Without warning

Unlike some other jurisdictions, New Zealand has little in the way of a drug early warning system for emerging substances and usage trends. Such a tool may well have saved lives in recent times. Rob Zorn summarises the issues and looks at a couple of existing systems we could emulate.

The complete absence of product ingredient listings or labelling of new synthetic drugs being sold on the black market means no one knows exactly what is contained in each product being flogged on street corners. Is the drug in one packet the same as the last? Is potency consistent within a batch? Are any adulterants added? What are the effects? What is a low-risk dose? Knowing the answer to these questions can mean the difference between life and death.

Samples obtained by VICE NZ in Auckland and the Drug Foundation in Wellington, then tested by the Institute of Environmental Science and Research (ESR) in September, show more than one hazardous substance is circulating under the discredited term ‘synthetic cannabis’. Names are important, so while it’s true these new products act on the cannabinoid system in the body, they are hugely different chemicals with very little relation to natural cannabis or early synthetic variations like Kronic.

The two small bags were tested using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. The results for the sample from Auckland show that two identifiable substances had been sprayed on the plant matter. These were pFFP and AMB-FUBINACA (also known as FUB-AMB). The former is a piperazine derivative listed as a class C drug with known psychedelic properties. It is the ultrapotent AMB-FUBINACA that has been linked to drug deaths and life-threatening conditions, both in New Zealand and overseas.

In the Wellington sample, a different chemical was found: synthetic cannabinoid 5F-ADB. This powerful chemical has been linked to deaths in Japan, and hospital admissions for extreme mental tension and anxiety in many countries.

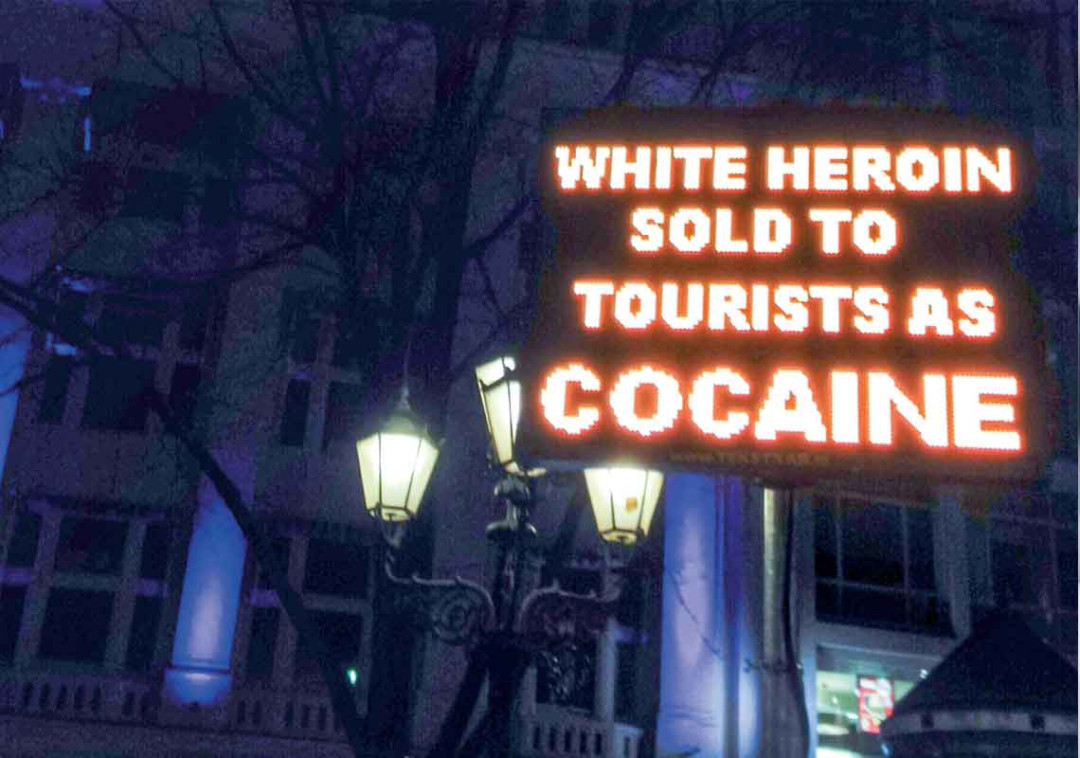

The problem is not only with the smokeable synthetic drugs. Testing carried out by the Drug Foundation and KnowYourStuffNZ at festivals last summer indicated that drugs often contained substances other than what the person thought they were buying.

As manufacture of new psychoactive drugs proliferates and an ever-evolving black market constantly reinvents itself, it’s vital the New Zealand health system is prepared for wave after wave of new and dangerous substances.

Accurate information is crucial for medical professionals and first responders. What substances are in this stuff? How do we treat people who’ve taken it? Getting samples tested by ESR then sharing the information with hospitals and emergency departments needs to happen as fast as possible. And when something highly dangerous is circulating, credible messages need to hit the streets.

The Drug Foundation began calling for a drug early warning system in New Zealand in 2012. An early warning system is designed to detect and publish information about currently circulating drugs so people can make informed decisions before taking them. When a highly dangerous substance is detected, protocols are in place to issue alerts. These can be rapidly and widely shared, to help people avoid anything that is dangerous and save lives.

Perhaps the first thing would be to put a centrally co-ordinated interim process in place where DHBs, Customs, Police and other agencies could at least share what information they do have. That’s not currently happening.

A few jurisdictions around the world are already doing this in various ways – at a relatively high level in Europe and at more popular levels in Wales and Australia (see sidebar).

There is no reason why we couldn’t also do this here. In fact, the National Drug Policy (2015–2020) specifically endorses a multi-agency early warning system to “monitor emerging trends and inform both enforcement and harm reduction strategies”. The Ministry of Health has contracted the University of Auckland’s Centre for Addiction Research to investigate what data is currently being gathered that could contribute to an early warning system, and how it could be shared.

That work is already underway, and the next step will be to develop a prototype with intended key players including Customs, Police, emergency services, the Ministry of Health, ESR, Massey University’s SHORE researchers and the Drug Foundation. As reported elsewhere in this issue, without a dedicated budget, progress is likely to be slow (see the cover feature “We should have know”).

Centre for Addiction Research Associate Director David Newcombe believes it is too early to say what such a system might look like. Apparently, we already collect a lot of good data. How to share it is the issue, but he says getting a system like the Welsh WEDINOS (see sidebar) in place here probably isn’t likely in the near future.

Newcombe says it’s really hard to know for sure whether having this system already in place would have helped mitigate the recent epidemic.

“It’s about whether the border control agencies we hope might feed into this system might have picked up that this new synthetic cannabinoid was around. To be honest, we just don’t know what happened to those people because we haven’t seen the forensic pathology.”

So it seems an early warning system for New Zealand remains an urgent but overdue priority. Perhaps the first thing would be to put a centrally co-ordinated interim process in place where, DHBs, Customs, Police and other agencies could at least share what information they do have. That’s not currently happening.

As Drug Foundation Director Ross Bell said in a 26 July media release, “Regrettably, the situation with dangerous substances circulating … is likely to be repeated. We shouldn’t be caught out again.”

Unless we get cracking on an early warning system of our own, we may well be.

Two existing early warning systems

EU Early Warning System

The EU Early Warning System, operated by the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction since 2005, is probably the most comprehensive in existence but works at a relatively high level.

It’s a network of European early warning mechanisms that collect and share information on new drugs, and the products found in member states that contain those drugs.

Each member state has what are called the National Focal Points (NFPs) and Europol National Units (ENUs). NFPs have a public health focus and collect data around trends in drug availability, emergence, usage patterns and addiction. They draw information from a variety of sources, including the media and existing forensic early warning systems.

ENUs have a law enforcement focus and collect data on things like the supply of new psychoactive substances, controlled drugs found in new products and the involvement of organised crime in manufacture or marketing.

Combined, these agencies act as central co-ordination points for a two-way flow of information between individuals and organisations at a national level, and the wider European network.

The benefit of this model is that it connects the wide range of people concerned with these substances, allowing for efficient dissemination of critical information to Police, coroners, Customs, health providers and so on. The data collected is also stored in a searchable database, ensuring that emerging knowledge about new drugs is easily accessible.

Welsh Emerging Drugs and Identification of Novel Substances (WEDINOS)

WEDINOS emerged in 2009 following an increase in emergency department presentations in Wales, where those presenting had taken unknown drugs. A team of clinicians devised an informal mechanism whereby samples of unidentified drugs provided by patients were tested and profiled.

In 2013, Public Health Wales expanded the project to a national framework. It now also collects data on users’ experiences and drug trend information from a wider collection of sentinel monitoring hubs. Information about emerging substances and pragmatic harm-reduction advice are then disseminated to the whole population via its website, media releases, publications and other means. Samples and data can be submitted by any person or organisation in Wales.

Recently, one of the WEDINOS pilot clinicians, Emergency Department Consultant Dr David Caldicott, has replicated the system, known as ACTINOS, in Australia’s Capital Territory.

Recent news

Beyond the bottle: Paddy, Guyon, and Lotta on life after alcohol

Well-known NZers share what it's like to live without alcohol in a culture that celebrates it at every turn

Funding boost and significant shift needed for health-based approach to drugs

A new paper sets out the Drug Foundation's vision for a health-based approach to drug harm

Expert Pharmac committee recommends funding for overdose reversal nasal spray

The expert committee has said funding for naloxone in the community should be a high priority