Strength and harm - the uncertain cannabis equation

Some cannabis is becoming stronger as producers refine their methods and product. How can a legal market manage potency and offer safe consistency to users?

With medicinal cannabis use now legal and the 2020 referendum just over a year away, New Zealand is moving towards a more nuanced understanding of the drug. But it means there are new questions about whether cannabis use can or should be controlled to reduce harm for people who use it.

One of those questions is around regulating potency, which would seem likely to increase if cannabis is legalised in New Zealand and it becomes subject to regular market forces. With 10 US states that have legalised recreational cannabis, 15 that have decriminalised it and 14 that have limited THC content, cannabis products vary widely in potency in the US now, in both their ‘natural’ form and in more processed products.

Generally, when we talk about potent cannabis, we’re talking about the concentration of THC – the compound that gives users their high (and in some cases, intoxication or impairment). Average potency of cannabis products in legal US markets is now triple what it was 20 years ago, and there has been a sharp increase in the potency of the flower in those two decades. A recent analysis of cannabis samples confiscated by the federal Drug Enforcement Administration showed a steady increase in THC content, from 4% to 12% between 1995 and 2014. High-potency cannabis is generally classified as containing more than 10 or 15% THC.

It’s difficult to say what percentages are here. The Institute of Environmental Science and Research (ESR) studied cannabis potency in 1996 and 2010 and found that the latter had THC levels of up to 30%, compared to levels ranging between 1.3 and 9.7% in 1996 – a level that had stayed stable since 1976. But that was comparing one sample from one plant from one grow cycle, compared to those seized by Police. The average was 7 or 8%.

ESR forensic toxicology and pharmaceuticals manager Mary-Jane McCarthy says New Zealand cannabis potency isn’t well researched, and there isn’t a valid dataset that can tell us about THC content in the drug here.

“It’s a really good question and it’s one we need to do some more investigation into,” she says.

THC content in New Zealand cannabis does range enormously depending on whether it’s grown indoors or outdoors.

"All we could say is that it’s an interesting question that needs to be defined further. We haven’t been asked by Police and haven’t done it as a research project in quite a while.”

With Police “defocusing” on cannabis and concentrating more on drugs such as methamphetamine, she says the amount of cannabis they have been submitting has dropped.

“Ahead of the cannabis referendum, I think it has some important considerations. Particularly if we are going to set limits on the THC in licensed varieties of cannabis, then we need to know what was circulating in the illicit market.”

We do know that, globally, THC concentrations have been on the rise in the majority of cannabis products. That’s according to Dr Ryan Vandrey, Associate Professor of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at Johns Hopkins Medicine in Baltimore, Maryland. He says an inhalable dried flower product typically has THC concentrations in the 18–24% range, while processed high-THC extracts like wax and shatter could have 70, 80 or 90% THC. A Lancet study said 94% of the drug sold on the streets of London had a THC content of 14%.

If legalisation goes ahead, it’s not a stretch to see the markets opening up to offer such variation here, too. But it’s a concern, because a recent study says high-potency cannabis products are implicated in faster onset of cannabis use disorder – what we can also call addiction. Symptoms include cravings, withdrawal, lack of control and negative effects on a person’s life. The study, published in the journal Drug and Alcohol Dependence, found young people who started using cannabis in years when the average national potency was higher were more likely to go on to develop one or more symptoms of cannabis use disorder within a year of use. However, the average national potency wasn’t linked to regular cannabis use or transition to daily use.

Studio shot of Beatriz Carlini - Dr Beatriz Carlini, Alcohol & Drug Abuse Institute, University of Washington. Photo credit: University of Washington

The parallel in alcohol is that spirits are more potent than wine, and wine is more potent than beer. But if packaged and labelled appropriately, people understand that you don’t pour a pint of vodka into your glass. You pour a little or mix it, and you can roughly gauge how many standard drinks you’ve had so you don’t get sick or pass out. Loosely, you’re dosing, or titrating, yourself with alcohol.

So, what will happen in New Zealand if personal use is legalised? Do we need some sort of regulation around what makes up a ‘standard smoke’? And if high-potency cannabis can be compared to drinking neat vodka, what does it mean for the user’s health? If you use high-potency cannabis, you increase the risks that you will have a psychotic crisis, says Beatriz Carlini, a senior research scientist at the University of Washington’s Alcohol & Drug Abuse Institute.

The probability of having a psychotic episode or panic attack when you use marijuana is relatively rare, but if it is high potency, it’s more common – and if you legalise it, it becomes more common.”

“More people are using it so there are more chances for that episode. You are seeing that here; there are more people in acute episodes. They might be calling the poison centre, emergency calls, they’re going to emergency rooms with the same kind of symptoms. So this is something that is happening here, and it’s relatively rare, but with the potency increasing, it’s happening more and more.”

Researchers in a Lancet Psychiatry study estimate one in 10 new cases of psychosis may be associated with strong cannabis, based on their study of 11 European cities and towns and one region of Brazil. Daily use of any cannabis makes psychosis more likely, but the study is not definitive proof of harm.

The concerns from a health perspective are twofold, Vandrey says. A single acute dose can make people very uncomfortable or provoke an acute anxiety or panic attack or even an acute psychosis episode.

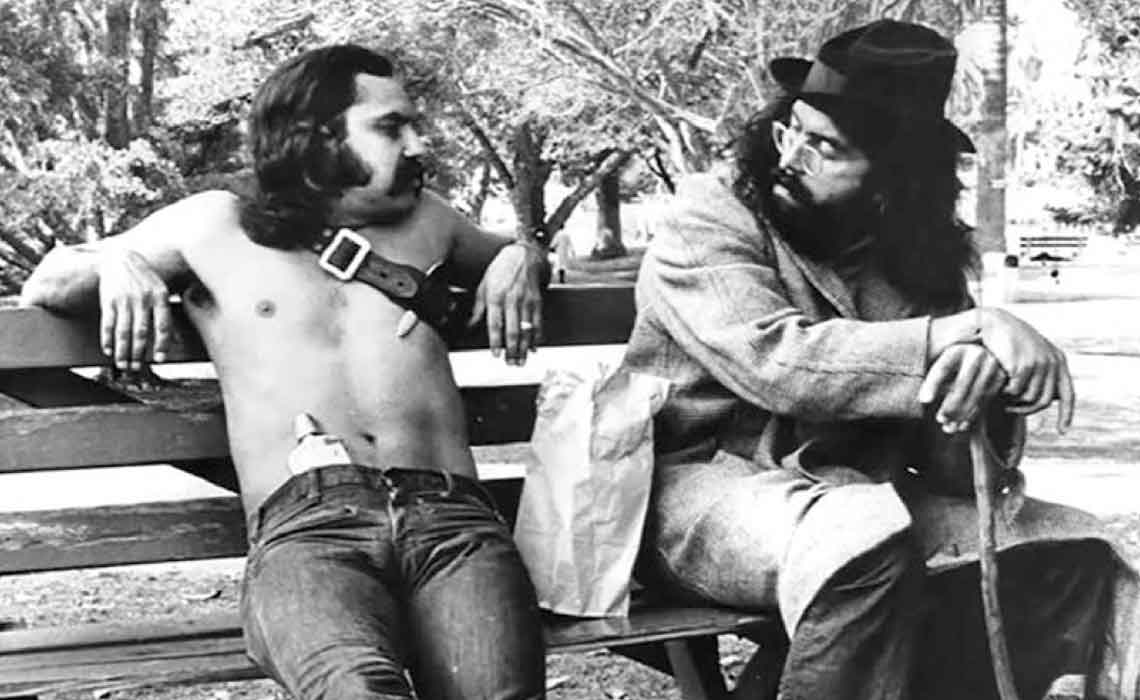

Old black and white photo from the 1970s depicts Cheech and Chong sitting on a park bench. Cheech is shirtless, and has a large joint tucked into a belt which he wears across his chest and shoulder. - In Cheech and Chong’s heyday, joints were oversized but less potent than those rolled today. Photo credit: Cannabis Culture, flickr.com

“THC can have a substantial impact on your heart rate and heart functioning, so people at risk for cardiovascular events should avoid high doses of THC. From an acute drug effect perspective, you can also get impaired, so your ability to drive a car and operate and function can be impacted negatively.”

From a long-term chronic use perspective, the science is clear that some people who start using cannabis develop problems relating to it, building up a tolerance and making it tough to quit. “And the prognosis for people going into formal treatment to quit is not very good unfortunately,” he says. “So, it needs to be recognised as a drug of abuse and treated as something that can cause those kinds of long-term problems as well as short-term problems.”

The risk factors for developing both acute and chronic problems with cannabis are co-occurring mental health problems, using cannabis to cope with problems and heavy daily use. In terms of the acute effects, people with a family history of schizophrenia or other forms of psychosis are at a higher risk of having acute psychosis-like symptoms as a result of cannabis, and it’s associated with an early onset of schizophrenia.

“Adolescent use is typically not recommended due to developmental harms, and then individuals with cardiovascular disease need to be very careful,” he says. “Now all of that being said, that’s within the context of using high-THC cannabis products, and we can’t yet generalise that to other types of cannabis products, of which there are many.”

He says it’s important to remember, when talking about potency, that it doesn’t equal dose – it’s just the concentration of a particular compound in a cannabis product, like the alcohol in vodka compared to beer. “The dose is how much of that you take.”

“If you’re inhaling the drugs, one inhalation of a product with 80 or 90% THC may be too high of a dose for a novice user, whereas a lower potency product would allow the individual to titrate total dose across multiple inhalations.”

Cannabis products that have very high potency tend to be used by people who use cannabis multiple times a day, every day, he says. “They tend not to be novice users. If you have a novice user use a high dose of THC, unwanted and potentially severe adverse effects are possible if not likely. That’s a major concern.

If you evaluate people who use higher-potency products, they tend to have more problems related to their cannabis use.

"What we don’t know yet is whether that’s because of the THC concentrations or if it’s because high-THC concentrated products are marketed towards those people who have extreme use patterns. There haven’t been any really nicely controlled studies that have been able to tease that apart.

“I think we need more research in that area, but from a general perspective, there is no reason to believe that a high concentration of THC in something makes it more dangerous if you can use the same amount of THC in a less-concentrated form – it’s still the same amount of THC,” he says.

“Where there is concern is if you increase the potency in a cannabis product to a point where a person cannot titrate their dose.”

But to know that for sure, you need reliable regulation of dose and knowledge of its effects.

Vandrey believes one answer, if legalisation goes ahead, is public education about cannabis products that steer novice or infrequent users away from those that deliver very high THC doses.

“It’s comparable to telling the person who is starting to be able to drink alcohol to not go straight to [95% alcohol] Everclear, start with a beer. We need some of that with cannabis as legalisation rolls out to prevent people from unintentionally consuming too much.”

Other “really important” factors in policy are ensuring quality control in manufacturing, packaging and labelling so the finished product should be as consistent and reliable as possible to best inform the consumer.

Then there’s creating an understanding of and establishment of unit doses. “What’s an acceptable amount for somebody to consume that you can keep track of and that makes sense for the novice user so you keep them from getting into too much trouble?”

Also needed are assessments to identify people who are potentially getting into problematic use patterns. “There should be cannabis misuse prevention programmes and a pathway to evidence-based treatment options for those who need them.”

Other ideas include putting a cap on the concentration of THC allowed in a product – controlling the unit dose allowed in various delivery forms of products so that concentration can vary but the maximum dose that can be delivered would be standardised.

This means that x number of mg, however it’s taken, is one dose – just like paracetamol. People can take however many doses they need to get their desired drug effect, which should be reliable and reproducible.

Currently, scientists have little understanding of the impact of these high-strength products, says Stanford’s Esther Ting Memorial Professor Keith Humphreys, a former White House drug policy adviser.

His advice for government is to consider regulating and taxing THC content.

“In general, more potent drugs are more addictive and dangerous than less potent ones, so any legalising country would be wise to take steps to limit potency, just as is done with alcohol,” he says. “One possibility is to cap potency outright, and another is to have a surtax on products of higher potency to encourage lower-potency products in the market.”

For users, he says they need to simply be aware that, yes, the product is a drug. “It is a myth that it cannot be harmful.”

Admittedly, we are a long way away from having cannabis packaged, marketed and sold in individual 2.5mg-dose blister packs in the supermarket. Across the world, the drug is often being legalised ahead of policy and potency regulation and ahead of the science that would be valuable in informing policy. So, there is some catching up to do.

“There needs to be some kind of investment in research that can help steer policy,” Vandrey says. “In most cases, legalisation isn’t waiting for all of that science, but it doesn’t mean it shouldn’t be done. You can always do the research and then modify policy and regulation after the fact.”

- Main image credit: Photo: Andres Rodriguez - flickr.com

Recent news

Untreated ADHD leading to addiction and drug harm

A new report shows New Zealand’s failure to adequately diagnose and treat ADHD is likely leading to significant drug harm, including from alcohol and nicotine.

Report: Neurodivergence and substance use

Our latest report pulls together international evidence and local experiences of how neurodivergence impacts drug use

What researchers at University of Auckland are learning from giving people microdoses of LSD

‘Microdosing’ psychedelics involves taking small, repeated doses of a psychedelic drug. Researcher Robin Murphy talks us through the latest Auckland University microdosing study.