Viewpoints: Straight edge: the discipline

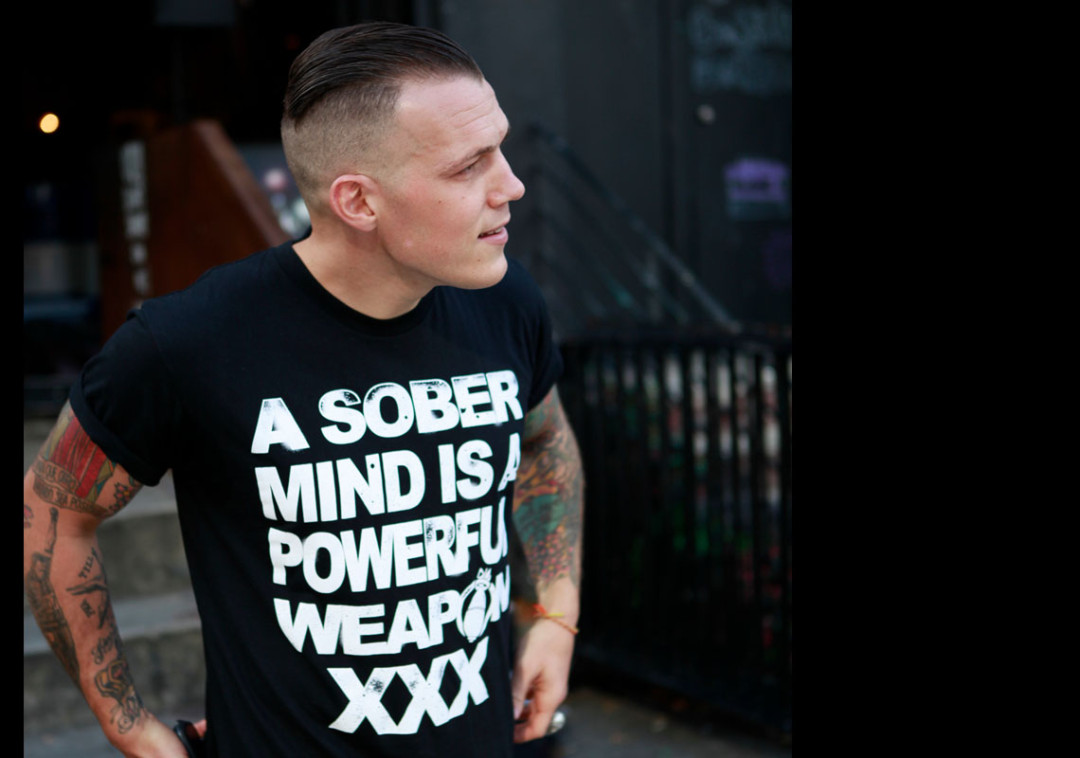

The non-stop rock ’n’ roll party lifestyle often overshadows the music itself. Yet one musical genre explicitly rejects these excesses and offers a haven where drinking and drugs have no place. Richie Hardcore explains what underpins Straight Edge culture and how it’s shaped his life.

The concept of straight edge punched its way into my consciousness during the late 90s, when a little-known band, Culture, screamed at me through cheap speakers. The lyrics – a renouncement of intoxication; of revolution – had me instantly curious.

“Vegan, straight edge, terms that seem stupid to you, but these are terms that separate me from the destruction you refuse to attempt to undo / Renounce all intoxication / My goal is liberation / My goal is revolution.”

At the time, I had just been introduced to the hardcore music scene through which straight edge emerged, and any exploration of straight edge can’t be divorced from hardcore itself.

Hardcore was to become the vehicle to so many of the ideas, beliefs and values that shaped what I do and who I am today. The music is abrasive, aggressive, empowering and visceral, and to a kid like me who was angry at the world, there was an instant connection. Hardcore songs and the culture around the bands took the rage at what I and others saw as unjust in the world and directed it towards something meaningful. It went against pointless, self-destructive or nihilistic behaviour, and it focused young minds towards fighting injustices.

Perhaps more importantly, it made us believe that, by fighting against them, we could actually make a difference. Hardcore bands sang about what they saw to be doing harm in their streets, their communities and the world and encouraged listeners to take a stand. The songs tackled animal cruelty, sexism, materialism, class, and finally, they introduced and embraced straight edge – a lifestyle focused on actively and consciously avoiding intoxication and substance use.

Straight edge became the focal point of what’s become a worldwide community in its own right. While I didn’t officially embrace the straight edge lifestyle until 2007, it’s been a major part of my life since that introduction to Culture as an angstridden teen.

The term ‘straight edge’ was first coined in 1981. In a song Straight Edge that lasted all of 46 seconds, Ian MacKaye – front man for the band Minor Threat – made his declaration to live sober. In so doing, he started a movement that would spread globally. Straight Edge was released alongside another song, Out Of Step, which laid out the simple lifestyle choices he had made to live a connected life:

“Don’t smoke. Don’t drink. Don’t fuck. / At least I can fucking think.”

These things would become the basic tenets of straight edge: avoiding alcohol, other drugs, smoking and, for some, abstaining from promiscuous sex. MacKaye found mainstream American society conformist and oppressive, and he gravitated to the punk scene, with its outlandish fashion and fast music. However, he was soon disillusioned with the binge drinking and endless partying in the punk scene, some of the very things he was seeking to escape. He wanted to be a part of counter culture. He formed Minor Threat, which only released one album and was together for a short period from 1980–1983, but their cultural influence proved huge.

The energy and palpable anger in the music resonated with me. But it was music about something. It wasn’t hedonistic or especially glamorous, and here were older, cool guys, with tattoos and style that supported me not drinking.

Looking at straight edge through my adult eyes – as someone who works in the alcohol drug space – it’s a continual source of frustration that heavy drug and alcohol use is a social norm and a rite of passage for so many. Drinking culture is so ingrained that we need to have dedicated months and movements to encourage a break from the booze such as FebFast, Dry July or Hello Sunday Morning. The organically evolved, youth-led straight edge scene provided, for many, the same haven from the norm as these movements do today.

Personally, my father’s alcoholism was a defining feature of my adolescence, and his struggle made growing up difficult and tumultuous. It gave me an instant aversion to the increasingly heavy drinking and drug use my friends were experimenting with and the problems that started to result. Parties often ended in drunken brawls. Heavy-handed riot Police chased party goers through West Auckland streets. Despite my friends’ hangovers, awkward sexual experiences, fights and run-ins with Police, the binge drinking was never questioned. Yet my decision to mostly say no to alcohol and drugs was one that I had to defend rigorously. The peer pressure to drink was a constant feature of adolescence.

So, when a group of my friends started exploring hardcore and adopting a straight edge lifestyle, it was refreshing. Hardcore was introduced to me by a group of my high school friends who were transitioning away from 70s English punk rock. As a fan of hard rock and heavy metal, the sound they were introducing me to had an instant appeal. The energy and palpable anger in the music resonated with me. But it was music about something. It wasn’t hedonistic or especially glamorous, and here were older, cool guys with tattoos and style who supported me not drinking.

On the few occasions where I would cave to pressure and drink, they would be people to talk to about the embarrassing shit I’d done, and rather than laughing about it and reinforcing or congratulating the behaviour, they would chide me and offer alternative viewpoints. Increasingly I gravitated towards these new sober friends who had built a community around their counter culture music scene.

I didn’t ‘claim edge’ (a term meaning the conscious decision to abstain from all substances as a definitive lifestyle choice) until I was in my mid-20s, but I stayed largely sober throughout adolescence, and these friends helped support that. Before long, I immersed myself in the entire hardcore culture. Both the international and local hardcore scene were vibrant. A do-it-yourself ethic was strong, and kids booked out venues and put on all-ages shows. Trestle tables were pulled out, and fanzines disseminating ideas around straight edge and, of course, music were sold and traded. I joined a band where all the members were straight edge. I played guitar badly, and we booked shows and we released CDs on an independent label in the States. Friends started booking bands from overseas to come and tour New Zealand, and we would drive them around, our small bands supporting our heroes. It was exhilarating!

Straight edge hasn’t been without controversy though. As with any movement, a minority of followers can often adopt its core messages and take them to the extreme. And it’s unfortunate that those isolated examples of intense, and often violent, incidents are the ones that gain the publicity. A small number of followers seized the militancy of some bands and were intolerant of individual choice. People who smoked, drank alcohol or used drugs were judged harshly. Some took this to the absolute extreme, specifically in the United States, and were classified as gangs by law enforcement after incidents of violently confronting drug dealers.

Of course, mainstream media sensationalised these incidents. In 1998, the Los Angeles Times depicted the straight edgers in Utah as “urban terrorists” and described assaults and stabbings at shows, as well as arson and bomb attacks on fast food stores and animal product stores. The straight edgers, the article suggested, “enforce their mantra – True ’Til Death – with brass knuckles, baseball bats, knives, Molotov cocktails and pipe bombs”.

Stories like this did the straight edge scene no favours with public opinion. It was a gross misrepresentation of a movement that, by and large, encouraged young people to be politically engaged and to make conscious and compassionate choices. The straight edge world I encountered was nothing more than communities of like-minded people trying, in their own small ways, to make the world to be a better place. They just chose to do it sober.

My love for the music and its message meant I took my first pilgrimage to New York in 2000 to immerse myself in the hardcore scene. New York at the time was the Mecca of hardcore, home of the legendary club CBGB and countless influential bands. I quickly found a job and spent my weekends travelling to shows with older friends who would introduce me to people who, as a starry eyed 19-year-old, I idolised. One of these was the singer of the band H20, Toby Morse. Toby is a ball of hyperactive energy and enthusiasm, with a contagious lust for life. Through H20, Toby espoused the need to deal with the hardships in life with a clear head and an enduring positive mental attitude. Toby also sang about the need to uplift and support people around you, the benefits of being straight edge and tackling life’s problems head on. Today, while still fronting H20 and touring the world, he also runs a non-profit organisation called One Life One Chance (OLOC). OLOC’s mission is to work with elementary, middle and high school students to engage and inspire them to make healthy choices and live drug-free lives.

Hardcore bands also brought to light other issues. Animal rights, environmentalism, racism, classism and anti-materialism were all common topics of late 90s and early 2000s hardcore. Veganism and vegetarianism were dietary choices that complemented the straight edge lifestyle, and many added meat, dairy and other animal products to the list of things they rejected. The personal was inherently considered political, and often without understanding it, idealistic kids were following Ghandi’s maxim of being the change they wanted to see in the world.

While H20 and other bands espoused straight edge and conscious lifestyle choices in a live and let live approach, other bands were more militant. The foremost of these is Earth Crisis. Formed in 1989, Earth Crisis fused musical influences from metal into hardcore, a pro-animal rights message and environmentalism message alongside staunch straight edge advocacy. The overall effect was a heavier, angrier sound and scene. Their 1993 EP Firestorm soon became an anthem amongst youth tired of the drug-related violence they saw around them.

“Street by street / Block by block / Taking it all back / The youth immersed in poison, turn the tide counter attack / Violence against violence / Let the round ups begin, a firestorm to purify the bane that society drowns in.”

It’s easy to see how such staunch lyrics could be taken to the extreme by those in the community who had a bent towards violence. The band also were avowed vegans, seeing animal liberation and human liberation as intertwined, and they were vocal and public supporters of organisations such as People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA). Thus, Earth Crisis become credited with popularising the term ‘vegan straight edge’. The two things have separate belief and values structures, but given how many straight edge followers have often adopted, at least for a period of their life, a meat-free diet, people outside of the hardcore scene often confuse being straight edge with being vegetarian or vegan as well.

While hardcore, and thus straight edge, in New Zealand peaked in the early 2000s, with very famous American bands such as Hatebreed, Poison the Well and Thursday pulling large crowds at mainstream festivals like the Big Day Out, today, it’s largely dormant, with only a few young fans putting on infrequent DIY shows. That said, many bands around the world continue to play and spread their vision. Both Earth Crisis and H20 continue to write and release new albums, and new bands are constantly emerging. Fans are connected through social media, and there is a strong international online community. These days, I tend to fly to Melbourne when my favourite bands are playing to get a fix of the culture I grew up in.

For more than two decades, I’ve met and bonded with people from all around the world through a shared love of hardcore music and its message – from high fives and stage dives in sweaty clubs in Buenos Aires to festivals in Melbourne, punk shows in Chile and in legendary venues in New York and Boston. Regardless of where I’ve been and whether I’ve been with long-time friends or travelling on my own, hardcore music and straight edge has given me a sense of belonging and community. It’s enabled me to feel at home wherever I am in the world. Long may it continue to do so.

Photo credit: Kaan Hiini, CreativeMornings / AKL

Recent news

Untreated ADHD leading to addiction and drug harm

A new report shows New Zealand’s failure to adequately diagnose and treat ADHD is likely leading to significant drug harm, including from alcohol and nicotine.

Report: Neurodivergence and substance use

Our latest report pulls together international evidence and local experiences of how neurodivergence impacts drug use

What researchers at University of Auckland are learning from giving people microdoses of LSD

‘Microdosing’ psychedelics involves taking small, repeated doses of a psychedelic drug. Researcher Robin Murphy talks us through the latest Auckland University microdosing study.