameful family substance misuse issues in public.

Andersen’s story helps us understand why this is.

In The Emperor’s New Clothes, two fraudulent weavers tell the vainglorious emperor their fabrics have the magical quality of remaining invisible to anyone extraordinarily simple in character or unfit for the office they hold. The emperor decides he simply must have a suit made from this wondrous material and instructs the rogues to begin immediately.

When the emperor eventually visits the clothing con artists, he sees nothing and thinks to himself, ‘Am I a simpleton, or am I unfit to be an Emperor?’

“Oh the cloth is charming,” he says aloud.

What ensues is a form of fear-induced collective denial. All the townsfolk see that the emperor is naked, but no one has the courage to break the spell until the honesty of a child cuts through the farce.

The Emperor’s New Clothes highlights the vulnerability family members feel when expressing inconvenient truths that challenge established myths they have tacitly agreed to weave around the impact of substance misuse in order to avoid family shame.

Think of the family at the breakfast table the night after a drunken fight has taken place. The mother of the household is wearing sunglasses, but no one makes a comment about why.

Everyone knows what happened, except for the youngest child, but even he knows instinctively not to say anything. If he is like the child in Andersen’s story and blurts something out about the sunglasses, he is immediately met by the family’s wall of silence. He quickly learns to also ignore the elephant sitting at the table.

Kiwis baulk at the idea of airing what are perceived as shameful family substance misuse issues in public.

This is not just a family dynamic, though. At a societal level, New Zealanders struggle to accept the impacts of substance misuse on families.

We all know we have an extremely poor record of domestic violence, particularly with children as victims,

and while we can all agree on the statistics, there seems to be a general inability to accept how commonly alcohol features in this behaviour.

Yet half of all violent crimes committed in New Zealand involve alcohol, including child homicides.

We are extremely quick to talk about the ‘child poverty’ problem in New Zealand but less inclined to examine what impact the purchasing of alcohol, other drugs and cigarettes has upon the family’s finances and, more tellingly, the amount spent on food.

How about the collective denial on display every year as we head into the festive season? Christmas is not far off, and with it comes the winding down of workplaces, the firing up of barbecues and alcohol-fuelled family gatherings.

We know that, as a nation, we drink heavily at this time of the year, and this is reflected in an increased presence of responsible drinking propaganda in the media. Turn the television on, and you’re sure to be informed on a raft of responsible behaviours you can promote around the imbibing of alcohol.

You can be a legend and stop your mate’s drink driving right? Because once they’re dead, you can’t eat their ghost chips, bro!

You can also reason with your loved ones to be responsible in their drinking habits – “No more beersies for you” – or drink “not beersies” (water brewed by clouds). Because according to the propaganda, “It’s not the drinking, it’s how we’re drinking.” Right?

Perhaps that should be replaced with a “Yeah, right!”

I say this because those of us with family members who struggle with addictions to alcohol and other drugs know that, even if we’re not admitting it in public, terms such as moderation and responsibility aren’t really in their vocabularies.

If your family member has a substance misuse issue, no amount of moderation-based alcohol campaigning is going to help you at Christmas dinner when they’re overly pissed and knock their glass of red wine into the potato salad, kicking off a family barney!

By dressing up substance misuse as something it’s not – like it being choice oriented and a matter of moderation and responsibility – we are doing little more than avoiding problems that will not resolve themselves.

So what is the answer?

In all honesty, I don’t really know. But there’s that word – honesty – and I believe a good place to start is by encouraging people to speak the truth.

If Andersen’s story teaches us anything it’s that a child’s truth broke the spell of a collective denial that had spread like a virus and infected the entire town.

I wonder what the truth looks like through the eyes of the many children out there today struggling in familial settings marred by substance misuse. Perhaps we could learn a thing or two from their honest appraisal.

Because no matter what fabric we use to cloak our denial on substance misuse, it will not protect us from the very real consequences it has for families.

RESOURCES

Kina Trust offers support to family members living with loved ones who have alcohol and other drug problems. Visit www.kina.org.nz

Recent news

Beyond the bottle: Paddy, Guyon, and Lotta on life after alcohol

Well-known NZers share what it's like to live without alcohol in a culture that celebrates it at every turn

Funding boost and significant shift needed for health-based approach to drugs

A new paper sets out the Drug Foundation's vision for a health-based approach to drug harm

Expert Pharmac committee recommends funding for overdose reversal nasal spray

The expert committee has said funding for naloxone in the community should be a high priority