What can we learn from the psychedelic renaissance?

Research into the therapeutic use of psychedelics, stymied by War on Drugs thinking in the 60s, is enjoying a significant comeback, thanks to recent studies about their efficacy for treating addiction and mental illness. But how might these drugs be used in a real-world situation, and what are the implications for recreational users? Max Daly reports.

In 1967, after the release of the Beatles’ album Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, Paul McCartney became the first British pop star to admit taking LSD.

“It opened my eyes,” he told fashion magazine Queen at the time.

“We only use one-tenth of our brain. Just think of what we could accomplish if we could only tap that hidden part. It would mean a whole new world, if the politicians would take LSD, there wouldn’t be any more war or poverty or famine.”

The rest is history, because McCartney’s hippy dream was swiftly suffocated. Amid rising 1960s recreational drug use, the authorities got paranoid and clamped down on the blossoming world of psychedelic science and culture. A huge body of promising research into the medical uses of these drugs was mothballed, and the drugs were reconfigured as an undesirable social poison or, in President Lyndon B Johnson’s words in his 1968 State of the Union address, “a threat to our nation’s health, vitality and self-respect”. Psychedelics became just another banned high alongside cannabis, cocaine and heroin.

Yet now, after decades of being forsaken by the authorities, psychedelic drugs find themselves ushered in from the cold as potential saviours in the battle to address spiralling global depression and entrenched addiction.

For many scientists and drug researchers, the core idea that psychedelics may be clinically useful is not new. Research into the use of LSD in treating mental illnesses and alcoholism dates back to around 1950, 12 years after Swiss scientist Albert Hofmann first synthesised the drug.

A huge number of studies of varying degrees of quality and ethics were conducted, so much so that, by 1958, scientists were writing literature reviews on the existing research into LSD for psychotherapy treatments. Many of the trials showed promise – an early convert was Bill Wilson, the co-founder of Alcoholics Anonymous – although some of the them were questionable. LSD was tested on children as a cure for autism and given to soldiers as part of mind control experiments conducted by the British secret intelligence service MI6.

Despite some of the more extreme research carried out and allegations of pro-LSD bias levelled against some clinicians, the research was nevertheless ground-breaking. By the mid-1960s, more than 40,000 patients had been administered LSD as part of their psychiatric treatment, and psychedelic research had produced more than 1,000 scientific papers.

Psychadelic Science 2017 - After being suppressed for decades, research into psychedelics is making a comeback.

Of course, in the 1960s and 1970s, psychedelic drugs were not just about white coats – they were about having a good time. When the recreational use of LSD and magic mushrooms began to grow in the US and in Europe – and these drugs became synonymous with rebellion and counter culture – the authorities banned them and shut the gates on scientific research. By the end of the 1960s, studies were severely curtailed, although on the other side of the Iron Curtain in the Soviet-controlled Czechoslovak Socialist Republic, research at five centres for psychedelic research continued until the mid-70s.

Fast forward to 2018, and the ability of psychedelic drugs to treat depression, addiction and trauma is again being measured along with their effects on the human brain, but this time under modern scientific conditions. As a scientific area of investigation, psychedelics are snowballing.

Ecstasy, the banned psychedelic stimulant used as a therapy tool in the late 1970s before sparking a revolution in dance and club culture a decade later, could become a legal medicine for the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) by 2021. Psilocybin, the active ingredient in illegal magic mushrooms, is showing promise for the treatment of depression, addiction to nicotine and alcohol and in reducing anxiety in people with cancer.

Meanwhile, ketamine, the hallucinogenic anaesthetic that gives users the power to become – according to 1970s K-hole explorer John C Lilly – “peeping toms at the keyhole of eternity”, is being trialled as a treatment for heavy drinking and as a rapid-acting alternative to pills such as Prozac for treating depression. There has also been research into the use of ayahuasca, a hallucinogenic brew containing DMT used by indigenous people in Amazonia, for depression.

In many of the studies, psychedelics are proving effective in situations where conventional treatments have failed. It is likely this is because of their ability to ‘unlock’ the human mind. Scientists have shown that taking psychedelic drugs can reroute the way the brain talks to itself by bypassing its default mode network. Taking psychedelic drugs can temporarily switch the brain off autopilot by connecting parts that do not usually communicate with each other, enabling people to overcome entrenched perceptions and to see things from a fresh perspective.

“What we see under psilocybin and other psychedelics is an ability to step back, like an astronaut who goes up into space,” explains Dr Robin Carhart-Harris, Head of Psychedelic Research at Imperial College London, in a promotional video for Compass Pathways, a British start-up that is preparing an extensive trial for treating 400 patients who have treatment-resistant depression with psilocybin.

“All of a sudden, you can see the whole of the Earth. It allows the mind and the brain to operate in a more expansive way.”

Psilocybin, the active ingredient in illegal magic mushrooms, is showing promise for the treatment of depression, addiction to nicotine and alcohol and in reducing anxiety in people with cancer.

Psychedelics are not being used as a magic bullet but as an adjunct to other treatment, such as talking therapy. For example, psilocybin is not stopping smoking in some patients through a biological reaction as other medicines that directly affect nicotine receptors might do. Instead, the drug is being shown to work by shifting patients into periods of deep reflection, then engendering change.

Clinical studies have found LSD can enhance music because of its effects on the brain, and this works both ways – music can influence the way people trip. Magic mushrooms have been found to produce “sustained changes in outlook and even political perspective”, for example, an increased “nature-relatedness and decreased authoritarianism”. Moreover, research is showing that hallucinogens are way less likely to cause long-term mental damage – and far less than other drugs – than the fear-mongering has suggested.

So what has prompted this renaissance? Brad Burge is Director of Communications at California-based Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS), founded by Rick Doblin in 1986. Alongside the Heffter Research Institute in Zurich and the UK-based psychedelic research funding group the Beckley Foundation, MAPS has driven what Burge describes as an “unprecedented” rise in psychedelic research in the last 15 years.

“It is the work of a widespread, international network of scientists, doctors, therapists and patients who want to see better treatments developed for a variety of mental illnesses.”

This has occurred, Burge says, within the context of “declining public confidence in currently available pharmaceutical treatments for PTSD, anxiety, addiction and other mental illnesses” as well as the “failed War on Drugs, which uniformly categorises all psychedelics as drugs of abuse despite scientific evidence to the contrary”.

As with the burgeoning legal cannabis industry in America, money men are becoming increasingly attracted to the idea of investing in the potential of psychoactive substances to improve people’s health. Compass Pathways has seed funding from a host of high-profile investors including PayPal founder Peter Thiel for its psilocybin trials. If MAPS is able to conduct its crucial but highly expensive phase three trials of MDMA-assisted psychotherapy for PTSD, it will be down to funding from a New York philanthropist and an anonymous bitcoin millionaire.

It is clear there has been a rebirth in research alongside a fresh willingness by financiers to fund it, but what of psychedelia and the cultural landscape of these drugs? Is this changing too, or is this renaissance all about labs and money?

These days, I increasingly smile at how mainstream psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy is becoming ... It’s profoundly satisfying."

Brad Burge, Director of Communications at California-based Multidisciplinary Association for PsychedThe apparently counter-intuitive story about how ‘mind-bending’ drugs can improve our mental health has become a staple for the mainstream media. They love it. Scare stories about children’s tattoos impregnated with LSD are being replaced by a steady stream of positive articles about the psychological benefits of LSD, ecstasy and magic mushrooms. This is not to say ignorance and stigma has vanished – far from it – but this coverage has improved the image of psychedelics.

“These days, I increasingly smile at how mainstream psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy is becoming,” wrote Doblin in the latest MAPS bulletin.

“It’s profoundly satisfying to see this occurring, about half a century after the backlash to the psychedelic 1960s.”

Prompted by media coverage, the public seems to be warming to the idea of psychedelics as medicines. Last year, a survey by YouGov found nearly two-thirds of American adults said they would be willing to try MDMA, ketamine or psilocybin if it was proven safe to treat a condition they have. Last year’s Psychedelic Science 2017 conference in California attracted 3,000 attendees.

But the rise in scientific, professional and intellectual interest in psychedelics is not reflected in any softening of the law or rise in the recreational use of these drugs. In Britain, while the minor psychedelic ecstasy remains a prevalent drug and ketamine has been added to the menu, the use of LSD and magic mushrooms by both young people and adults has fallen by around two-thirds over the last 20 years. The picture in America is the same.

Compared to most recreational drugs, the use of LSD and magic mushrooms has always been a niche pursuit, largely limited to subcultures and intellectuals, from the hippies and punks of past generations to today’s dark web psychonauts and 21st century new agers. Even during the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s – seen as being the golden age of acid – the drug was only ever popular with a very small proportion of the population.

However, there are signs psychedelic users are becoming more diverse. Micro-dosing of LSD, most notably in Silicon Valley, has been on the rise – a trend that Rosalind Stone, an expert in psychedelics and a director at the harm reduction group Drugs and Me, says “fits very neatly into the changing social perception” of psychedelics.

“People have always taken psychedelics, and they did not stop when the research stopped, but their use goes way beyond the hippy stereotype.”

She points out that the #psychedelicsbecause social activism campaign shows people from all age groups and professions using these drugs for a wide array of therapeutic, recreational and medicinal purposes.

Despite all the publicity and interest, the number of dedicated LSD and magic mushroom users is unlikely to rise, says Rob Dickins from the Psychedelic Press.

“Most people never try them. Even if they do find them fascinating, most will take drugs like LSD only a few times. For me, ‘psychedelic culture’ is just a bunch of wyrd enthusiasts. It’s very unlikely, therefore, we’ll see a sudden and major spark in numbers taking them regularly. The nature of the experiences they elicit precludes this.”

There is a feeling among some psychedelic drug users that the widening distinction between mainstream scientific research and broader cultural use of psychedelics is somehow leaving them behind, while their own use remains a criminal and stigmatised act.

For example, ayahuasca, which has for centuries been used in spiritual ceremonies by indigenous tribes of the Amazon basin, is showing promise in treating depression. However, due to the rise in interest from Western tourists in the drug, indigenous people have seen a steep rise in the cost of the brew and are increasingly likely to be prosecuted over the drug. Constanza Sanchez of the International Center for Ethnobotanical Education, Research & Service says communities in Colombian Amazonia see the appropriation of ayahuasca as being indicative of wider and more pressing threats to their way of life, such as armed conflict and mining companies taking over their land.

Even though scientists are trying to find a way of developing new pills that have the medicinal properties of psychedelics minus the trippy effects, research has shown that the emotional, spiritual side of taking psychedelics is a crucial part of their effectiveness. Severing the mystical side of psychedelics from the science, whether in the lab or in wider society, may prove difficult.

The use of psychedelic drugs for medicinal purposes may be fast approaching. But where will that leave those people who are using the exact same drugs for recreational use? Amanda Feilding is currently working on a report looking into how to regulate psychedelic drugs. One of the options she identifies is based on the cannabis club model, allowing the creation of non-profit collectives that produce and supply psychedelic substances to their members for consumption on site. Yet she can’t envisage any form of regulation any time soon.

It’s refreshing that, in 2018, you are as likely to read about psychedelics in a clinical trial as you are a criminal one. Ultimately, the psychedelic renaissance is a welcome, long-overdue re-examination of how these drugs can be used for the good of mankind. But their utility must be grounded not just in scientific trials but real-world practicality.

“We have countless examples of interventions and therapies that showed great promise in efficacy trials but that failed to deliver in larger trials, or it simply wasn’t feasible to deliver the intervention to scale,” says Harry Sumnall, Professor in Substance Use at the Public Health Institute, John Moores University, Liverpool.

“Outside private practice, for example, we struggle with the funding and delivery of even basic psychosocial therapies for mental health disorders. We need to start thinking about the next steps for utilisation of these therapeutic approaches in universal healthcare systems to see if they’re cost-effective, if they’re acceptable to patients and healthcare professionals or indeed if there is even a role for them in routine healthcare.

“Whether administration of a psychedelic drug can reduce the intake of another drug is largely irrelevant if we haven’t also developed strategies to reduce social and structural stigma, help overcome social isolation or ensure people can get access to decent jobs and homes.”

The people for whom psychedelic drugs will prove most useful – those suffering depression, addiction and trauma – are also society’s most excluded. The focus has to be on how these substances can effectively be used to change the lives of the socially excluded rather than being a bespoke treatment for a select few.

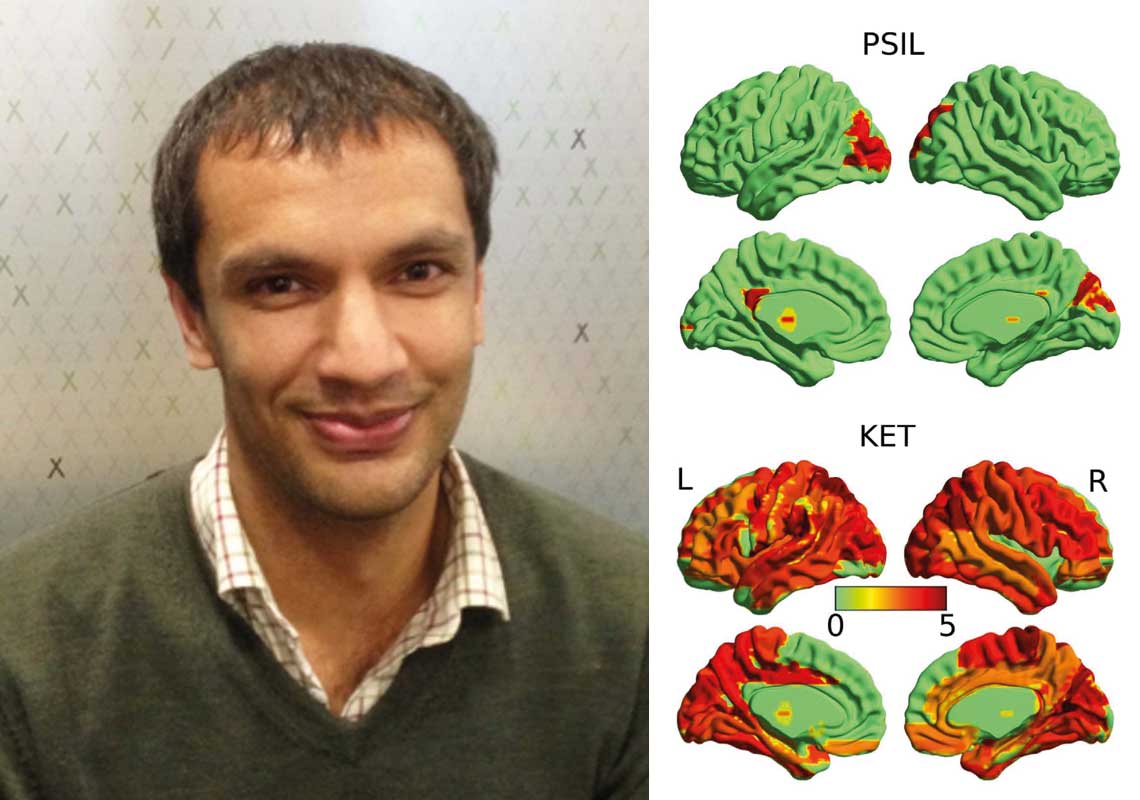

Dr Suresh Muthukumaraswamy is involved in local research into how ketamine and other drugs can alter brain activity.

Local research unlocking new treatment potentials

Additional reporting by Natalie Bould

Communications Adviser, NZ Drug Foundation

In 2016, a kiwi scientist was part of an international research team that released the results of a study into the possible therapeutic benefits of LSD.

At the time the research was carried out, Dr Suresh Muthukumaraswamy was working at Cardiff University’s Brain Research Imaging Centre. The research team got approval to carry out trials on 20 healthy volunteers who had used psychedelic drugs before.

These trials revealed that activity in certain areas of the brain, which are overactive in depression and potentially in addiction, can be altered to create different patterns of communication. This was a breakthrough in the possible therapeutic use of psychedelics.

“The results were very promising,” says Dr Muthukumaraswamy. “But there’s a lot still to be done.”

Dr Muthukumaraswamy returned to NZ on a Rutherford Discovery Fellowship to continue his studies closer to home and family. However, so far it’s proved impossible to secure any funding for local trials of LSD. He says the technique they used, called magnetoencephalography, is very expensive and there are no MEG scanners in New Zealand.

The illicit status of most psychedelics also makes funding difficult to obtain.

These days, Dr Muthukumaraswamy is a senior lecturer and researcher in the Faculty of Medical and Health Sciences at Auckland University. He and his team use brain-scanning techniques to measure both blood flow and electrical activity. The research involves testing how a range of drugs, particularly ketamine, can alter brain activity in both healthy individuals and patient groups.

In 2015, they discovered that fast-acting ketamine (once popular in the clubbing scene, and known colloquially as “Special K”) can be used to treat depression. This research is ongoing; however, the therapeutic potential of ketamine is limited because the effects, while fast acting, are also short-lived.

He says clinical trials of drugs are vital. “For a long time, in psychiatry, what we’ve done is to give a patient drugs, close our eyes and hope it works. And to some extent it has… but not with a good understanding of why and how it works.”

Dr Muthukumaraswamy hopes that with a bit more insight, they can develop new drugs which may be faster acting than conventional antidepressants, but more long-lasting than ketamine.

Recent news

Untreated ADHD leading to addiction and drug harm

A new report shows New Zealand’s failure to adequately diagnose and treat ADHD is likely leading to significant drug harm, including from alcohol and nicotine.

Report: Neurodivergence and substance use

Our latest report pulls together international evidence and local experiences of how neurodivergence impacts drug use

What researchers at University of Auckland are learning from giving people microdoses of LSD

‘Microdosing’ psychedelics involves taking small, repeated doses of a psychedelic drug. Researcher Robin Murphy talks us through the latest Auckland University microdosing study.